When I was in high school and university, every Wednesday afternoon required to the Rexall drug store in my small prairie hometown. That was the day any new music magazines appeared in the racks. Using money I earned stocking shelves in the local grocery store, I’d grab the latest editions of Rolling Stone (which came out every two weeks), and monthlies like CREEM, Trouser Press, and Circus for international news, and Music Express to learn about what was happening in Canada.

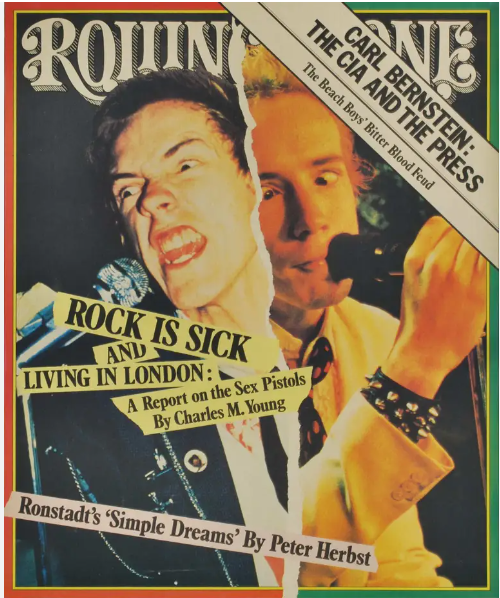

My parents were appalled, of course, at what they considered a waste of money. And when I brought home the infamous Rolling Stone issue — “Rock is Sick and Living in London” — featuring the Sex Pistols on the cover (a newsstand sales disaster for the magazine in October 1978), my parents openly wondered if I needed to be institutionalized for my own good.

Rolling Stone Cover 17 Oct 1978.

My music magazine habit only got worse over the decades. Occasionally, I’d see a copy of Melody Maker or The NME — horribly outdated by the time they arrived in Canada — in a specialty bookstore and grab them for a look at the oh-so-exotic scene in the UK. When Chapters and Indigo arrived with their giant selection, my spending on music magazines grew to several thousand dollars a year.

By this time, there was also Alternative Press, Raygun, Option, Shift, Maximum RocknRoll, and Modern Drummer all from the U.S. with domestic backfill from Canadian Musician, Chart Attack, and Graffiti. I bought them all, all the time. But most of my cash went to British publications.

There were so many great magazines from the U.K., especially in the late 1990s — Q, Select, Vox, Mojo, Record Collector, Uncut, The Word, The Face, Smash Hits, Sounds, Kerrang — and a bunch of others I know I’m missing. I hoovered them up every month, storing back issues carefully on shelves in the basement. This formed an indispensable research archive for my Ongoing History of New Music radio show.

How could the British support so much music journalism? A lot had to do with the role the music press had carved out for itself since at least the 1950s. With BBC radio refusing to play or cover popular music beyond a few hours a week — too lowbrow for the Beeb — print was the only place to learn about The Beatles, The Stones, Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple, Eric Clapton, and all the great U.K. stars. Yes, there were private broadcasts from Radio Luxemburg and pirate stations like Radio Caroline, but if you wanted your music to be covered in-depth, you needed the weeklies and monthlies.

British publications became not just information sources, but arbiters of taste, anointers of stars, and laid waste to acts that bored them. They also believed it was their solemn duty to push music culture forward by identifying (and often inventing or outright fabricating) new scenes and sounds. The weeklies, NME and Melody Maker, were very good at this, each in its own way. Folk, trad jazz, folk, psych, glam, punk, ska, rockabilly, New Romantics, C-86, acid house, rave, shoegaze, Madchester, Britpop — none would have flourished as they did had it not been for the coverage and occasional fictions created by British music magazines.

Alas, though, the golden age for music magazines has passed. With the rise of the internet, it was no longer necessary to wait for a magazine to tell you what was happening. Circulation dropped precipitously. Meanwhile, declining physical record sales meant a fatal drop in advertising by record labels. Margins shrank and then disappeared. Experienced staff saw story commissions dry up and were eventually laid off. Ownership was consolidated and razor-sharp focus on writing and interviews suffered. Bloggers and streamers became the new influencers.

Outside of Mojo and Record Collector, there are precious few physical publications I still buy, although often with misgivings. Don’t the publishers realize that those of us who still buy physical magazines don’t have the eyesight we once did? Why is so much of each issue in six-point fonts?

So many once-great and bloody essential magazines have gone out of business. Graffiti was gone by 1986. Sounds became extinct in 1991. It became impossible to get Music Express after Christmas 1996. Vox disappeared in the summer of 1998. Having stood on its own since 1926, Melody Maker was folded into rival NME in 2001 with Select ceasing publication around the same time. Smash Hits died in 2006. Q, which underwent at least half a dozen re-launches in a bid to survive, finally gave up the ghost in 2020.

Some have transitioned to online. There might still be physical editions of Rolling Stone and Alternative Press — that will tell you how long it’s been since I’ve looked at a magazine rack — so I dip in from time to time whilst browsing.

But there are a couple of reasons to be optimistic. Online subscriptions are far cheaper than having issues mailed to you, especially from overseas. Information arrives regularly and promptly, not two or three months out of date. And it can be immeasurably more convenient to take a bunch of reading material on an iPad for a long flight.

And there are signs of physical life. Kerrang keeps the faith as a quarterly. CREEM magazine is also back as a four-times-a-year publication that, boy howdy, is as irreverent as issues of old. Meanwhile, after five years of being online-only, The NME has returned as a print publication this summer with a promise of six issues a year. And Mojo and Record Collector seem to be in it for the long haul.

Oh, and that archive of old magazines in my basement? They became a fire hazard and a potential city for rodents, so I pawned them all off on a guy who ran a used record store. I see now that was a mistake because many issues are now coveted by collectors. That includes my old “Rock is Sick” edition of Rolling Stone. I just saw it up for auction with an asking price of US$770.

—

Alan Cross is a broadcaster with Q107 and 102.1 the Edge and a commentator for Global News.

Subscribe to Alan’s Ongoing History of New Music Podcast now on Apple Podcast or Google Play

© 2023 Corus Radio, a division of Corus Entertainment Inc.

![Dipika Kakar breaks down, Usha Nadkarni shares her culinary struggles [Watch promo] Dipika Kakar breaks down, Usha Nadkarni shares her culinary struggles [Watch promo]](https://st1.bollywoodlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Celebrity-MasterChef-Dipika-Kakar-Usha-Nadkarni-1.jpg)

Discussion about this post