Billions of years from now, any alien civilization searching for life in the vicinity of the solar system would find Earth not as our beloved pale blue dot in its orbit but as bits and pieces of metal polluting our sun.

That’s because stars with masses around that of the sun are destined to die in a drawn-out episode during which they swell up to hundreds of times their current sizes, swallowing up any orbiting planets within reach.

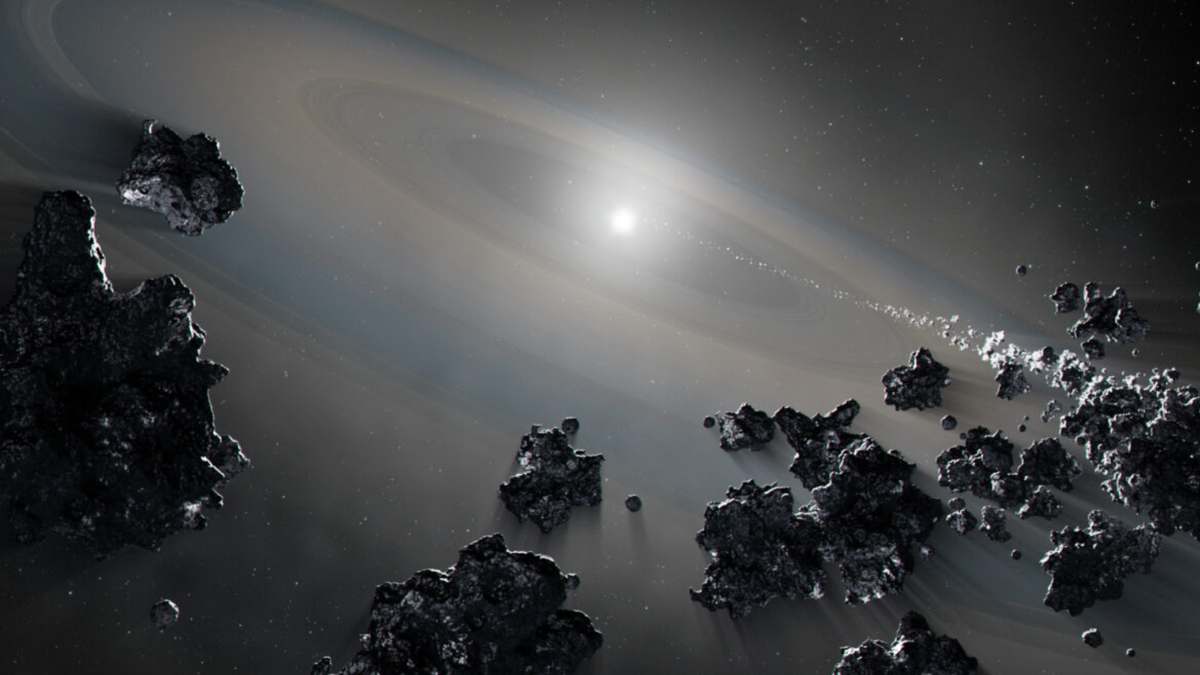

After this puffed-out “red giant phase,” the final fates of these stars are as shrunken, dying embers of a star, a stellar remnant called a “white dwarf.” These dead stars can become coated with the remains of the worlds that once orbited them, which they have since consumed.

Thus, these white dwarf stars can serve as unique, if distant, laboratories for studying the insides of demolished planets that are otherwise out of reach for telescopes.

Related: White dwarfs are ‘heavy metal’ zombie stars endlessly cannibalizing their dead planetary systems

“It’s the only bona fide way to actually figure out what planets outside the solar system are made of,” Keith Hawkins, an astronomer at the University of Texas at Austin, said in a statement. “[That] means finding these polluted white dwarfs is critical.”

Although the universe is sprinkled with many such “polluted” white dwarfs, finding them is by no means easy. Tell-tale signs of planetary pollution, like iron and magnesium, are extremely subtle and difficult for telescopes to discern for intrinsically faint white dwarfs.

Astronomers typically scout troves of telescope data in search of the smoking gun evidence for further scrutiny with follow-up observations, a time-intensive effort that has so far found about 1,400 polluted white dwarfs.

Thanks to Hawkins and colleagues, astronomers could soon be finding hundreds more of these dead stars—and at a faster rate, too. That is thanks to a newly developed Artificial Intelligence (AI) powered algorithm developed by the team that has proven to be 99 percent accurate at spotting cosmic graveyards in telescope data.

The algorithm developed by the researchers uses a form of AI called manifold learning to display astronomical objects with similar features in a simplified visual chart. According to Hawkins and colleagues, this technique can then be reviewed for follow-up investigations.

To test the method, Hawkins and his colleagues tasked the algorithm to sort nearly 100,000 white dwarfs cataloged by the Milky Way-mapping Gaia telescope and find the polluted ones.

The algorithm isolated 375 stars that it determined to have multiple tell-tale metals, the name astronomers give to elements heavier than hydrogen and helium, in their atmospheres. Follow-up observations with the McDonald Observatory’s Hobby-Eberly Telescope later concurred with the AI, cementing the discovery of hundreds of elusive polluted white dwarfs.

“Gaia provides one of the largest spectroscopic surveys of white dwarfs to date, but the data is so low resolution that we thought it wouldn’t be possible to find polluted white dwarfs with it,” Hawkins said. “This work shows that you can.”

The AI-powered method could increase the number of known polluted white dwarfs tenfold, in the process also adding to the diversity and geology of known extrasolar planets or “exoplanets,” team co-leader Malia Kao, a graduate astronomy student at the University of Texas in Austin said.

“Ultimately, we want to determine whether life can exist outside of our solar system,” Kao concluded. “If ours is unique among planetary systems, it might also be unique in its ability to sustain life.”

This research is described in a paper published on July 31 in The Astrophysical Journal.

Discussion about this post