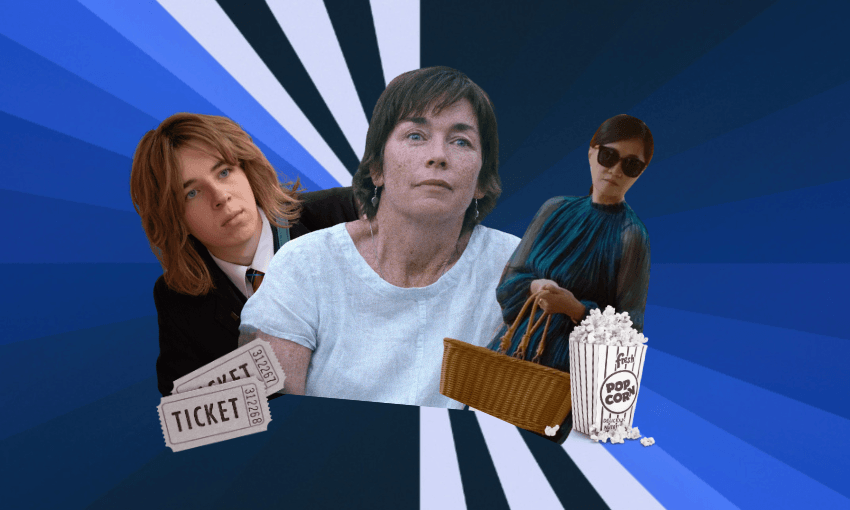

Week two highlights of Whānau Marama: The New Zealand International Film Festival, including a post-apocalyptic animal animation and a trip through the 1970s Christchurch punk scene.

Sleep

I am not a horror lover (a scaredy cat in fact) but I adored this film. Yes, it’s scary, but not horribly so. Sleep is a South Korean film which has been described as black comedy, horror, mystery and thriller, with marriage as its central subject. It follows a sweetly enamoured couple with a tiny dog and a baby on the way and jumps right into the plot when the husband sits up during the night and says, “someone’s inside.” Over a few nights, his sleepwalking escalates, and becomes menacing. It is truly horrifying that your loved one could turn into a monster as you sleep in an enclosed space with them. It’s so tightly written and so well put together that it’s hard to believe it’s the writer-director, Jason Yu’s first feature. Though the horror starts right away, it is well punctuated and perfectly balanced with lol moments and loveable characters. / Gabi Lardies

Flow

We’re set in a lush, rapidly flooding landscape abandoned by humans, at an unclear point in time: often it feels post-apocalyptic; at other moments, prehistoric. Bit by bit, a cat in a sailing boat bands together with a capybara, ring-tailed lemur, labrador and strangely regal white bird. Together they drift through shifting, picturesque landscapes – there are sea monsters, abandoned wooden carvings of enormous cats, gorgeous waterlogged cities and heavenly cloudscapes – figuring out how to survive. The climate crisis isn’t discussed (there is no dialogue) but looms in the background; the biblical overtones are resonant but also quiet.

The film’s main focus is the growing bond between the unlikely gang of animals, which is all the more moving for not being saccharine or overcooked: even as the animals develop bonds of loyalty and trust, they’re also wary, irritable, selfish. Initially the animation felt off in a way I can only describe as “too computery”, but overall the film is carried by its realism: the ripples of laughter in the audience always came from the cat behaving exactly like a cat, the lemur behaving exactly like a lemur, and so on. Sprinkled on top are just a touch of fantasy (the leviathans!) and heavenly transcendence. Otherwise, we’re firmly on earth. It’s a very special movie. Highly recommend. / Madeleine Holden

Pepe

This is a film for people that like weird movies and aren’t at all in a rush – it was fittingly described as “unclassifiable” by Carlo Chatrian, artistic director of the Berlinale. Narrated by the ghost of Pepe, a hippo whose parents were taken from Africa to Colombia for the private zoo of drug lord Pablo Escobar, the narrative is slow and a bit disordered. The writing certainly goes for poeticism over story. Pepe was one of the first hippos to escape into the river system after Escobar died in 1993 and the zoo was left uncared for. He was eventually killed under state orders, but many more of the herd live freely and have bred and flourished in the jungle. The film has a lot of long artistic shots that are photographically interesting but, in terms of pushing a narrative forward, I was not convinced we needed to see the hippos being transported through ten different shots. / GL

