KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— The Supreme Court’s Allen v. Milligan decision should give Democrats at least a little help in their quest to re-take the House majority, but much remains uncertain.

— As of now, the Democrats’ best bets to add a seat in 2024 are in Alabama, the subject of the ruling, and Louisiana.

— It also adds to the list of potential mid-decade redistricting changes, which have happened with regularity over the past half-century.

— The closely-contested nature of the House raises the stakes of each state’s map, and redistricting changes do not necessarily have to be prompted by courts.

Milligan’s ramifications

Landmark U.S. Supreme Court decisions can sometimes be categorized as either beginnings or endings. Take, for instance, a couple of past important decisions that at least touch on the topic of redistricting.

In 1962, the court’s Baker v. Carr decision was a beginning: After decades of declining to enter what Justice Felix Frankfurter described as the “political thicket” of redistricting and reapportionment, the Supreme Court opened the door to hearing cases that argued against the malapportionment of voting districts. A couple of years later, the court’s twin decisions of Reynolds v. Sims and Wesberry v. Sanders mandated the principle of “one person, one vote” be used in drawing, respectively, state legislative and congressional districts, kicking off what is known as the “reapportionment revolution.”

More recently, the court’s 2013 Shelby County v. Holder decision represented an ending: The court threw out the preclearance coverage formula of the Voting Rights Act. Prior to that decision, certain states and jurisdictions (mostly but not entirely in the South) had to submit changes in voting procedures, such as redistricting plans, to the U.S. Department of Justice for preclearance. The court said that this method of determining which places needed preclearance was outdated, and Congress has never mandated a new preclearance formula. So prior to the Shelby County decision, a state like Alabama would have had to have cleared its new congressional district map with the Justice Department. In 2021, it did not have to.

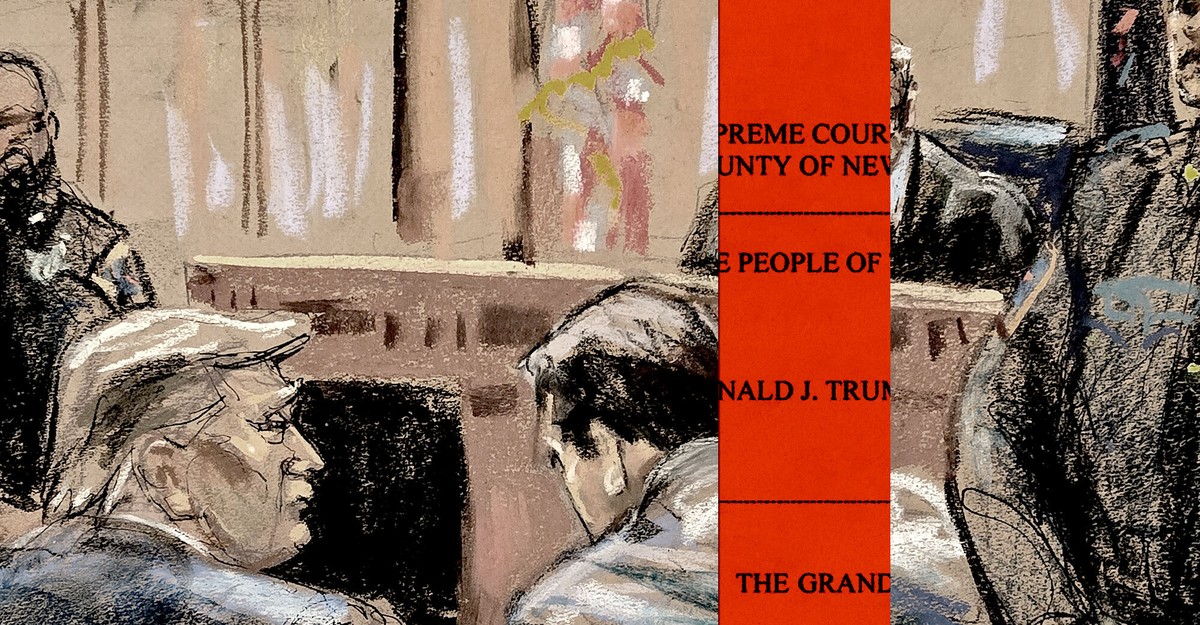

The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Allen v. Milligan last week is neither a beginning nor an ending, although Republican authorities in Alabama and others surely hoped it would represent a form of the latter. Rather, the case is best thought of as a continuation of current law and how the Supreme Court interprets current law — namely, that Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act and the so-called “Gingles test” that undergirds it still exists in the same way we understood them prior to the Milligan decision.

The Gingles test is a three-pronged assessment, laid out as followed in the 1986 Supreme Court decision Thornburg v. Gingles (we’re quoting directly from that decision). These are the conditions that need to be in place in order for a federal court to order the creation of a new majority-minority district:

— “First, the minority group must be able to demonstrate that it is sufficiently large and geographically compact to constitute a majority in a single-member district.”

— “Second, the minority group must be able to show that it is politically cohesive.”

