A new conservation documentary, Ours, Not Mine, brings attention to the devastation that mining on the West Coast has, and will have, on the ecology and the surrounding communities.

The documentary investigates the heavy mineral sand mining on the West Coast, which includes the industrial-scale extraction of diamonds, gemstones and heavy mineral sands like zircon and ilmenite, which are extracted along the coastline between Columbine and the Orange River, including parts that are officially deemed Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas.

Mike Schlebach, big-wave surfer and CEO of Protect the West Coast, said that some of the richest grades in the world of natural minerals – used in many household products from paint to cosmetics – had led to a “gold rush for the industrial-scale extraction”.

The documentary juxtaposes long panning shots of open, untouched beaches in the Western Cape with shots of sand heavily imprinted with tracks from trucks and excavators left behind by mining companies.

The film, directed by Bryan Little and produced by Ana-Filipa Domingues, highlights how the destructive, single-use nature of this mining affects the environment and the local communities’ way of life and livelihoods – with impacts on agriculture, fisheries and nature-based tourism.

Rosie Shoshola, who has worked in the fishing industry in Lambert’s Bay since she was 11 years old, said in the documentary, “The sea is in your blood. When she’s in your blood you’ll never let her go.”

Fisherman Nico Waldeck said, “Where I live, we are dependent on nature. If you bring that type of development here, what’s going to get preference: Is it the people, or is it the money?”

By incorporating voices from indigenous and local people, like elders from the Khoi Griqua people, who depend on the land and ocean for their livelihood, the film takes a multiperspective approach to the issue.

Anthony Andrews, paramount chief of the West Coast Guriqua Council, which represents the bloodline families in the area, said during a mine-prospecting public participation meeting, “With our own research, we have seen how over the years we have not been recognised.

“We are saying to that minister [Barbara Creecy], ‘No. You don’t have the land…. This is our heritage and you can’t come drill holes in our heritage. We don’t give you permission.’”

Zolani Mahola, singer, actress and storyteller, wrote the song Blood in the Flowers with Emma van Heyn for Ours, Not Mine after meeting the people involved in the story.

Mahola told Daily Maverick, “I was really excited at the thought of seemingly very different people coming together from very different vantage points… talking about farmers, talking about the fishermen, talking about the indigenous San population, coming together… speaking for one thing… That for me is the new paradigm.

“I think so much of the changes that have happened in the world with the pandemic have shown us just how separation and separatism is old news… There’s so much more juice out of coming together from seemingly very different parts.”

Environmental impact

Professor Merle Sowman from the Department of Environmental and Geographical Sciences at UCT explained to Daily Maverick the environmental impacts the mining would have on the coastline.

Sowman said the impacts will depend on where the mining will occur – on coastal land, on beaches, in the nearshore or offshore – and the method of mining.

“These impacts range from loss of biodiversity, groundwater contamination, shoreline erosion, disturbance of dunes and cliffs, impacts on macrofauna, fisheries resources and marine megafauna, as well as impacts on scarce water resources, air quality and most importantly, access to the coast and fishing grounds.

“The main concern is the cumulative impact of all these different prospecting and mining activities on our coastal and marine systems.”