Brief History of a Family

If you watched Saltburn and found yourself supremely disappointed by the hack ending (among other things), might I suggest you check out Brief History of a Family. The debut feature from Jianjie Lin, Brief History follows a one-child family in China who find themselves drawn, in different ways, to teenager Yan Shuo. Tu Wei befriends him at school, Tu Wei’s mother enjoys his interest in her life, and Tu Wei’s father sees himself in the enigmatic young man.

On the surface, the events that play out (for the most part) are ordinary snapshots of home life. But it’s unsettling and never clear whether you’re watching a family drama or a suspenseful thriller. In the end it’s both. The score is loud, literally. Rather than play to the expected audience response, the score is closer to sound design and pierces through otherwise mundane moments. At times it felt overbearing, and in a way that was not deliberate, but it was a small discomfort for a beautiful and assured first feature. / Madeleine Chapman

Seeking Mavis Beacon

This documentary and the central story had capslock YARN written all over it. Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing was a popular educational software launched in the late 80s that taught millions of people how to type. There was no “real” Mavis Beacon, but the warm and encouraging black woman on the product’s packaging was a real person, named Renée L’Espérance. L’Espérance was discovered working at a department store and was paid $500 for the use of her image as the face of the programme. The company that developed Mavis Beacon went on to be sold for hundreds of millions of dollars in the mid 90s.

Filmmakers Jazmin Jones (director) and Olivia McKayla Ross (associate producer) set out to find L’Espérance after she “disappeared”. They hold Beacon up as an example of much needed representation and an icon of black history. She exists as a cypher for our relationships with technology and stands as an early example of the preference for AI assistants or avatars to be servile women.

There are echoes of the podcast Missing Richard Simmons as the DIY investigation twists and turns and ultimately ends up having to centre the filmmakers’ own journey and friendship, rather than L’Espérance’s. As a result, the film gets quite heavy with grand sociological and philosophical theory and morphs into an examination of parasocial relationships, internet culture and an earnest attempt to see a hero get her dues.

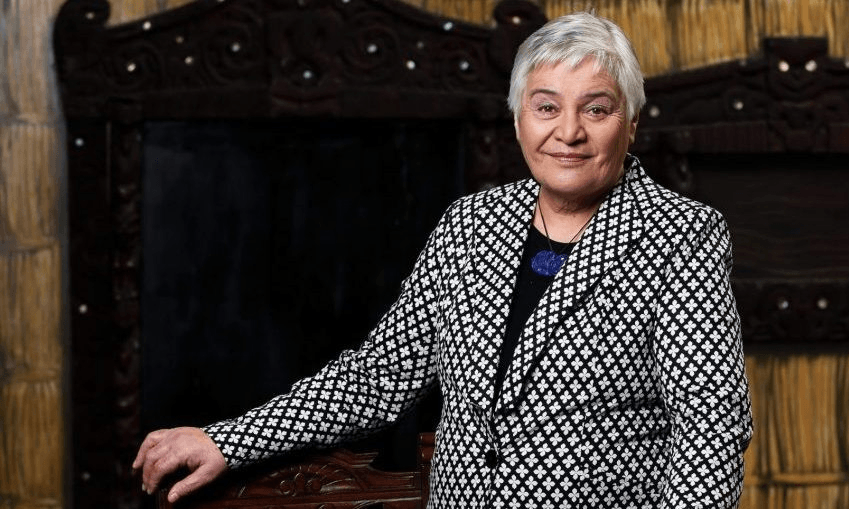

It’s a heartfelt, beautifully shot debut that excavates enough insight into pop culture history and current day fan culture to counterbalance what is at times, a painfully self-conscious and scattered documentary. / Anna Rawhiti-Connell

Janet Planet

I came to this movie for Julianne Nicholson (who stole the show in Mare of Easttown, and everything else she’s ever been in) and left with Zoe Ziegler (who plays Lacy, Janet’s daughter) firmly in my heart, right alongside the other introverted redhead with glasses who lived through ill-fitting 90s fashion and obsession with acupuncture (young me).

