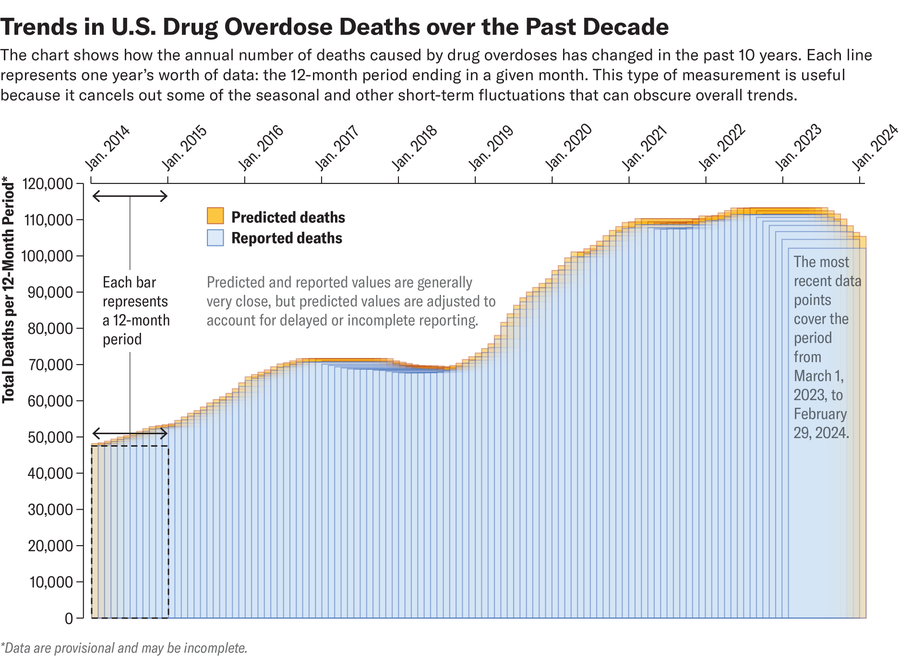

The scale and tragedy of the U.S. opioid epidemic have few comparisons. More than 100,000 people have died of overdoses every year since 2021. Most drug overdose deaths have a single culprit: the extremely potent synthetic opioid fentanyl.

But the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggest that this brutal trend may have crested: overdose deaths have declined slightly overall since last fall, as have overdose deaths from opioids, including fentanyl. It’s too soon to celebrate, however. Deaths over the last 12 months remain incredibly high, at more than 102,000, which is still well above prepandemic numbers: From 2017 to 2019, for example, it’s estimated that more than 68,000 people died every year from overdosing. These recent numbers are provisional and may represent an undercount, according to the CDC.

“It’s definitely too early” to say that deaths have peaked and will continue declining, says Daniel Ciccarone, a professor of family community medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, who studies the social, behavioral and medical dimensions of the opioid epidemic. “We have been to false peaks before.” Nevertheless, he says, “there are a lot of reasons to be, I wouldn’t say optimistic because the numbers are still very high, but to think that we’re making a turn.”

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The reasons for the apparent peak in overdose deaths aren’t fully understood, but experts have a few hypotheses.

One is that overdose deaths are simply beginning to revert to their average level from before the COVID pandemic. Overdose deaths spiked during the pandemic’s first few years. It’s not clear whether more people started using or whether people were simply dying at higher rates; exact counts aren’t available for the number of people who use illicit drugs such as fentanyl. Stress and social isolation increased during the pandemic, which may have led some people to start using or use more frequently or in riskier ways. Treatment for opioid use disorder was also disrupted, and if a person overdosed, it was less likely that someone would be there to intervene.

“Now that the pandemic has largely improved and people are able to go out again, they’re able to socialize. They’re able to access services. That part of the risk has, I think, lessened, and so I think that’s partly why we’re seeing a decrease,” says Magdalena Cerda, an epidemiologist and director of the Center for Opioid Epidemiology and Policy at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine.

Investment in treatment and interventions may be having some effect, she adds. In addition to opioid use disorder medications such as buprenorphine and methadone, access to the overdose-reversing drug naloxone (often referred to by the brand name Narcan) has also increased; the drug is now available over the counter. Additionally, the availability of test strips for detecting fentanyl, as well as other types of drug testing equipment, Cerda says, may have also prevented overdose deaths by making it easier for people who use drugs to avoid fentanyl; the synthetic opioid is much stronger than other opioids and can lead to overdoses at much, much lower concentrations.

A grimmer explanation of these trends is that the population of people who used fentanyl and were at risk of overdosing has simply died off. If there aren’t enough susceptible people, the opioid epidemic will eventually burn itself out like any epidemic, Ciccarone says. The older generation of people who have opioid use disorder is dying, and the younger generation sees how deadly the drugs are and may be less inclined to start using them, adds Jay Unick, an assistant professor at the University of Maryland School of Social Work.

Reduced supply of fentanyl in some parts of the U.S. could be another potential explanation for the decline in overdoses. Most of the illicit fentanyl in the U.S. comes from Mexican cartels, which obtain its precursor chemicals from China and other countries. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency has been cracking down on a Mexican cartel called the Sinaloa cartel, which supplies fentanyl to much of the eastern U.S., and this could be leading to a shortage of the drugs, Ciccarone says. He’s also heard reports recently of a similar fentanyl drought in San Francisco. But fentanyl is incredibly cheap to make and there is no shortage of the precursors required, so Ciccarone doubts that a lack of supply alone can explain the declines in deaths.

