Kobe University’s discovery of new PGC-1⍺ protein variants, which are more active during exercise and can regulate fat burning and energy metabolism, suggests a potential breakthrough in treating obesity through increasing energy expenditure rather than merely reducing caloric intake.

New findings highlight PGC-1⍺ variants “b” and “c” as key to improving fat burning and energy metabolism during exercise, offering new avenues for obesity treatment.

Some people lose weight slower than others after workouts, and a Kobe University research team found a reason. They studied what happens to mice that cannot produce signal molecules that respond specifically to short-term exercise and regulate the body’s energy metabolism. These mice consume less oxygen during workouts, burn less fat, and are thus also more susceptible to gaining weight. Since the team found this connection also in humans, the newly gained knowledge of this mechanism might provide a pathway for treating obesity.

The Link Between Exercise and Fat Burning

It is well known that exercise leads to the burning of fat. But for some people, this is much more difficult than for others, casting doubt on whether the mechanism behind losing or gaining weight is as simple as “calories in minus calories out.” Researchers have previously identified a signal molecule, a protein by the name of “PGC-1⍺,” that seems to link exercise and its effects. However, whether an increased amount of this protein actually leads to these effects or not has been inconclusive, since some experiments suggested it while others didn’t.

More recently, the Kobe University endocrinologist Wataru Ogawa as well as other researchers found that there are actually a few different versions of this protein. Ogawa explains: “These new PGC-1α versions, called “b” and “c,” have almost the same function as the conventional “a” version, but they are produced in muscles more than tenfold more during exercise, while the a version does not show such an increase.” His team therefore set out to prove the idea that it is the newly discovered versions, and not the previously known one, that regulate the energy metabolism during workouts.

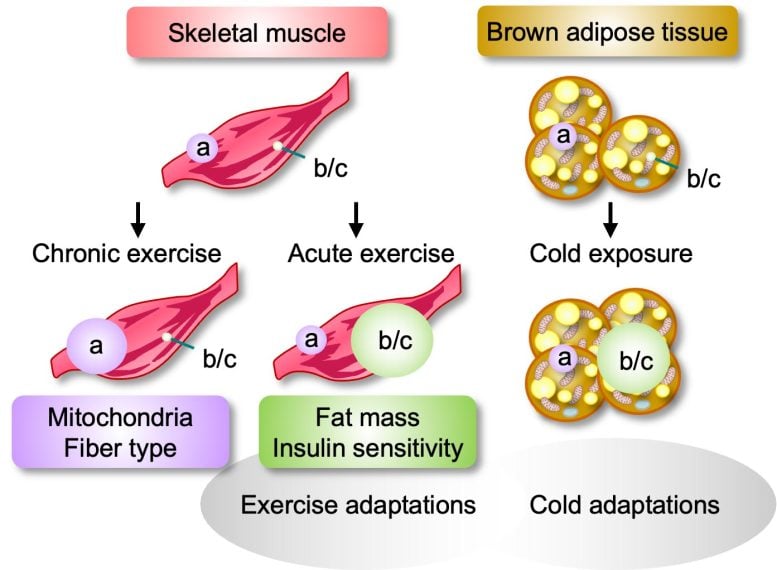

The different versions of the signal molecule PGC-1⍺ react to different stimuli. The standard version (“a”) is produced in response to long-term exercise, whereas the alternative versions (“b/c”) are produced in response to short-term exercise or cold exposure. A lack of these versions makes it harder for affected individuals to respond to these stimuli by burning fat or building muscle mass. Credit: K. Nomura et al. Published by Elsevier GmbH. DOI: 10.1016/j.molmet.2024.101968

To do so, the researchers created mice that lack the b and c versions of the signal molecule PGC-1⍺ while they still have the standard a version, and measured the mice’s muscle growth, fat burning, and oxygen consumption during rest and short-term as well as long-term workout. They also recruited human test subjects with and without type 2 diabetes and submitted them to similar tests as the mice, because

The Kobe University endocrinologist Wataru Ogawa unraveled the physiological role of the different versions of a signal molecule that links exercise and its effects. They found that mice lacking a newly discovered version of the signal molecule that is produced specifically in response to short-term exercise burn less fat than mice that have both versions. Credit: Wataru Ogawa

Long-Term Effects and Cold Tolerance

In addition to the production in muscles, the Kobe University team looked at how the production of the different versions of PGC-1⍺ changes in fat tissues, and found no relevant effect in response to exercise. However, since animals also burn fat to maintain body temperature, the researchers also investigated the mice’s ability to tolerate cold.

Indeed, they found that the production of the b and c versions of the signal molecule in brown adipose tissue is increased when the animals are exposed to cold, and that the body temperature of individuals that cannot produce these versions dropped significantly under these conditions. On the one hand, this may contribute to these individuals’ having more body fat, but on the other hand, it seems to imply that the b and c versions of the signal molecule may be responsible for metabolic adaptations to short-term stimuli more generally.

Potential Treatments for Obesity

Ogawa and his team point out that understanding the physiological activity of the different versions of PGC-1⍺ might allow to devise treatment approaches for obesity: “Recently, anti-obesity drugs that suppress appetite have been developed and are increasingly prescribed in many countries around the world. However, there are no drugs that treat obesity by increasing energy expenditure. If a substance that increases the b and c versions can be found, this could lead to the development of drugs that enhance energy expenditure during exercise or even without exercise. Such drugs could potentially treat obesity independently of dietary restrictions.”

The team is now conducting research to find out more about the mechanisms that lead to the increased production of the signal molecule’s b and c versions during exercise.

Reference: “Adaptive gene expression of alternative splicing variants of PGC-1α regulates whole-body energy metabolism” by Kazuhiro Nomura, Shinichi Kinoshita, Nao Mizusaki, Yoko Senga, Tsutomu Sasaki, Tadahiro Kitamura, Hiroshi Sakaue, Aki Emi, Tetsuya Hosooka, Masahiro Matsuo, Hitoshi Okamura, Taku Amo, Alexander M. Wolf, Naomi Kamimura, Shigeo Ohta, Tomoo Itoh, Yoshitake Hayashi, Hiroshi Kiyonari, Anna Krook, Juleen R. Zierath and Wataru Ogawa, 15 June 2024, Molecular Metabolism.

DOI: 10.1016/j.molmet.2024.101968

This research was funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (grants 26461337, 16H01391 and 15H04848). It was conducted in collaboration with researchers from Tokushima University, the Karolinska Institutet, Kyoto University, Gunma University, the National Defense Academy, Nippon Medical School, the RIKEN Center for Biosystems Dynamics Research and Asahi Life Foundation.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/34/31/3431771d-41e2-4f97-aed2-c5f1df5295da/gettyimages-1441066266_web.jpg)

Discussion about this post