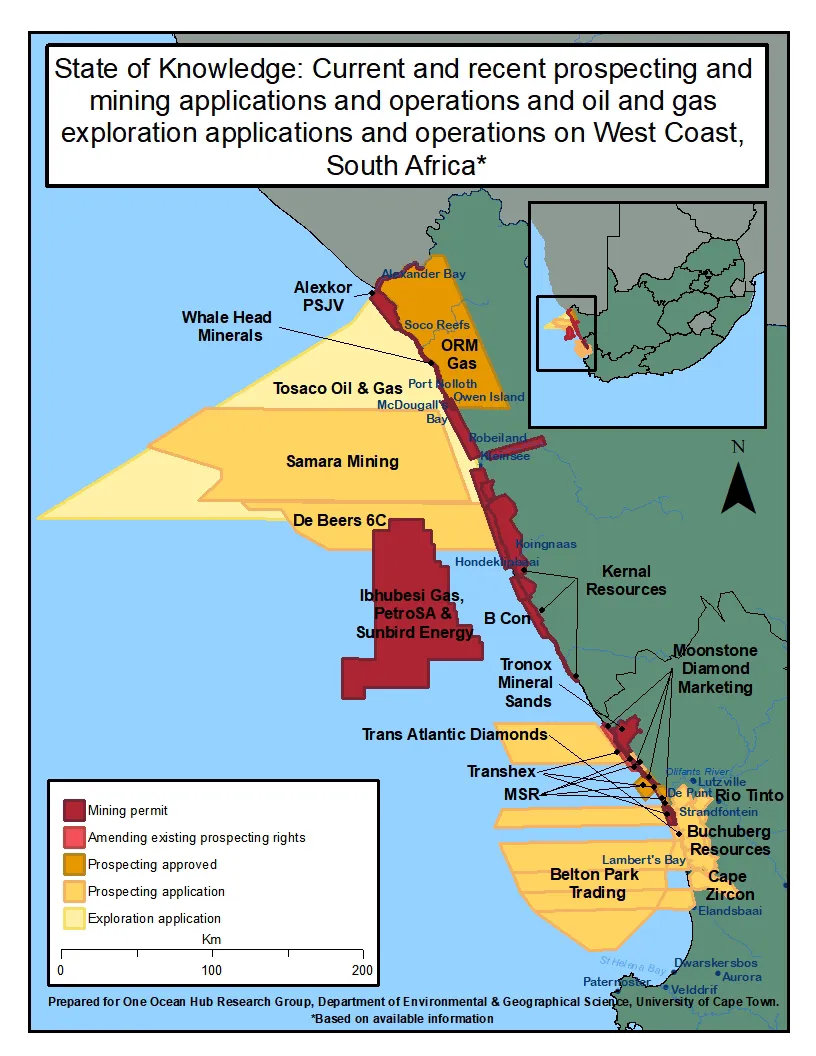

Researchers from the One Ocean Hub project in the Department of Environmental and Geographical Science at UCT have been tracking the various prospecting and mining applications on the West Coast and, with assistance from geographic information systems specialist Rio Button, have put together a “State of Knowledge” of prospecting and mining on the West Coast.

Sowman said the map is a work in progress and needs to be updated on an ongoing basis as the situation is changing so quickly.

For example, if you look at the map, the prospecting application submitted by Belton Park Trading earlier this year, which covers a large area offshore on the West Coast, has recently been approved.

“So, you can see, approvals are being granted across this coast quite rapidly,” said Sowman, referring to the map. “And my concern is that we don’t have an overarching understanding of the extent and scale of mining and what the potential cumulative impacts of all these activities are going to be on our marine and coastal environment.”

Pressure on government

Sowman said the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (DMRE) is responsible for approving applications for prospecting or mining on the West Coast – they grant the environmental authorisation.

“Of course, there is a lot of concern about the minister of DMRE having the authority to give environmental authorisation, when DMRE’s main mandate is the exploitation and development of our mineral resources,” said Sowman.

While the DMRE reviews and approves the environmental impact assessments, the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment is the appeal authority – meaning if civil society wants to appeal the DMRE’s authorisation, they have to appeal to Creecy.

“While there have been various appeals to the minister of the environment, she has generally not upheld these appeals and approved prospecting and mining in areas which, in my opinion, are unsuitable for mining,” said Sowman.

“A case in point is the recent appeal against environmental authorisation for prospecting on coastal land on the northern banks of the Olifants estuary, one of our most important estuaries in South Africa. Despite 35 appeals, the minister approved this application.”

Not considering the whole picture

Sowman said her main concern is around the number of environment authorisations that are being granted for prospecting and mining on the West Coast that don’t seem to be considering the cumulative impact.

“The key concern is that these decisions are being taken on an ad hoc basis,” said Sowman.

“There’s no government agency that is considering and assessing the cumulative impacts of all these mining applications and operations on our coastal and marine environment and how changes to these systems may affect our main economic activities – fishing, agriculture and tourism – on the West Coast.”

Letter to Minister Creecy

The documentary premiered on 6 December, just after Schlebach’s non-profit organisation Protect the West Coast sent a letter to Creecy on 25 November regarding the mining activity along the West Coast.

The letter highlighted how decisions are being made on an ad hoc basis without conducting a Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) or having in place an Environmental Management Framework.

The letter called on Creecy’s office to “ensure that current mining activities take place according to environmental conditions required by the relevant Environmental Management Programmes” and to “place a moratorium on all further prospecting and mining applications until a government-commissioned SEA has been completed for the West Coast to specifically identify whether mining, as a land use, is appropriate”.

As with the documentary, various parts of the community came together to show their support, from NGOs, to researchers, farmers, small-scale fishers, and the indigenous Khoi and San people.

The letter was accompanied by a petition to protect the West Coast, which at that stage had more than 58,000 signatures.

“Civil society is having to play a huge role in being the watchdogs and holding government to account for decisions being made,” said Sowman.

“I guess there’s concern that our government officials are not giving due consideration to the environmental and social impacts of these proposals and development applications.”

Out of sight, out of mind

Despite having devastating impacts on the environment and humans, the climate crisis and environmental or conservation issues are often ignored because of their “slow nature”, which Robert Nixon described as “slow violence” in his 2011 book, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor.

“By slow violence I mean a violence that occurs gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all,” said Nixon.

As with many environmental issues, it is difficult for the destruction of the West Coast to sustain the attention of the public as it is a crisis that spans over months or even years.

“I think what one is hoping is that through these kinds of interventions… you’re going to increase public awareness of what’s happening on the coast,” said Sowman.

“Because I think one of the problems is that many of these areas are far away from the public eye, and so people don’t really know what’s happening on the coast.

“If this kind of mining was proposed on Muizenberg beach or one of our popular beaches, there would be an uproar. But because these activities are taking place in areas that are out of sight and out of mind – although not for the local communities who live there – there’s not a high level of awareness of what’s going on.

“People are only going to feel the impact once access to their fishing grounds or favourite coastal recreation area is restricted.

“Right now, there’s a massive focus on seismic testing, which, of course, is a major environmental concern. But while that is occurring on the east coast, there’s this huge environmental threat along the West Coast, which is just not being given the same attention.” DM/OBP

Related Articles

![]()

Discussion about this post