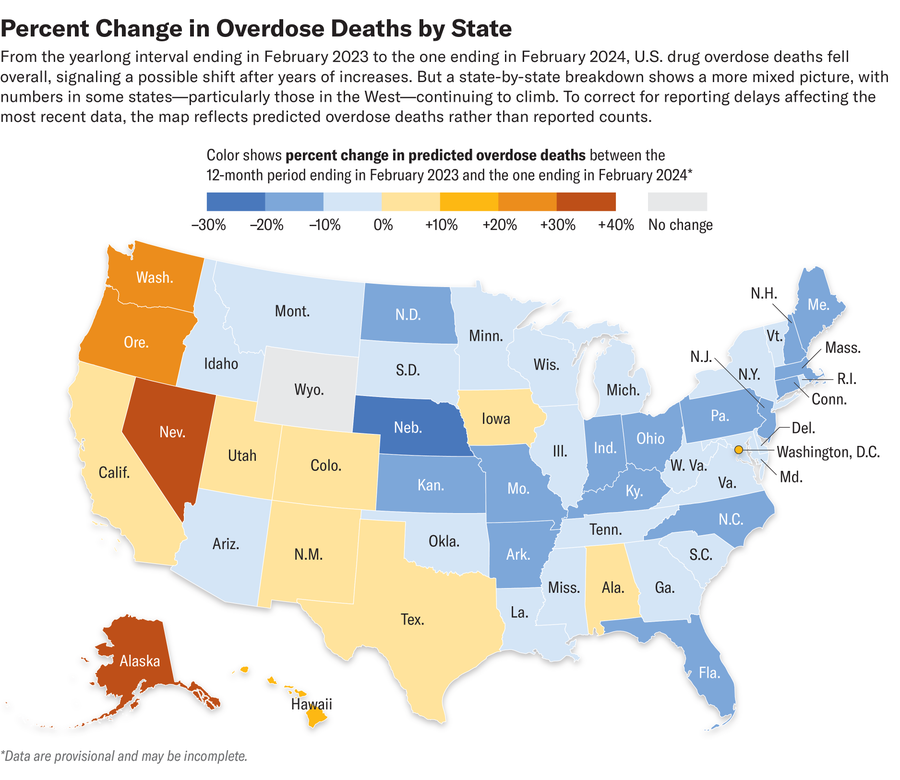

The national trend belies important regional differences: while most eastern U.S. states saw declines in overdose deaths, many western states have seen increases. The timing of fentanyl’s introduction to these areas could explain the divide, experts say. The eastern half of the U.S.—from the Midwest to Appalachia—was first exposed to the drug around 2014, whereas it didn’t really emerge across the West Coast until 2019, Ciccarone says. “We’re late to the party,” he says, adding, “It’s still a deadly party.”

Unick agrees that the timing of fentanyl’s introduction seems the most likely explanation for the East-West differences. “Fentanyl is sort of played out here on the East Coast, but it’s still showing up in places in the West Coast,” he says. The fact that overdoses are starting to flatten or decline nationally is not surprising, he says, but he adds that “these numbers are extraordinarily high.”

The demographics hit hardest by the U.S. opioid epidemic have also shifted: fewer white people are now dying of overdoses, whereas Black and Indigenous people are dying at higher rates. The crisis has also been fueled by homelessness and high rates of mental illness, signs of the compounding effects of income inequality.

The West Coast’s increase in overdose deaths is leading some states to adopt a tougher stance on visible drug use, even in places that previously had softened criminal penalties. In a landmark move in 2020 Oregon voted to decriminalize small amounts of certain drugs, including heroin, cocaine and methamphetamine. But in response to public pressure, the state recently rolled back that policy. It is unlikely that decriminalizing drugs in Oregon caused an increase in opioid overdoses; the increases were also seen in California, Washington and numerous other states that did not decriminalize them.

“There’s not a lot of evidence that it had an effect one way or the other, maybe except in the visibility [of drug use],” Unick says. “It became, like, you’ve got this problem, it’s now more visible, and we’re going to blame this law.”

Even as opioid overdose deaths have gone down overall, deaths involving stimulants such as cocaine and methamphetamine have increased—although many of these involved co-use with opioids. Fentanyl contamination of other drugs has also been reported as a cause of some accidental overdoses. Contamination can occur when midlevel distributors cut fentanyl and cocaine on the same surfaces or equipment without cleaning them, although the fentanyl coming out of Mexico is increasingly pure, and some is shipped in finished pills. And people who use methamphetamine could be exposed to fentanyl accidentally through shared smoking paraphernalia. (Fentanyl is increasingly being smoked in some places.) But Ciccarone thinks the evidence doesn’t support this happening at a large scale. Most people using both fentanyl and methamphetamine are likely doing so intentionally, he says.

Experts express cautious optimism about the overall decline in overdose deaths but noted that we have a long way to go to address the crisis. They call for expanding access to medications such as buprenorphine and methadone, which can safely and effectively be used to wean people off illicit opioids. But the dose of these medications needed to prevent withdrawal symptoms for fentanyl addiction may be higher than what many insurers currently allow. Cerda and others argue that these limits should be raised to effectively treat more people. She also calls for making naloxone more affordable and expanding access to fentanyl test strips, as well as investing more in prevention programs for young people.

“We’re still at the stage where more than 100,000 people are dying a year from overdoses, so the number is still unacceptably high,” Cerda says. “But I am heartened by the persistent decline in overdose deaths in the past few months…, and we should continue to invest in the types of programs that we know work to protect people from dying from overdoses.”

Discussion about this post