Evolutionary geneticist and choral singer Jenny Graves has performed Joseph Haydn’s masterpiece, The Creation, on many occasions. The famous oratorio chronicles the seven days of biblical creation as described in the Book of Genesis. Yet Graves, who has spent the past 60 years studying the wonders of evolution, grew tired of singing about Adam and Eve. So she penned a secular retelling of our origin story — drawing from scientific discoveries in cosmology, molecular biology, evolutionary genetics, ecology and anthropology — and teamed up with a poet and a composer to bring the 110-minute choral work to fruition.

The piece, Origins of the Universe, of Life, of Species, of Humanity, is bold, compelling and funny, much like Graves. One of its most provocative verses, “No cosmic hand guides diversity,” comes early in the seventh movement. A chorister protested, suggesting she revise the wording to be more allegorical or vague. “I don’t want it to be vague,” Graves recalls saying. “I want the origin from science — and science is what I’m going to use.” One tenor left during rehearsals, telling Graves they couldn’t sing something they didn’t believe in. She smiled her disarming smile and responded, “Oh, why not? We do that all the time. Do you believe in Santa Claus?”

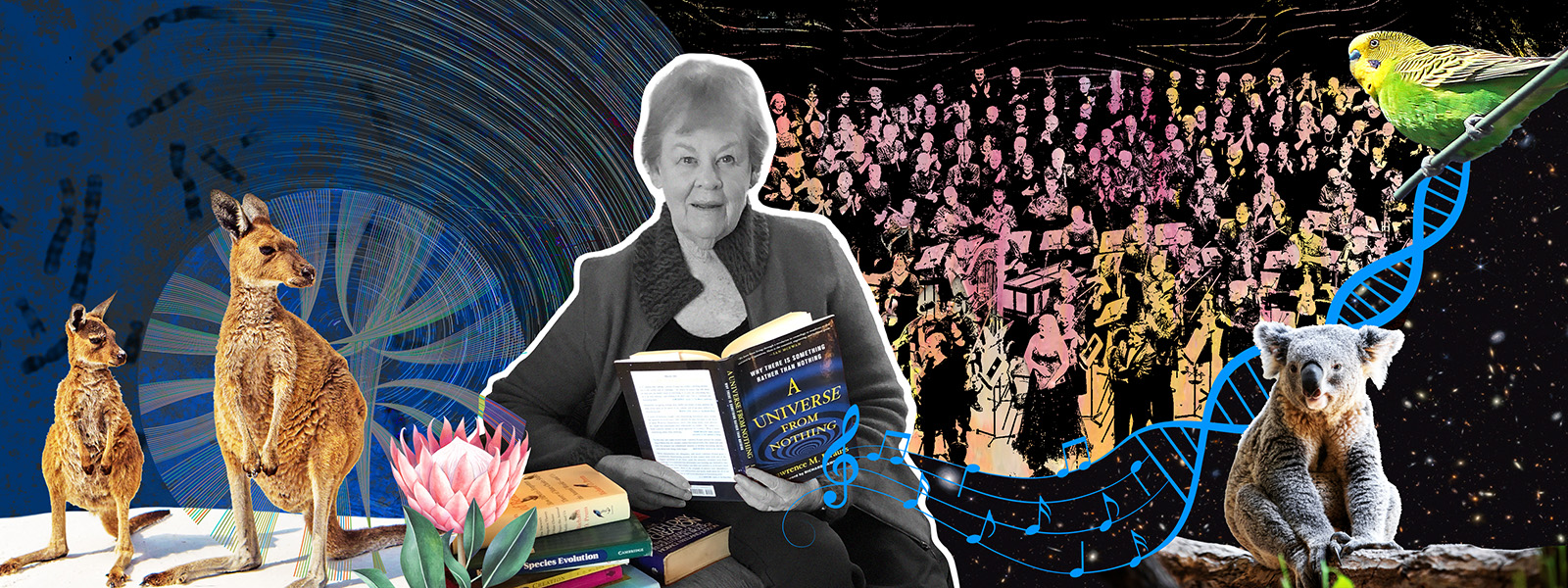

Most people embraced Graves’s vision, and last summer, she received a standing ovation after performing Origins alongside a 100-voice choir, full orchestra and four soloists at a glittering concert hall in Melbourne, Australia. Biologist Harris Lewin, who has known Graves since the 1990s, says he was blown away by Graves’s latest achievement.

“She’s absolutely brilliant. She’s creative. She’s original,” he says. “There’s no one else like Jenny.”

Origins of the Universe, of Life, of Species, of Humanity was performed in 2023 in Melbourne, Australia, during the International Congress of Genetics.

