It all started in the modern day public square – a podcast recording posted on YouTube.

Though the podcast originally aired almost two years ago, a pair of Indonesian human rights advocates are now fighting defamation charges in a monthslong court trial that began in April.

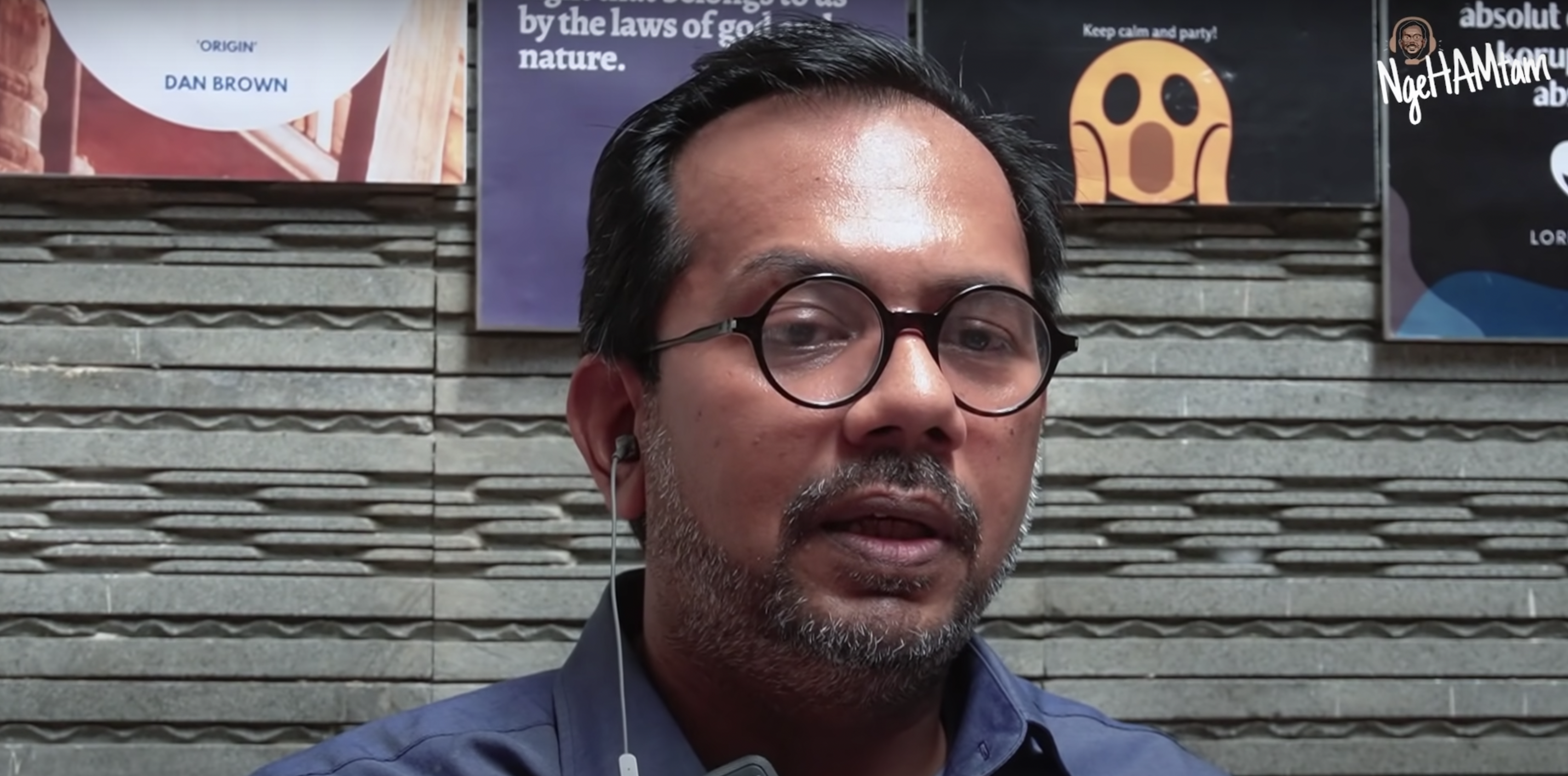

In August 2021, Haris Azhar, executive director of the Lokataru Foundation, and Fatia Maulidiyanti, coordinator for KontraS, published an episode about a report claiming military involvement in the conflicted territory of West Papua was designed to protect mining interests there.

The report was published by a group of 10 nonprofit advocacy groups, including KontraS. Maulidiyanti alleged on the podcast that a government official had a conflict of interest as a shareholder of a mining company in Papua.

The official – Luhut Pandjaitan, the coordinating minister for Maritime and Investment Affairs – disputes this. He filed a defamation complaint in September 2021 under Indonesia’s expansive Electronic Information and Transactions Law (ITE), stating he would “defend my name and that of my children and grandchildren”.

“As far as I know, I have never had a business or started a business in Papua,” Luhut said in court in June, according to the Indonesian newspaper Republika.

Some experts view this case as an example of how the law can help public figures restrict freedom of expression through the legal system.

Indonesia’s ITE law, passed in 2008, is a broad-ranging piece of legislation that regulates areas such as consumer protection and cybersecurity. But a section of the law covering online defamation uses a broader definition than the country’s criminal code, according to some legal scholars, which has driven an increase in accusations under the ITE law that outnumber offline claims.

According to one report, state officials such as heads of government departments and ministers have reported about 35% of all violations of the ITE Law. Many of those reports had to do with defamation.

“The authorities can use [the ITE Law] to silence criticism against them,” said Herlambang Wiratraman, a law professor at Gadjah Mada University in the city of Yogyakarta. “In Indonesia, the regime itself right now has no political intention to prevent the misuse of power like that.”

The case and others like it signify “a turn to authoritarianism” in the country, he said.

Luhut did not respond to an emailed request for comment sent to the ministry or to a message sent to his Instagram account. The case continued Monday with questioning of the director of the coal mining firm PT Toba Sejahtera, who stated that Luhut is still the company’s majority shareholder. The podcast at the centre of the accusations claimed a subsidiary of this company was active in Papua, though Luhut has denied the connection.

Asfinawati Ajub, a defence lawyer for Haris and Fatia who works for the Indonesia Jentera School of Law, said the case could chill other inquiries into official matters.

“I think maybe because he wants [to give] a sign to people, to [the] public: stay away from us,” said Asfinawati. “Even [though] Haris and Fatia will not stop their action, their struggle, but I think maybe some of the activists in the other areas, the remote areas … they will self-censor their thoughts publicly.”

Part of that drive to self-censor could be rooted in the ITE’s broad interpretation.

Eka Putra, a law professor at Jindal Global Law School in India, explained the law is carried out against vaguely defined statements that “harm someone’s honour,” which opens the door to prosecuting even petty insults against powerful officials.

The Indonesian government is especially sensitive to criticism related to Papua, one of the poorest regions of the country with an ongoing separatist movement.

Papuans have reported increased violence and racist attacks in the region. Last year Amnesty International and KontraS called for an independent investigation into the death of a Papuan child allegedly tortured and killed by members of the military. The mining industry in particular has been criticised by human rights groups, calling for an end to the exploitation of the region’s natural resources and alleging widespread corruption.

“This kind of defamation lawsuit is actually distracting from the main problem itself,” said Putra. “Right now, the attention from the public and media is focusing [on the lawsuit]. The bigger problem is the environmental harm [in Papua] and the alleged corruption by a public official.”

Discussion about this post