— “Third, the minority must be able to demonstrate that the white majority votes sufficiently as a bloc to enable it… usually to defeat the minority’s preferred candidate.”

Basically, the thing that was surprising about Milligan is that Democrats and their allies thought it was going to be bad for their side to at least a certain degree given the conservative makeup of the court. Instead, the Supreme Court didn’t really change anything.

We are not lawyers, and we will not pretend to be lawyers. Racial redistricting jurisprudence is, to us and likely to many others, confusing. Following discussions with some people who follow redistricting matters on both sides of the political aisle, we’re going to try to assess the fallout from the decision. Let’s start in Alabama and work our way to other states. This is not intended to touch on every single state with potential redistricting legal action that may or may not be impacted by Milligan; rather, we just wanted to hit the highlights of certain states and what the state of play in each is:

— In the Milligan case, a District Court found that Alabama’s congressional map likely violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act by creating a single district where Black voters made up a majority when it should have created two. Alabama is just over a quarter Black, but Black voters constitute a majority of just one of the state’s seven districts (14%). Those who sued over the map persuasively showed that it’s possible to draw a second Black district that satisfies the conditions of the Gingles test. What the actual map will eventually look like remains a mystery, but the likeliest outcome seems to be that instead of Alabama having a single, overwhelmingly Democratic district (the current 7th District, represented by Democrat Terri Sewell), the state seems likely to eventually have two districts that Democrats are favored to win. This is now reflected in our Crystal Ball House ratings — after the decision last Thursday, we tweeted that we were moving one unspecified Alabama district from Safe Republican to Likely Democratic. We say only Likely Democratic because it’s possible that this new district would not be an absolute slam dunk Democratic victory (or perhaps AL-7 would be reconfigured in such a way that it would be borderline competitive).

— A federal court in Louisiana made an analogous ruling in that state, which is politically similar to Alabama. Louisiana is about a third Black, but only one district (the 2nd, held by Democrat Troy Carter) is majority Black, so the state has five Safe Republican districts and one Safe Democratic district. Again, the endgame here very well could be that Democrats end up getting another seat, but we want to see how things play out. Louisiana uses a unique “jungle primary” system, in which all candidates compete together in the same primary, with a runoff required if no one clears 50%. Does that have an impact on the eventual jurisprudence here, or on how a newly-drawn district might perform politically? Or does Louisiana’s system help Democrats, given that because of the jungle primary — which in 2024 will occur concurrent with the November general election — filing deadlines are late in Louisiana, which gives this case extra time to wind through the legal system in advance of the 2024 election. It may be the case that despite Louisiana being similar to Alabama, the Gingles test may not force a second majority-Black district there in the same way as might happen in Alabama — or that is at least what state Republicans want the U.S. Supreme Court to ponder. (Democrats and their allies of course disagree and see Alabama and Louisiana as very similar — that makes sense to us, too, but we shall see.)

— This case also could force changes in Georgia, although it seems possible that a new map there wouldn’t actually change the partisan balance in the state, which is 9-5 Republican following a GOP gerrymander there in advance of the 2022 election. In other words, perhaps a currently Democratic seat in the Atlanta area could be altered to satisfy a court order to add an extra Black seat without actually giving the Democrats an extra seat. Court-ordered redraws do not always lead to changes to the political bottom line: North Carolina Republicans were ordered to redraw their congressional map because of racial gerrymandering concerns in advance of the 2016 election, but they did so in such a way that they were able to preserve their 10-3 statewide majority (we’ll get back to North Carolina later).

— A federal court also ruled against the South Carolina congressional map earlier this year, but it did so in a different way than in the Alabama case. Unlike in, say, Alabama and Louisiana, it might be difficult to satisfy the Gingles test in South Carolina to add a second Black district because of the compactness prong of Gingles: The Black population share in the state is very similar to Alabama, but Black South Carolinians are just more geographically spread out. So when thinking about Milligan’s ramifications, we aren’t including South Carolina in our calculations, based on our best understanding. The U.S. Supreme Court is slated to hear this case in its next term.

— The situation is also different in Florida, where there is ongoing litigation over the partisan gerrymander successfully pushed by Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) last cycle. Among other things, that map undid a Safe Democratic, substantially Black (but not majority Black) district that ran from Jacksonville to Tallahassee. The state Supreme Court in Florida may order that district restored in some form — although the court is fairly aligned with DeSantis, so we wouldn’t necessarily bet on it — but, if it does, the court’s decision would be based on particulars in the state constitution, amended by voters in 2010 to prevent gerrymandering, as opposed to federal law (Democratic analyst Matt Isbell had a good rundown of the situation there if you’re curious).

— Texas also comes up in discussions of the ripple effects of the Milligan ruling, but the situation there is more complicated in part because the discussion is more about Latino voters than Black voters, and Latino voters are not as politically cohesive as Black voters are — which, again, may complicate a court using the Gingles test to force a redraw there.

