After North Korea disclosed its first cases of coronavirus in May this year, many feared the worst for the isolated country’s unvaccinated and undernourished population.

For more than two years since the onset of the pandemic, the country’s totalitarian regime maintained that not a single person had tested positive for Covid-19 within its borders, a claim treated with scepticism by foreign public health experts.

But less than 10 days after suddenly admitting to a series of outbreaks across the country in May, an editorial in the state Rodong Sinmun newspaper declared that North Korea was “successfully overcoming” the crisis, trumpeting leader Kim Jong Un’s response and admonishing other countries for “weak” lockdown policies.

Since then, the North Korean authorities have claimed that there have been just 74 deaths resulting from 4.8mn cases in the country, or a fatality rate of approximately 0.0015 per cent, compared with 0.7 per cent in Britain, 0.3 per cent in the US and 0.1 per cent in South Korea over the same period.

On Saturday, North Korea reported not a single new fever case for the first time since it first announced the outbreak. State media praised “the organisational power and unity unique to the society of [North Korea].”

The twists and turns of North Korean propaganda in recent months have obfuscated the reality of the pandemic in the country. But they have also served to illustrate the regime’s complex and shifting relationship with reality itself.

“It is important for the North Korean leadership to show the people that it is fully in control of the situation,” said Rachel Minyoung Lee, a senior analyst at the Open Nuclear Network in Vienna and an expert on North Korean state media.

“But it is also risky for state media to create too large a disconnect between the regime’s claims and the experience of citizens,” she said. “The regime lives and dies by propaganda.”

In a rare televised speech in October 2020, Kim wept while describing the hardships his country faced as it wrestled with the threat of Covid-19 and a series of devastating floods.

“Our people have placed trust, as high as the sky and as deep as the sea, on me, but I have failed to always live up to it satisfactorily. I am really sorry for that,” said Kim, wiping his glasses as he praised soldiers toiling on flood recovery projects.

“My efforts and sincerity have not been sufficient to rid our people of the difficulties in their life.”

Analysts said that rather than a spontaneous display of emotion, the speech constituted the hardheaded execution of a shift in strategy that Kim had outlined in a letter to officials the previous year.

“What is important . . . is to make people deeply understand that the leader is not someone who is removed from the people, but who shares life and death and joys and sorrows with the people,” Kim wrote to propaganda workers in 2019.

“In the name of highlighting his greatness, we end up hiding the truth . . . [Only] when the people are captivated by the leader as a human being and comrade does their absolute loyalty gush forth.”

The memo put an emphasis on humility and transparency that has been reflected in regime messaging since Kim assumed control after the death of his father Kim Jong Il in 2011.

“For decades, North Korea claimed that its leaders didn’t have any flaws,” said Go Myong-hyun, a senior fellow at the Asan Institute for Policy Studies in Seoul. “But Kim Jong Un was different, admitting problems. It was a strategy to differentiate himself from his father, and it was successful.”

The coronavirus pandemic has presented the greatest challenge for Kim’s evolving media strategy. State media’s rapid acknowledgment in May of 2mn cases of an unspecified “malignant virus” took many experts by surprise.

“My guess is that when they said for two years they had controlled the pandemic, what they actually meant was that the virus had not taken hold in the capital,” said Christopher Green, senior consultant for the International Crisis Group.

“That’s probably the thing that changed. But in the spirit of turning lemons into lemonade, they have since pivoted to propagandising Kim Jong Un’s leadership in guiding the government response.”

Lee argued the regime was “trying to be more transparent not for transparency’s sake, but because they needed to raise awareness of the steps that citizens needed to take to combat the spread, and to secure people’s buy-in for that process”.

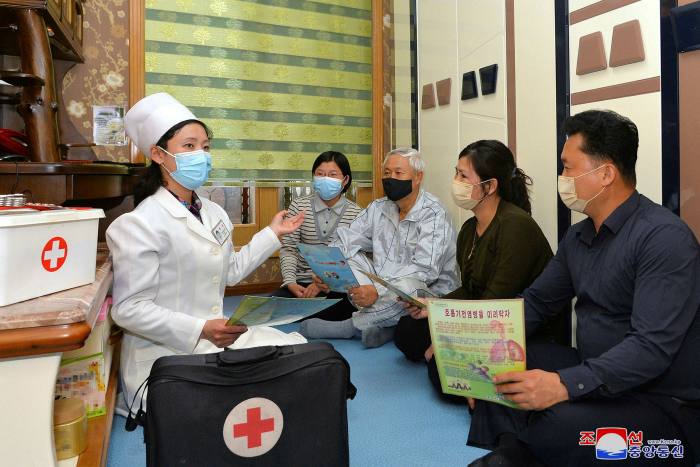

She described North Korean news bulletins featuring slick graphics with the latest official infection figures and a sombre public health official — dubbed the “North Korean Anthony Fauci” — presiding over calm daily briefings.

“The regime has clearly learned a lot from South Korean and western Covid broadcasts,” Lee added, noting the steady infiltration of foreign media into the country in past decades.

“But the North Korean population has also been exposed to too many outside influences for their leaders to continue to be mythologised as God-like figures.”

Green stressed the implausibility of the regime’s Covid-19 infection and death statistics, as well as North Korea’s widely ridiculed recent claim that the virus had entered via “alien things, climate phenomena and balloons” floated into the country from South Korea.

North Korea imported 3,554 invasive ventilators from China in June, a large increase since April despite a sharp downturn in trade between the two countries over the same period.

Pyongyang has also accepted some Covid-19 vaccines from China and started administering doses, according to Gavi, the global vaccine alliance. The regime previously refused offers of jabs through the World Health Organization’s Covax initiative.

“They have adopted a strategy of acknowledging problems when they cannot be denied,” said Green. “But their instinct to deny, obfuscate and hide has not fundamentally changed — this kind of regime has a structural problem with honesty.”

Additional reporting by Song Jung-a in Seoul

Discussion about this post