A study reveals the Viking Age’s nuanced economic system through the Forsa Ring, indicating fines could be paid in oxen or silver, reflecting a complex economic integration with contemporary Europe.

A recent study by Stockholm University has provided a new interpretation of the runic inscription on the Forsa Ring, an ancient ring that dictated fines for specific offenses. The reinterpretation positions that ring as the oldest documented value record in Scandinavia and reveals how the Vikings handled fines in a flexible and practical manner. The research was recently published in the Scandinavian Economic History Review.

Overview of the Forsa Ring

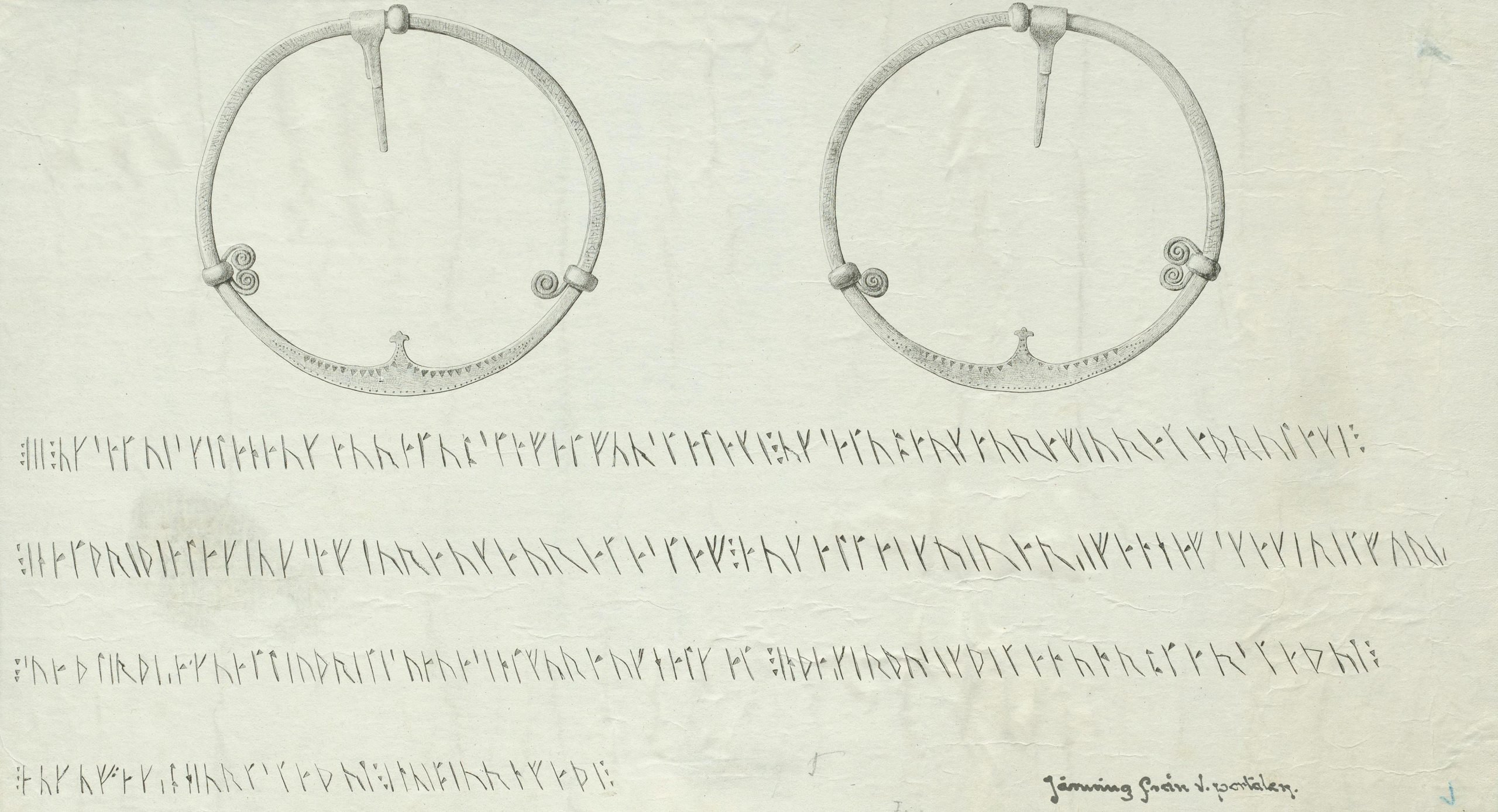

The Forsa Ring (Forsaringen in Swedish) is an iron ring from Hälsingland, dated to the 9th or 10th century. The runic inscription on the ring describes fines for a specific offense, where payment was to be made in the form of oxen and silver. The ring is believed to have been used as a door handle and is currently the oldest known preserved legal text in Scandinavia.

Reinterpreting Historical Texts

“The Forsaringen inscription “uksa … auk aura tua” was previously interpreted to mean that fines had to be paid with both an ox and two ore of silver. This would imply that the guilty party had to pay with two different types of goods, which would have been both impractical and time-consuming,” says Rodney Edvinsson, Professor of Economic History at Stockholm University, who conducted the study.

By changing the translation of the word “auk” from the previous interpretation “and” to the new interpretation “also,” the meaning changes so that fines could be paid either with an ox or with two ore of silver. An ore was equivalent to about 25 grams of silver.

“This indicates a much more flexible system, where both oxen and silver could be used as units of payment. If a person had easier access to oxen than to silver, they could pay their fines with an ox. Conversely, if someone had silver but no oxen, they could pay with two ore of silver,” says Edvinsson.

Historical Monetary Values and Integration

The new interpretation shows that the Vikings had a system where both oxen and silver served as units of payment. This system allowed for multiple types of units of accounts to be used concurrently, reducing transaction complexity and making it easier for people to meet their financial obligations. The new interpretation also aligns better with how the system functioned later according to later regional laws and is, according to Edvinsson, significant for our understanding of both Scandinavian and European monetary history.