CREDIT: © 2023 HEIDELBERG CHORAL SOCIETY, JENNIFER GRAVES, LEIGH HAY AND NICHOLAS BUC

Inspired by a budgerigar

Graves was born in Adelaide, South Australia, a city known for its vibrant cultural scene and parklands brimming with wildlife. Both her parents were scientists: her father a soil physicist and her mother a geography lecturer. But as a child, she didn’t feel a particular pull toward science. She liked reading, writing and art. When she first took biology, she hated the subject — it seemed like a bunch of facts with no rhyme or reason.

Then, one day, her high school teacher gave a lesson on genetics, using the budgerigar (also known as the common parakeet) as an example. The teacher explained that when you crossed the blue budgerigar with the yellow budgerigar, all the offspring were green; when you crossed the green budgerigars with each other, a quarter of the progeny were blue, half were green and a quarter were yellow. Suddenly, it all made sense. “‘Wow, there are rules; there are rules, after all,’” says Graves. “Of course, I didn’t discover the real rules of biology, which are evolutionary rules, and I discovered that much, much later.”

Graves studied genetics at the University of Adelaide, conducting undergraduate research on sex-determining chromosomes in kangaroos. She won a Fulbright grant to get her PhD at Berkeley. It was the 1960s, the decade of peace, love and music. Anti-war protests were a fixture on campus. Graves met her husband while playing star-crossed lovers in a musical dubbed NucleoSide Story, a riff on West Side Story, about the warring departments of molecular biology and biochemistry. He later encouraged her to join a choir with him; the couple, who have two daughters and three grandchildren, have been making music together ever since.

At Berkeley, Graves designed complicated experiments that forced mouse, hamster and human cells to fuse together in petri dishes. When she moved back to Australia as a lecturer at La Trobe University in Melbourne, a colleague suggested she use her cell hybrids to map genes in Australian mammals. Initially, she was hesitant to study the local flora and fauna, worried that it might limit the impact of her work. But she eventually realized she could glean a lot of information by comparing the genomes of distantly related animals.

“I got totally transfixed,” she said. “It’s sort of like a giant jigsaw puzzle.” It was the early days of gene mapping, and scientists knew little about the mammalian genome. “We only had 16 genes mapped in humans and not a single one in kangaroos. And so people had wondered, how conserved is our genome?”

Highly conserved genes are similar across different species and have been maintained over millions of years of evolution. These genes typically stick around because they serve a vital function, such as in reproduction or metabolism. They also serve as signposts for scientists trying to decipher how the genome is arranged and how it has changed as various species have evolved. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Graves was part of a cadre of scientists who began comparing genes and chromosomes from a menagerie of creatures, including kangaroos, platypuses, cats, cows, pigs, monkeys, birds and, of course, mice and humans, laying the foundation for a field of study that would later be known as comparative genomics.

Using this comparative approach, Graves challenged a textbook paradigm known as Ohno’s law. Proposed by the biologist Susumu Ohno, the law stated that the X chromosome (one of the chromosomes involved in dictating an animal’s sex) carried the same genes in all mammalian species. But Graves showed that genes on the short arm of the X chromosome in humans mapped to a different chromosome in kangaroos. In a career retrospective in the Annual Review of Animal Biosciences, she recalls visiting Ohno at his office at the City of Hope cancer center in the greater Los Angeles area, and sharing the news. He didn’t seem to care that her marsupials had broken his law. Instead, he led her to his computer to show off his latest project: turning DNA sequences into musical pieces.

The incredible shrinking Y

Graves’s interest in sex chromosomes intensified after she got caught up in the race to discover the gene on the Y chromosome that determines the development of male sexual characteristics. Geneticist David Page thought he had found the testis-determining gene, which he called ZFY, and reached out to Graves to confirm his discovery in kangaroos. Instead, her student Andrew Sinclair showed that ZFY was the wrong gene. “It was on chromosome 5, which is a strange place for a sex gene,” says Graves. Sinclair went on to find the real sex-determining region on the Y chromosome, and aptly named it SRY.

Then, in 1992, Graves experienced a significant setback: a near-fatal cerebral hemorrhage followed by 18 months in rehabilitation. Graves was unable to read or walk at first. But she could think and type, so she wrote five grant proposals. They all got funded.

“She was resilient,” says Rachel O’Neill, who joined the Graves lab as a PhD student around that time. O’Neill wasn’t aware of her boss’s health issues until much later. But she remembers watching as Graves furiously wrote grants, all while fighting for access to the same lab space and resources afforded to her male colleagues. “We talked about the dynamics of being one of the few women in the field in Australia, and how easy it was for people to dismiss what she said,” O’Neill recalls. “She had a talent for letting it just wash off her.”

