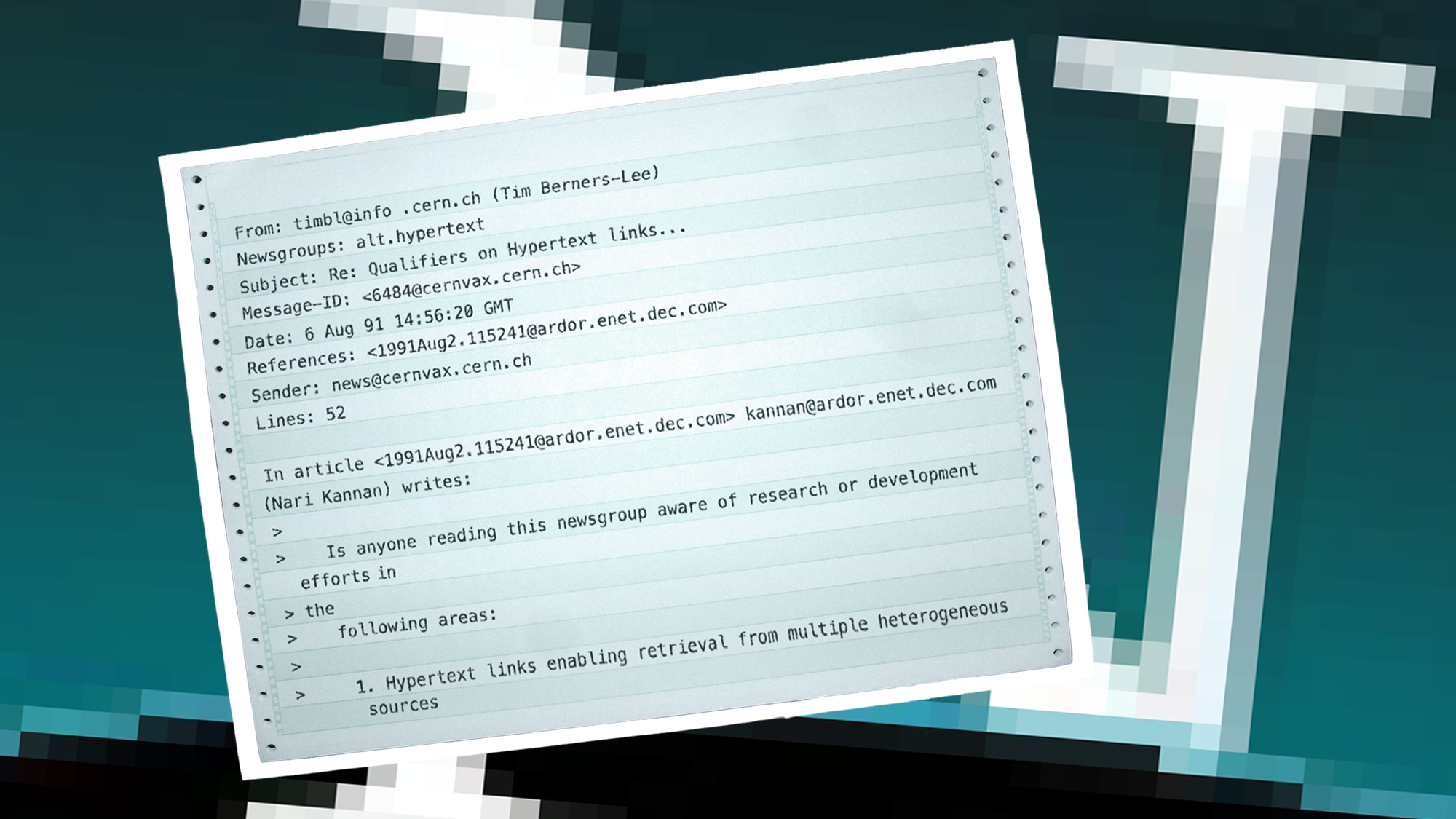

On August 6, 1991, in a little-known newsgroup–an early-days, primitive version of an internet forum–called alt.hypertext, a soon-to-be-famous computer scientist posted something that would change the technology landscape—and the world—as we knew it. It was a response to a query from one of his fellow newsgroup nerds, who asked if anyone knew of development efforts in the form of “hypertext links enabling retrieval from multiple heterogeneous sources of information?” In other words, could the early Internet become easier to join and navigate?

Tim Berners-Lee, a British computer scientist at CERN (the European Organization for Nuclear Research), used that forum to announce to the world his new initiative, writing, “The WorldWideWeb (WWW) project aims to allow links to be made to any information anywhere. The address format includes an access method (=namespace), and for most name spaces a hostname and some sort of path.” Before Berners-Lee’s novel idea, to navigate the internet required knowing specific protocols like Telnet or FTP to connect to other servers, which did not have friendly names like popsci.com, but rather arcane computer names that could not easily be discovered. Online discussions involved participating in message-based bulletin board systems enabled by services like Usenet or CompuServe. In his post, Berners-Lee even included one of the first URLs, or Uniform Resource Locators, in his newsgroup post, where more information could be found: http://info.cern.ch/hypertext/WWW/TheProject.html (the link still works).

With that, the World Wide Web made its debut. Later, an October 1998 Popular Science technology update acknowledged the Web’s anniversary, noting that “Internet use is really about the growing popularity of one part of the Net—the World Wide Web.” The article included early web user statistics such as “77 percent of all Web users are between the ages of 18 and 49,” and 10 million people in the US had shopped online during the first quarter of 1998. It highlighted “portals” like Yahoo, touting services like “personalized news.” With more than 2.6 million websites already available in 1998, the Web had arrived. Seven years earlier, it was still just one computer scientist’s idea.

Berners-Lee had first proposed his idea to his CERN supervisor, Mike Sendall, more than two years before the prophetic post, in March 1989. But Sendall’s response had been tepid. According to the World Wide Web Foundation, CERN never funded the project, although by September 1990, Sendall granted Berners-Lee time to work on it independently.

In the August 6 post, Berners-Lee shared information about the WorldWideWeb project’s progress and invited collaboration, explaining the basic concepts behind the web, such as HTML, HTTP, and web browsers that could access and display documents stored on servers. Although the August 6 post has been celebrated for announcing the World Wide Web, it’s worth noting that Berners-Lee also spelled out Open Source principles. He offered up his code for free, encouraged others to “hack it,” and made available all his documentation and data. “Collaborators welcome!” he wrote.

In 1993, the release of the Mosaic web browser (written by Marc Andreessen) democratized internet access, offering a graphical user interface that made the internet more accessible, converting text-based prompts into point-and-click pages. The subsequent introduction of Netscape Navigator (also Andreessen) further accelerated engagement. As noted by Popular Science, by the late 1990s, the internet—via the Web—had begun to affect commerce, media, and personal communication. It might be said that today’s glitzy social media sensations like Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok could trace their roots to a humble newsgroup post written in a crude monospace font on August 6, 1991.

Discussion about this post