Imagine if scientists could give us even more of a heads up before an opportunity to see a supercharged aurora display.

Researchers at Aberystwyth University in Wales say that they’ve figured out a way to do just that, by more accurately predicting the speed of coronal mass ejections (CMEs) before these powerful storms erupt from the surface of the sun.

“Our research not only enhances our understanding of the sun’s explosive behavior but also significantly improves our ability to forecast space weather events,” study lead author Harshita Gandhi, a solar physicist at Aberystwyth, said in a press release issued by the Royal Astronomical Society. “This means better preparation and protection for the technological systems we rely on every day.”

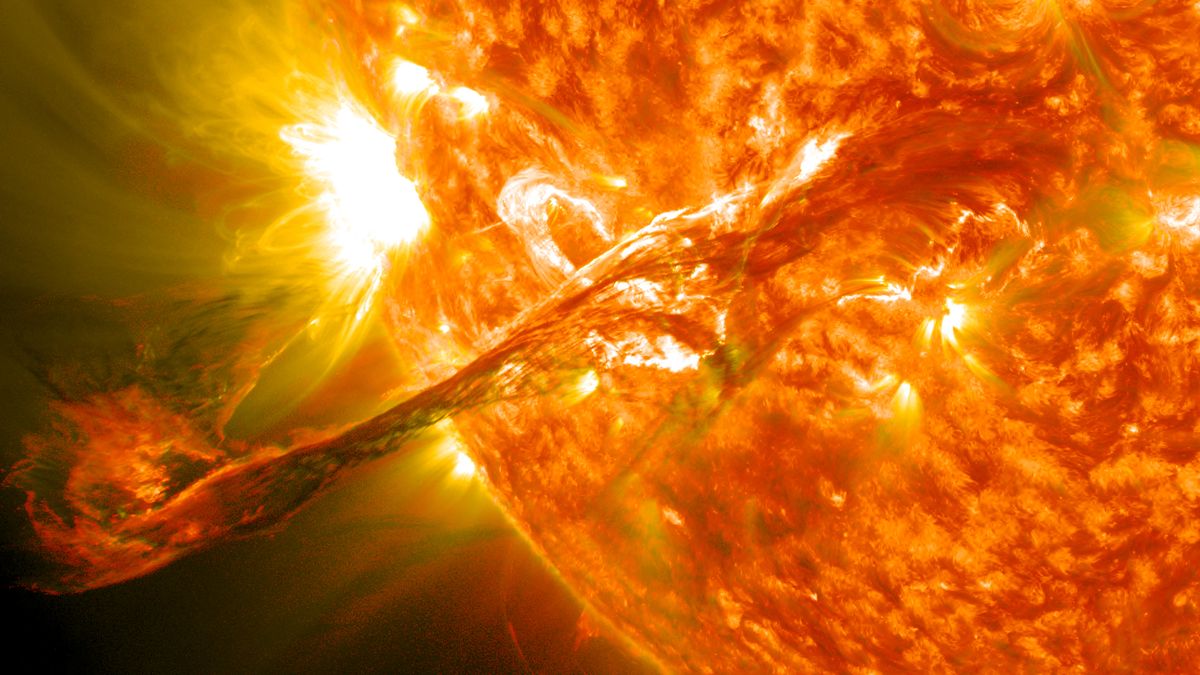

CMEs are powerful eruptions that send huge clouds of solar plasma streaking through space at millions of miles per hour. When CMEs are launched at Earth, they can intensify the auroras — the northern and southern lights — but also cause disruptions to satellites, the power grid and communications systems.

Gandhi and her team of researchers studied sunspots, active regions on the solar surface that serve as launch pads for CMEs and solar flares. They zoned in on a variable called “critical height” — the height at which a sunspot’s magnetic field becomes unstable, potentially leading to the birth of a CME.

Related: Solar maximum is in sight but when will it arrive (and when will we know)?

“By measuring how the strength of the magnetic field decreases with height, we can determine this critical height. This data can then be used along with a geometric model used to track the true speed of CMEs in three dimensions, rather than just two, which is essential for precise predictions,” Gandhi said. “Our findings reveal a strong relationship between the critical height at CME onset and the true CME speed. This insight allows us to predict the CME’s speed and, consequently, its arrival time on Earth, even before the CME has fully erupted.”

Gaining a better understanding of how fast a CME moves would help scientists produce more accurate forecasts and give more lead time before the plasma cloud arrives at Earth. Such forecasts can be quite tricky, especially when a sunspot fires off multiple CMEs in quick succession, as occurred this past May.

“Understanding and using the critical height in our forecasts improves our ability to warn about incoming CMEs, helping to protect the technology that our modern lives depend on,” Gandhi said.

The research team presented its findings to the Royal Astronomical Society during the organization’s National Astronomy Meeting on Friday (July 19).

Discussion about this post