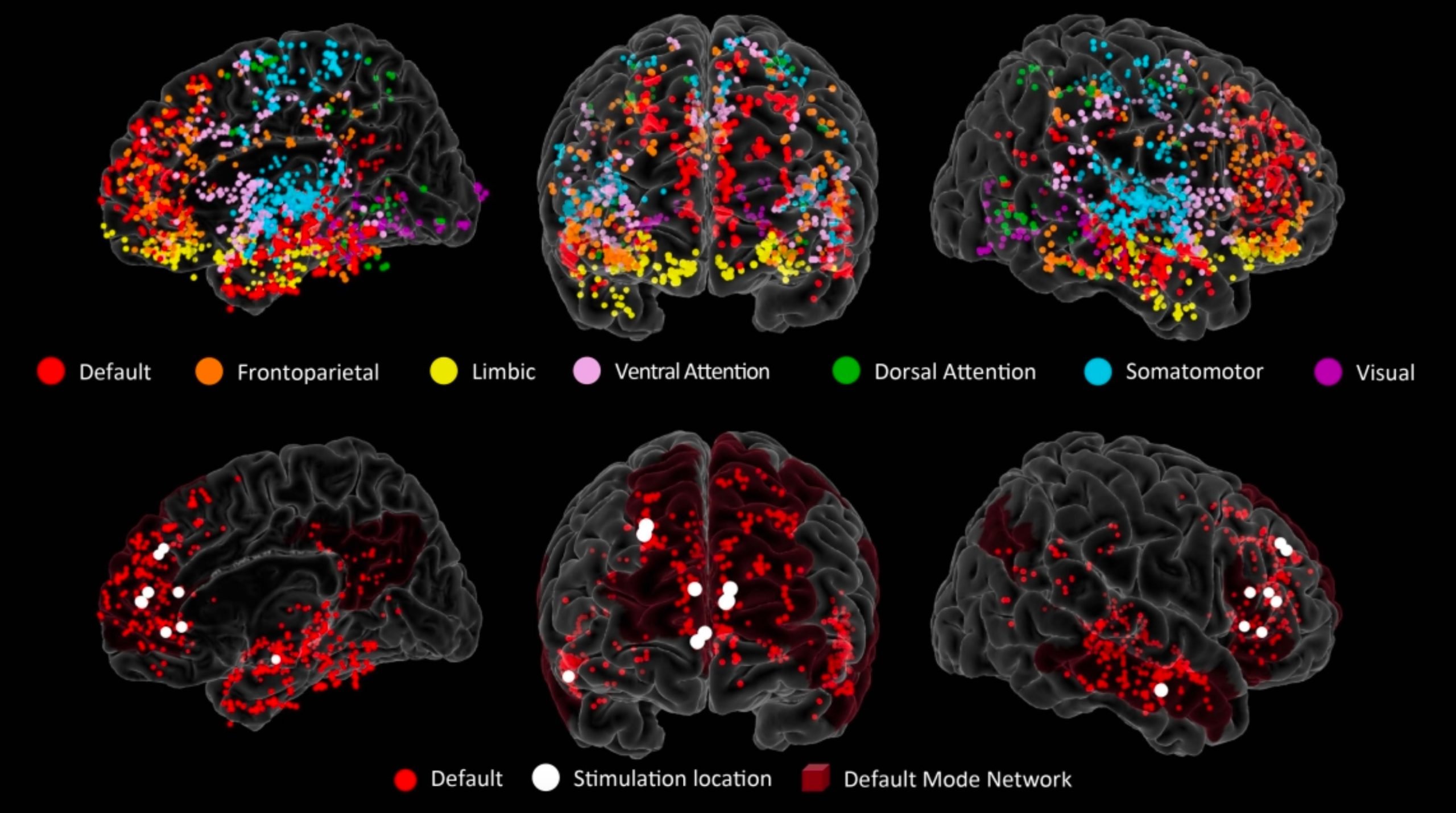

Electrodes at multiple brain regions reveal brain activity in real time. Colored dots show the locations of all of the electrodes across all patients, color-coded by brain region. Red dots in the lower images show the locations of the electrodes in the DMN. Credit: Eleonora Bartoli, Ethan Devara, Huy Q Dang, Rikki Rabinovich, Raissa K Mathura, Adrish Anand, Bailey R Pascuzzi, Joshua Adkinson, Yoed N Kenett, Kelly R Bijanki, Sameer A Sheth, Ben Shofty, Default mode network electrophysiological dynamics and causal role in creative thinking, Brain, 2024;, awae199, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awae199

A collaborative study by researchers from the University of Utah Health and Baylor College of Medicine has uncovered the crucial function of the default mode network in creativity using sophisticated brain imaging, highlighting possibilities for future therapeutic interventions.

