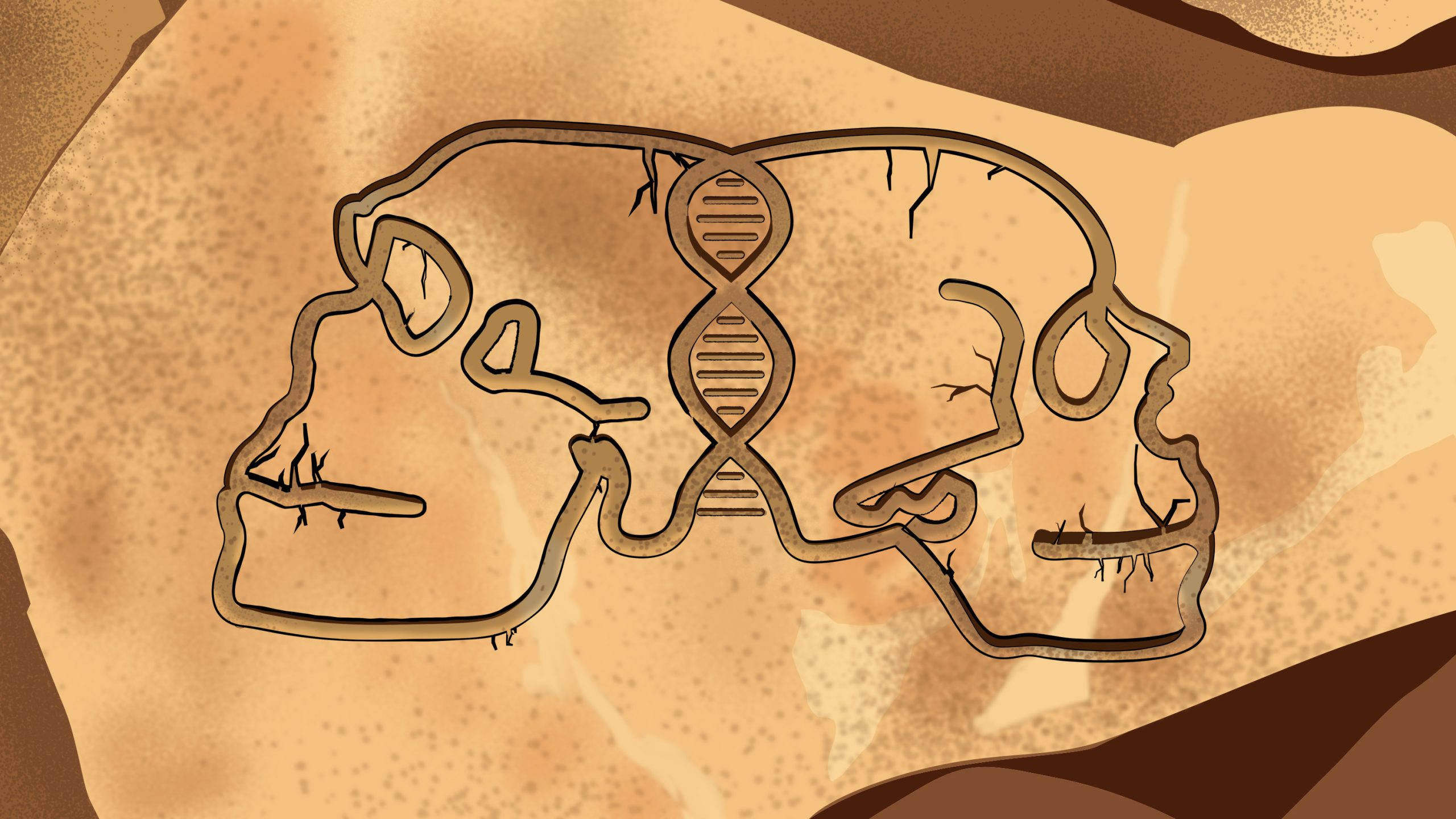

Modern humans have been interbreeding with Neanderthals for more than 200,000 years, report an international team led by Princeton University’s Josh Akey and Southeast University’s Liming Li. Akey and Li identified a first wave of contact about 200-250,000 years ago, another wave 100-120,000 years ago, and the largest one about 50-60,000 years ago. They used a genetic tool called IBDmix that uses AI, instead of a reference population of living humans, to analyze 2,000 living humans, three Neanderthals, and one Denisovan. Credit: Matilda Luk, Princeton University

Geneticist Joshua Akey states that modern humans and Neanderthals interacted for a period of 200,000 years.

New genetic research reveals extensive interbreeding and longstanding interactions between Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern humans, suggesting a more integrated history than previously understood and supporting theories of Neanderthal assimilation into modern human populations.

Since the discovery of the first Neanderthal bones in 1856, curiosity about these ancient hominins has grown. How are they different from us? How much are they like us? Did our ancestors get along with them? Fight them? Love them? The recent discovery of a group called Denisovans, a Neanderthal-like group who populated Asia and South Asia, added its own set of questions.

Now, an international team of geneticists and AI experts are adding whole new chapters to our shared hominin history. Under the leadership of Joshua Akey, a professor in Princeton’s Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics, the researchers have found a history of genetic intermingling and exchange that suggests a much more intimate connection between these early human groups than previously believed.

“This is the first time that geneticists have identified multiple waves of modern human-Neanderthal admixture,” said Liming Li, a professor in the Department of Medical Genetics and Developmental Biology at Southeast University in Nanjing, China, who performed this work as an associate research scholar in Akey’s lab.

“We now know that for the vast majority of human history, we’ve had a history of contact between modern humans and Neanderthals,” said Akey. The hominins who are our most direct ancestors split from the Neanderthal family tree about 600,000 years ago, then evolved our modern physical characteristics about 250,000 years ago.

Continuous Interaction Over Millennia

“From then until the Neanderthals disappeared — that is, for about 200,000 years — modern humans have been interacting with Neanderthal populations,” he said.

The results of their work appear in the current issue of the journal Science.

Neanderthals, once stereotyped as slow-moving and dim-witted, are now seen as skilled hunters and tool makers who treated each other’s injuries with sophisticated techniques and were well adapted to thrive in the cold European weather.

(Note: All of these hominin groups are humans, but to avoid saying “Neanderthal humans,” “Denisovan humans,” and “ancient-versions-of-our-own-kind-of-humans,” most archaeologists and anthropologists use the shorthand Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern humans.)

Using genomes from 2,000 living humans as well as three Neanderthals and one Denisovan, Akey and his team mapped the gene flow between the hominin groups over the past quarter-million years. The researchers used a genetic tool they designed a few years ago called IBDmix, which uses machine-learning techniques to decode the genome. Previous researchers depended on comparing human genomes against a “reference population” of modern humans believed to have little or no Neanderthal or Denisovan DOI: 10.1126/science.adi1768

This research was supported by the

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d1/82/d18228f6-d319-4525-bb18-78b829f0791f/mammalevolution_web.jpg)

Discussion about this post