So what’s the upshot here? Again, and we have to stress this even though it’s an answer that won’t satisfy anyone, we are just going to have to wait to see how things shake out. But we do think some of the post-Milligan analysis that suggested that Democrats could enjoy a windfall of several seats in time for the 2024 election is, at the very least, premature. That may happen, eventually, but at the moment we’re most focused on the likelihood of a single extra Democratic seat in Alabama (which is now reflected in our ratings) and quite possibly Louisiana (which is not reflected in our ratings, at least for now).

One other thing to remember — just because Democrats got a ruling that they liked here does not mean that this very conservative court is going to start ruling for them on related cases in the future. As others noted, the key vote in this 5-4 decision was probably Justice Brett Kavanaugh, who left some breadcrumbs suggesting that Alabama just did not make the right arguments in this case. This is part of the reason why we are not making a ton of assumptions right now about what is next in states beyond Alabama.

Speaking of future Supreme Court decisions, Milligan was not the only important redistricting-related case in front of the court this term: We are still waiting to see what the Supreme Court says in Moore v. Harper.

That case is about the North Carolina state Supreme Court’s intervention against a Republican gerrymander in advance of the 2022 election. That intervention turned what would have been a 10-4 or even 11-3 Republican map in North Carolina into what became a 7-7 tie in November 2022, saving the Democrats several seats. Since then, Republicans have taken control of the North Carolina court, which already overruled its previous decision that defanged Republican gerrymandering efforts. So Moore v. Harper appears very unlikely to have any practical bearing now on North Carolina itself: Republicans are going to have the power to restore a gerrymander there.

The importance of the case from a redistricting perspective, then, is whether the U.S. Supreme Court will impose constraints on state judicial interventions against congressional maps. We have no idea what the court is going to do — it might just punt the decision given that North Carolina’s Supreme Court reversed itself after it changed from Democratic to Republican in 2022. However, the U.S. Supreme Court may issue a decision that impacts the ability of other state courts to intervene against gerrymandering. That could have ripple effects, like in Wisconsin, where the state’s new, Democratic-leaning state Supreme Court may be tempted to rule against Republican partisan gerrymanders later this year. Stay tuned.

Conclusion

Since the Supreme Court’s aforementioned Wesberry v. Sanders decision, which applied the concept of “one person, one vote” to congressional redistricting, there have been 30, two-year congressional election cycles (every even-numbered year from 1964 through 2022). Based on research I did for my history of recent House elections, 2021’s The Long Red Thread, at least one congressional district (and often more) changed from the previous cycle in 23 of those 30 election cycles. Most of these changes (though not all) were forced by courts. The 2024 cycle will make it 24 of 31 cycles, with potentially several states changing their maps in response to court orders. We bring this up to say that despite the now-familiar rhythm of all the states with at least two districts redrawing to reflect the census at the start of every decade, it’s common for at least some districts to change more often than that.

Beyond the states mentioned above, at least some of which will have new maps next year, Ohio is also likely to have a new map that quite possibly will be better for Republicans than the current one, which the Ohio Supreme Court ruled unconstitutional but which was eventually used anyway in 2022 (just like in North Carolina, the Ohio Supreme Court has since changed in such a way to make it more amenable to GOP redistricting prerogatives going forward). Democrats in New York are trying to force a new map, in part because of changes to that state’s highest court that may make that court more amenable to Democratic redistricting arguments than the previous court, which undid a Democratic gerrymander. The particulars in both states require longer-winded explanations that we’ll save for another time.

And aside from the changes forced by courts, one also wonders if we will eventually see a redistricting technique that at one time was common but really has not been in recent decades: a state legislature enacting an elective, mid-decade remap without prompting by the courts.

The most famous modern example of this is when Texas Republicans redrew their state’s congressional map following the 2002 election. That gerrymander, which is most closely associated with former House Majority Leader Tom DeLay (R), came after Republicans took full control of Texas state government in 2002. They replaced a court-drawn map that reflected a previous Democratic gerrymander and imposed their own partisan gerrymander, turning a 17-15 deficit in what had become a very Republican state into a 21-11 advantage. Georgia Republicans did something similar later in the decade, though to much less effect; Colorado Republicans tried to but were blocked by state courts — some states do not allow mid-decade redistricting, but others do (there is no federal prohibition on mid-decade redistricting). North Carolina’s looming redraw is somewhat similar to those in Texas and Georgia from the 2000s: The voters changed the political circumstances — Republicans taking control of Texas and Georgia state government in 2002 and 2004, respectively, and Republicans flipping the North Carolina Supreme Court in 2022 — paving the way for the partisan gerrymanders that did (or will) follow.

The redistricting stakes are extremely high at a time when U.S. House majorities are so narrow. Democrats won just a 222-213 majority in 2020, and Republicans won the same 222-213 edge last year. It’s possible that the net impact of mid-decade redistricting — including some of the changes we’ve laid out above — could be decisive in who wins the majority next year. It may also prompt other states to try to go back to the redistricting well without prompting by courts — and if they determine they can based on state law — if they believe that new maps could make a difference in determining majorities.

Discussion about this post