This slow-moving (at times too slow) – but piercing – portrait of a mother-daughter relationship is charming, and searching and nostalgic for the 90s: The knee-length T-shirts, the trolls, the FEMO, the microwaves, the piano lessons with formidable elderly women with a metronome and a creepy doll and the bowl of lollies that baits a trier back.

The story is structured in episodes: each one exploring a newcomer in the pair’s lives (either boyfriends, or needy acquaintances). Ziegler’s performance as shy, lonely Lacy is tender without being twee, deadpan without being Wes Anderson. She’s extraordinary. Nicholson, though, is a dream. A gorgeously freckled dream. She plays a searching woman-mother with a strength and grace so subtle it’s easy to forgive her bad choices, even overlook that they’re bad. Her role as Janet Planet is an exploration of the still-maturing idea of womanhood in the 90s, and pseudo-psychology before it emerged into fully-blown wellness culture. Sophie Okenedo has a scene-stealing presence in the middle of the movie; a tragic-comic turn that I thought for a moment might hover into cruel satire but it never does. This is filmmaking at its most honest and skilful: critical without judgement. All of this quiet drama set inside a dazzling Massachusetts summer: the sounds of birds, bees and flying things is a constant energy. Sunlight through lush, lovely trees and undergrowth. This is an intimate coming-of-age that will haunt you with a smile. / Claire Mabey

I second everything Claire has to say about Janet Planet – there was less drama than the description of the movie implied, but it captures the experience of being a child desperately observing everything about the world (and sometimes being kind of annoying about it) perfectly. The film takes place primarily in a big wooden house with lots of turrets, and at one point Sophie Okenedo’s character, Regina, points out that it has been easier for Janet to retrain as an acupuncturist because she inherited money, an awareness of privilege that lends a tension to the rest of the movie. So many beautiful shots of wooden floors and the sound of crickets make this a very relaxing, if slightly drifting and plotless, movie. / Shanti Mathias

Head South

Johnathan Oglivie got as close as one could to rarking up the patrons of Christchurch’s Lumiere Cinema last night with his call for a “coup d’etat” against the likes of Marvel, Netflix and even A24. Quoting Jean Luc-Godard, he waxed lyrical about how America has colonised our imaginations, and how Aotearoa continues to undervalue itself creatively. In keeping with his intermittent use of French (also a running gag in the movie), the speech was the perfect “hors d’oeuvres” before being transported back to Ōtautahi in the late 1970s for a coming-of-age story about a kid trying to infiltrate the local music scene.

There was a lot to love about Head South. I loved the central boy-makes-band School of Rock-style storyline. I loved the performances from the wide-eyed, perpetually smiley Ed Oxenbould as Angus and the acting debut of Stella Bennett, aka Benee, as no-nonsense chemist clerk Kirsten. But it was Márton Csókás who truly devoured every scene as Angus’s bizarrely hypnotic father Gordon, dripping in weird droll musings as he wrangles with the recent departure of his wife. “Beautiful flame, isn’t it” he says, glassy-eyed as their Flymo mower burns (long story). “It’s because of the toxins in the plastic.”

Where I got slightly confuddled was during the bits involving mysterious Londoners, drugs, and nude photography in exchange for a bass guitar. The film’s autobiographical nature – “this is not a lie” reads the opening frame – possibly explains why things sometimes felt a bit akimbo. Life isn’t always as tidy and structured as a big Marvel movie, and there’s no better example of that than a genuinely shocking heel turn during the final act. But with plenty of laugh-out-loud moments, thrilling iconic Christchurch locations and a plethora of 1970s references (many knowing chuckles in the crowd were had), it’s a fun and nostalgic film with a certain “je ne sais quoi”, as Gordon might say. / Alex Casey

Read our week one reviews here.

Click here to see the full programme from Whānau Marama: The New Zealand International Film Festival

Discussion about this post