![]()

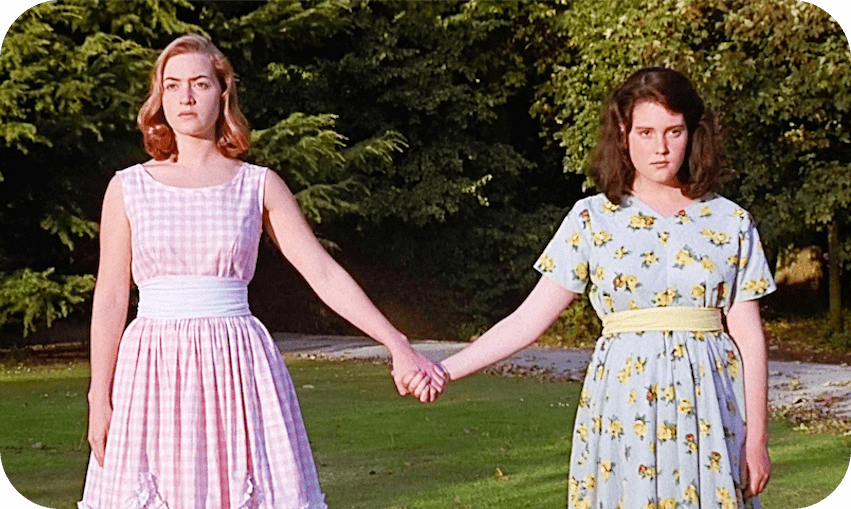

Photo: Stats NZ

Analysis – The first data from the 2023 census will be released on 29 May – and not before time. We will see how successful – or not – the census exercise was in achieving participation and coverage.

It is no secret past censuses have faced real challenges. We would not want to see a repeat of the poor return rate and low Māori participation that affected the previous census in 2018.

Stats NZ has said this latest five-yearly census has counted 99 percent of the population. But this figure is a combination of those who filled out the census forms (about 4.5 million) and others counted from existing government data (about half a million).

We can also cast forward by looking at the 12 months since the 2023 census was taken. In the year to March 2024, the key indicators are that the New Zealand population has changed significantly from where we were in March 2023.

Fertility continues to decline

In March 2023, the total fertility rate (births per woman) was 1.65 – well below the rate required for population replacement. In March 2024, the rate had dropped again to 1.52, a not inconsiderable decline in a single year.

Some forecasts had assumed New Zealand might stabilise at around the 1.6 rate. But the latest data show a steady downward trend. Internationally, and in New Zealand, the higher educational credentials of Millennial and Gen Z women, combined with their participation in the paid workforce, are driving this trend.

Additionally, the economic pressures facing those generations are having an effect. When it comes to decisions about having children, the cost of living, especially housing, and the increasing need for two incomes, are now much greater considerations.

When we reach a fertility rate of 1.3, as seems inevitable, New Zealand will join the ranks of the “lowest low-fertility” countries.

Aside from the actual fertility rate, there is also an absolute decline in births. In March 2024, there were 56,277 live births in New Zealand, compared with 58,707 a year earlier (2430 fewer births).

That is why the Ministry of Education is forecasting 30,000 fewer children in the education system by 2032.

New Zealand is now hovering around 56,000 births within a population of 5.3 million. Fifty years ago, in 1974, there were 59,334 births when the population was three million.

Photo: RNZ / Marika Khabazi

More arriving and many more leaving

The number of immigrant arrivals peaked in December 2023 at 244,763, a net gain of 134,445. Both figures significantly exceed the annual average from 2002 to 2019 of 119,000 arrivals and 27,500 net migration gain.

As of March 2024, arrival numbers have dropped back to 239,000, with a net migration gain of 111,100. Both numbers are still very high, but it suggests the coming year will see a further decline.

Still, New Zealand’s population grew last year by 2.8 percent, with net migration gain accounting for the bulk of it (2.4 percent). This is a very high annual growth rate compared to most OECD countries.

But the other side of the story is the surge in New Zealanders leaving. In the 12 months to March 2024, 78,200 New Zealand citizens migrated to another country, leaving a net loss of 52,500.

As Stats NZ notes with a degree of understatement, this exceeds the previous record of 72,400 departures and net loss of 44,400 citizens in the year to February 2012.

It is not unusual to see a net departure of New Zealand citizens. There was an average annual net migration loss of 26,800 from 2002 to 2013, when numbers were at the previous high. But the causes of the latest outflow deserve further analysis.

Māori near the million mark

Stats NZ confirmed the Māori ethnic population (those who self-identify as Māori) reached 904,100 in December 2023. The annual population increase for Māori was 1.5 percent. If this trajectory continues, Māori will number one million sometime in the early 2030s.

Māori fertility differs significantly to that of Pākehā. Māori have a much lower median age overall, Māori women have children at a younger age, with more children per mother born on average.

Stats NZ anticipates that by 2043, 21 percent of all New Zealanders will identify as Māori, up from 17 percent at the moment. For children, however, 33 percent will identify as Māori.

The so-called “kohanga reo generations” will be more immersed in tikanga and te reo, with major implications for New Zealand society and the political landscape.

Asian communities are growing and changing

The high levels of inward immigration will add to those identifying as one of the many Asian communities in Aotearoa New Zealand. (And we really do need to find another way of referring to these communities other than with the catch-all “Asian”).

Pre-Covid, the largest number of arrivals came from China. In the past two years, India has become the largest source country, followed by the Philippines and then China. To March 2024, there were 49,800 arrivals from India compared to 26,800 from China.

These immigration trends mean the next two decades (to 2043) will see the number of New Zealanders who identify with one of the Asian communities grow to 24 percent of the total population (25 percent for children).

For the moment, three-quarters of Asian community members are immigrants (born in another country), and quite a lot is known about them from past research. But it will be interesting to see how those born and educated in New Zealand forge their path, and what they will contribute.

The census tends to briefly focus attention on New Zealand’s changing population. But we need to spend more time putting the pieces together to understand how much the country is really changing. That includes looking at the trends between censuses – a lot can happen in five years, after all.

*Paul Spoonley is a distinguished professor in the College of Humanities and Social Sciences at Massey University

– This story was originally published by The Conversation.

Discussion about this post