Have you ever had the solution for a tough problem suddenly hit you when you’re thinking about something entirely different? Creative thought is a hallmark of humanity, but it’s an ephemeral, almost paradoxical ability, striking unexpectedly when it’s not sought out.

And the neurological source of creativity—what’s going on in our brains when we think outside the box—is similarly elusive.

But now, a research team led by a University of Utah Health researcher and based in Baylor College of Medicine has used a precise method of brain imaging to unveil how different parts of the brain work together in order to produce creative thought.

Their findings were recently published in the journal Brain.

The new results could ultimately help lead to interventions that spark creative thought or aid people who have mental illnesses that disrupt these regions of the brain.

Outside the box

Higher cognitive processes like creativity are especially hard to study. “Unlike motor function or vision, they’re not dependent on one specific location in the brain,” says Ben Shofty, MD, PhD, assistant professor of neurosurgery in the Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine and senior author on the paper. “There’s not a creativity cortex.”

Ben Shofty, MD, PhD. Credit: University of Utah Health

But there’s evidence that creativity is a distinct brain function. Localized brain injury caused by stroke can lead to changes in creative ability—both positive and negative. That discovery suggests that narrowing down the neurological basis of creativity is possible.

Shofty suspected that creative thought might rely strongly on parts of the brain that are also activated during meditation, daydreaming, and other internally focused types of thinking. This network of brain cells is the default mode network (DMN), so called because it’s associated with the “default” patterns of thought that happen in the absence of specific mental tasks. “Unlike most of the functions that we have in the brain, it’s not goal-directed,” Shofty says. “It’s a network that basically operates all the time and maintains our spontaneous stream of consciousness.”

The DMN is spread out across many dispersed brain regions, making it more difficult to track its activity in real-time. The researchers had to use an advanced method of brain activity imaging to understand what the network was doing moment-to-moment during creative thought. In a strategy most commonly used to pinpoint the location of seizures in patients with severe epilepsy, tiny electrodes are implanted in the brain to precisely track the electrical activity of multiple brain regions.

Participants in the study were already undergoing this kind of seizure monitoring, which meant that the research team could also use the electrodes to measure brain activity during creative thinking. This provided a much more detailed picture of the neural basis of creativity than researchers had been able to capture before. “We could see what’s happening within the first few milliseconds of attempting to perform creative thinking,” Shofty says.

Two steps toward originality

The researchers saw that during a creative thinking task in which participants were asked to list novel uses for an everyday item, like a chair or a cup, the DMN lit up with activity first. Then, its activity synchronized with other regions in the brain, including ones involved in complex problem-solving and decision-making. Shofty believes this means that creative ideas originate in the DMN before being evaluated by other regions.

What’s more, the researchers were able to show that parts of the network are required specifically for creative thought. When the researchers used the electrodes to temporarily dampen the activity of particular regions of the DMN, people brainstormed uses for the items they saw that were less creative. Their other brain functions, like mind wandering, remained perfectly normal.

Eleonora Bartoli, PhD, assistant professor of neurosurgery at Baylor College of Medicine and co-first author on the paper, explains that this result shows that creativity isn’t just associated with the network but fundamentally depends on it. “We moved beyond correlational evidence by using direct brain stimulation,” she says. “Our findings highlight the causal role of the DMN in creative thinking.”

The activity of the network is changed in several disorders, such as ruminative depression, in which the DMN is more active than normal, possibly related to increased dwelling on negative internally directed thoughts. Shofty says that a better understanding of how the network operates normally may lead to better treatments for people with such conditions.

By characterizing the brain regions involved in creative thought, Shofty hopes to ultimately inspire interventions that can help spark creativity. “Eventually, the goal would be to understand what happens to the network in such a way that we can potentially drive it toward being more creative.”

Reference: “Default mode network electrophysiological dynamics and causal role in creative thinking” by Eleonora Bartoli, Ethan Devara, Huy Q Dang, Rikki Rabinovich, Raissa K Mathura, Adrish Anand, Bailey R Pascuzzi, Joshua Adkinson, Yoed N Kenett, Kelly R Bijanki, Sameer A Sheth and Ben Shofty, 18 June 2024, Brain.

DOI: 10.1093/brain/awae199

This research was supported by the McNair Foundation and the National Institute of Mental Health (grant number R01-MH127006.)

This work was a collaboration between researchers at University of Utah Health, Baylor College of Medicine, and Technion—Israel Institute of Technology.

Discussion about this post