“As an economic historian, I particularly look for historical data to be economically logical, that is, to fit into other contemporary or historical economic systems. The valuation of an ox at two ore, or 50 grams of silver, in 10th-century Sweden resembles contemporary valuations in other parts of Europe, indicating a high degree of integration and exchange between different economies,” says Edvinsson.

He has previously contributed to developing a historical consumer price index extending back to the 13th century, but this new interpretation provides insights into price levels even earlier in history.

“The price level during the Viking Age in silver was much lower than in the early 14th century and late 16th century, but approximately at the same level as in the late 15th century and the 12th century, when there was a silver shortage,” says Edvinsson.

Application of Modern Economic Theories

The study highlights the importance of using modern economic theories to interpret historical sources. By combining economic theory with archaeological and historical findings, new opportunities for interdisciplinary research and a deeper understanding of early economic systems are opened up.

Economic Dynamics in Viking Society

According to the new interpretation, an ox would cost 2 öre of silver, about 50 grams of silver, during the Viking Age. This corresponds to roughly 100,000 Swedish kronor today, if compared to the value of an hour’s work. The Forsa Ring’s fine amount was therefore quite high. One öre was likely equivalent to about nine Arabic dirhams, a currency that circulated in large quantities among the Vikings. A common price for a thrall was 12 öre of silver, or approximately 600,000 Swedish kronor today. The wergild for a free man, i.e., the fine paid to the family of the murdered to avoid blood revenge, was much higher, around 5 kilos of silver, which is about 10 million Swedish kronor today. The significant difference in value between a thrall and a free man reflects the power dynamics between free individuals and thralls in a slave society.

The relevant inscription of the Forsa Ring translated into modern English:

One ox and [also/or] two öre of silver to the staff for the restoration of a sanctuary in a valid state for the first time; two oxen and [also/or] four öre of silver for the second time; but for the third time four oxen and eight öre of silver.

Reference: “Applying a transaction cost perspective to decode viking Scandinavia’s earliest recorded value relation: insights from the forsa ring’s runic inscription” by Rodney Edvinsson, 24 July 2024, Scandinavian Economic History Review.

DOI: 10.1080/03585522.2024.2378465

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/34/31/3431771d-41e2-4f97-aed2-c5f1df5295da/gettyimages-1441066266_web.jpg)

Discussion about this post