When O’Neill received her first manuscript rejection, she sought advice from Graves, who told her that every manuscript was a fight and that she just had to keep fighting. Graves pulled out her first rejection letter, in which the reviewer had basically written, O’Neill recalls, “I didn’t like it, and my friends didn’t either.” Graves told O’Neill that’s what all rejections say, and if she could persuade the naysayers to like her work, she could do anything. O’Neill said she still shares that story with her students at the University of Connecticut, where she is a molecular biologist. And she thinks of it every time she gets a particularly nasty review.

Over the years, Graves grew adept at winning over salty scientists and uninterested undergrads alike. As a teacher, she often turned to her love of music to get her point across, writing songs about genetics to liven up her lectures. “They were so amazed — in a boring summer class I’d suddenly sing The Mutant’s Lament or Love’s a Plasmid,” she says. “I run into my old students all over the world — in airports in France and that sort of thing — and they will say, ‘I’ll never forget your second-year lectures!’”

In 1999, Graves was elected to the Australian Academy of Science. Shortly after, she took a research position at the Australian National University in Canberra, where she founded the comparative genomics department. There, she infamously predicted that the human Y chromosome was shrinking and would disappear in about 4 million to 5 million years. The prediction raised a furor as people fretted about the fate of our species. “We haven’t been through 1 million years — we think we’re worried about the Y chromosome in 4 million years?” she recalls. “I thought that was extremely funny.”

“She’s a provocateur,” says Lewin, “and she relishes being in a place that will get people to think. By saying the Y will disappear, OK, that gets a lot of attention. What it does is, it draws you to the actual science that she and others working in the space are doing.”

Graves has generated scads of thought-provoking findings. She showed that high temperatures can reverse the sex of the bearded dragon, and that the platypus has 10 sex chromosomes unrelated to the XY system of other mammals. Her research has yielded important insights into the evolution of genes and chromosomes across all animal species, including humans. Eventually, she was named a Thinker-in-Residence at the University of Canberra, giving her more freedom to focus on big ideas.

A ‘preposterous idea’

In 2016, Lewin invited Graves to the Wellcome Trust in London to speak at the official launch of the Earth Biogenome Project, an ambitious effort to sequence all 1.8 million known species of plants, animals, fungi and other eukaryotic life on the planet. Lewin says her talk helped to catalyze the multibillion-dollar project in ways few others could.

Graves picked examples from different branches of the tree of life, describing unexpected discoveries that have shaped the understanding of biology. How the single-celled Tetrahymena was used to discover telomerase, an enzyme involved in aging and cancer. How arrow-shaped flatworms known as planarians can regenerate after being chopped into pieces, informing research on stem cells and healing. Graves argued that if such knowledge could be gleaned from just a few species, imagine what can be learned from sequencing everything else.

“She’s a really great speaker and performer,” says O’Neill, one of the thousands of scientists who joined the project. “When she speaks, everyone in the room listens.”

In recent years, Graves has taken her act to a new level. She recognized that creating a science-based sequel to Haydn’s The Creation was a “preposterous idea.” But when she finally sat down to do it, she wrote the whole thing from start to finish in a week and a half. Poet and fellow chorister Leigh Hay helped edit the words, and composer Nicholas Buc put them to music.

Jenny Graves, poet Leigh Hay and composer Nicholas Buc talk about what Origins means to them in this short video.

CREDIT: LA TROBE UNIVERSITY

“I think science is very beautiful,” says Graves. “Just look at the James Webb telescope images: Beautiful science is right there. Look down at the microscope: beautiful science. The idea of expressing beautiful science and beautiful music always really appealed to me.”

Graves’s Origins portrays not just the beauty of science but also its ugly side. It spans the Big Bang to the sixth mass extinction, vividly describing the molecular underpinnings of life and the uniquely human endeavor to understand it. One of the most popular moments gives Rosalind Franklin due credit for her role in the discovery of the DNA double helix, which earned the “antiheroes,” James Watson and Francis Crick, a shared Nobel Prize.

Given the choice, Graves wants Origins to be her legacy. She would love for people to listen to her sweeping science oratorio a hundred years from now.

“Science is a very creative discipline; it requires you to think creatively to outwit nature and find out the secrets. But it is very different creating something like Origins,” she says.

“Some of my surprising results turned out to be really important — I love them, they’re terrific, and I think they’re creative — but if I hadn’t done them, someone else would have. But if I hadn’t written Origins, nobody else would have.”

Discussion about this post