Food antigens get a lot of negative press because they are the source of allergic reactions to foods such as peanuts, shellfish, bread, eggs, and milk. Even when they don’t lead to allergic reactions, these antigens—along with the many others found in plants and beans—are still considered foreign objects that need to be checked out by the immune system. Ohno and his team have previously reported that food antigens activate immune cells in the small intestines, but not the large intestines. At the same time, some immune cells activated by gut bacteria are known to suppress tumors in the gut. In the new study, the RIKEN IMS researchers bring these two lines of thought together and tested whether food antigens suppress tumors in the small intestines.

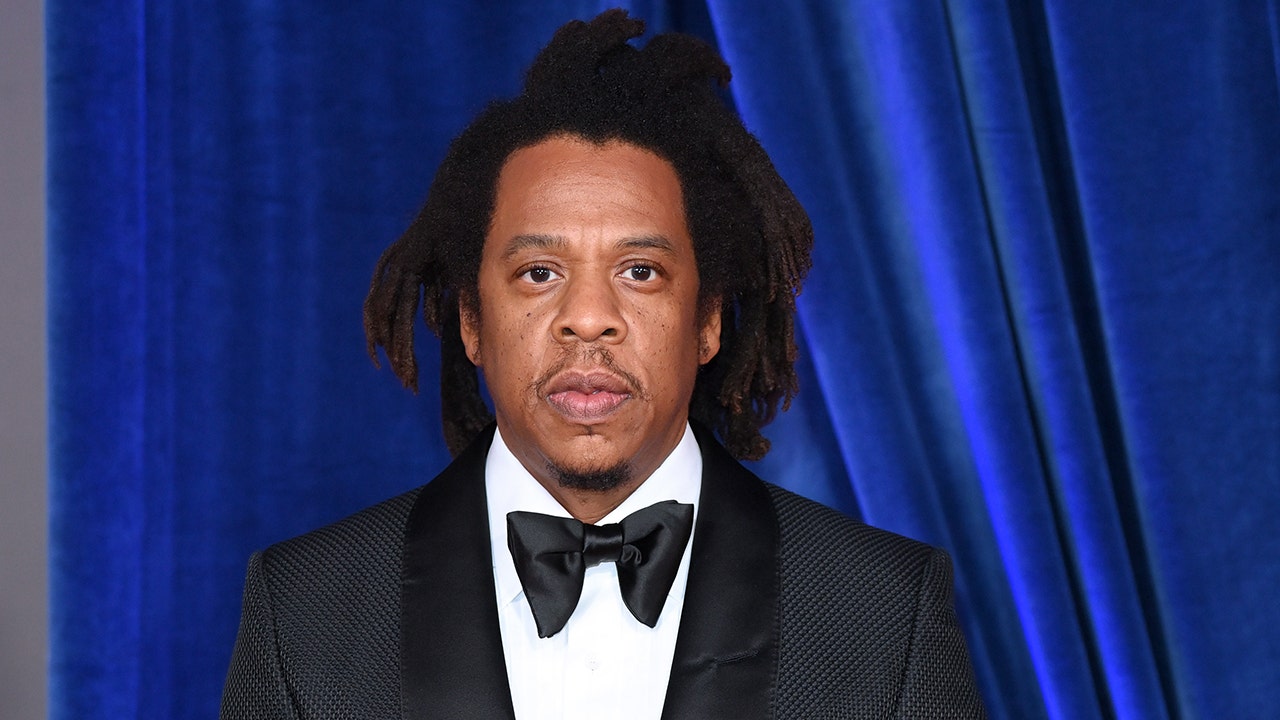

Food antigens help prevent small intestinal (light pink) tumors by making sure we have the right amount of T cells for defense. when mice prone to gut tumors are were given an an antigen-free diet, small intestinal T cells are fewer in number, resulting in more small intestinal tumors.

The team began with a special kind of mouse with a mutation in a tumor-suppression gene. Like people with familial adenomatous polyposis, when this gene malfunctions, the mice develop tumors throughout the small and large intestines. The first experiment was fairly simple. They fed these mice normal food or antigen-free food and found that the ones that got normal food had fewer tumors in the small intestines, but the same amount in the large intestines.

Next, they added a common representative antigen called albumin—which can be found in meat and was not in the normal food—to the antigen-free diet, making sure that the total amount of the protein equaled the amount of protein in the normal diet. When the mice were given this diet, tumors in the small intestine were suppressed just as they has been with normal food. This means that tumor suppression was directly related to the presence of antigen, not the nutritional value of the food or any specific antigen.

The three diets also affected immune cells, specifically T cells, in the small intestines. Mice that got the plain antigen-free diet had many fewer T cells than those that got the normal food or the antigen-free food with milk protein. Further experiments revealed the biological process that makes this possible.

(not mentioned in the article, but described in the paper in details!) When protein antigens are injected into the small intestine of wild-type mice, they are passed to dendritic cells in Peyer’s patches of the small intenstines; similar experiments in M-cell-deficient mice result in fewer dendritic cells receiving the protein antigen.

These findings have clinical implications. Similar to antigen-free diets, clinical elemental diets include simple amino acids, but not proteins. This reduces digestive work and can help people with severe gastrointestinal conditions, such as Crohn’s disease or irritable bowel syndrome. According to Ohno, “small intestinal tumors are much rarer than those in the colon, but the risk is higher in cases of familial adenomatous polyposis, and therefore the clinical use of elemental diets to treat inflammatory bowel disease or other gastrointestinal conditions in these patients should be considered very carefully.”

Elemental diets are sometimes adopted by people without severe gastrointestinal conditions or allergies as a healthy way to lose weight or reduce bloating and inflammation. The new findings suggest that this could be risky and emphasizes that these kinds of diets should not be used without a doctor’s recommendation.

Discussion about this post