KEY POINTS FROM THIS ARTICLE

— After North Carolina’s then-Democratic state Supreme Court blocked a GOP congressional gerrymander last cycle, the new court re-opened the door to a Republican gerrymander for 2024.

— A new map that legislative Republicans approved yesterday could up their advantage in the state’s currently evenly-divided 7-7 delegation to 11-3.

— Assuming the new map stands, we are moving three Democratic-held seats to Safe Republican while leaving Rep. Don Davis’s (D, NC-1) contest as a Toss-up.

Table 1: Crystal Ball House rating changes

A new version of an old gerrymander

Over a decade ago, as the post-2010 round of redistricting was on the horizon, the Washington Post called North Carolina the GOP’s “Golden Goose” of redistricting. In 2010, North Carolina’s House Democrats weathered a tough election cycle to maintain a 7-6 edge in their marginal state’s congressional delegation — that map had been a Democratic gerrymander. But lower down the ballot, Republicans took control of both chambers of the state legislature. In a state where the governor plays no role in redistricting, Republicans put an aggressive gerrymander in place for 2012 — on a 13-seat map, it created 10 John McCain-won seats. Though the gerrymander didn’t immediately work as intended (one Democrat held on in a GOP-leaning seat in 2012) Republicans achieved their desired 10-3 split in the 2014 elections.

Since then, because of court intervention, North Carolina’s congressional map has been redrawn no fewer than three times. For 2022, the state Supreme Court, which had a Democratic-aligned majority at the time, rejected a GOP-drawn map to impose its own plan. As the state gained a seat in the 2020 census, the court-drawn plan would have given Joe Biden and Donald Trump seven districts apiece. In last year’s midterm elections, that 7-7 partisan split materialized. But, importantly, the state Supreme Court’s remedial plan was only meant to be used in 2022.

In many ways, 2022’s result in North Carolina was an echo of 2010: while Democrats fared well in House races, the lower-ticket races were better for Republicans. Aside from maintaining control of the legislature, Republicans flipped the state Supreme Court. With that, legislative Republicans were set to draw a new map with a freer hand. As Map 1 shows, Republicans brought out their golden goose again.

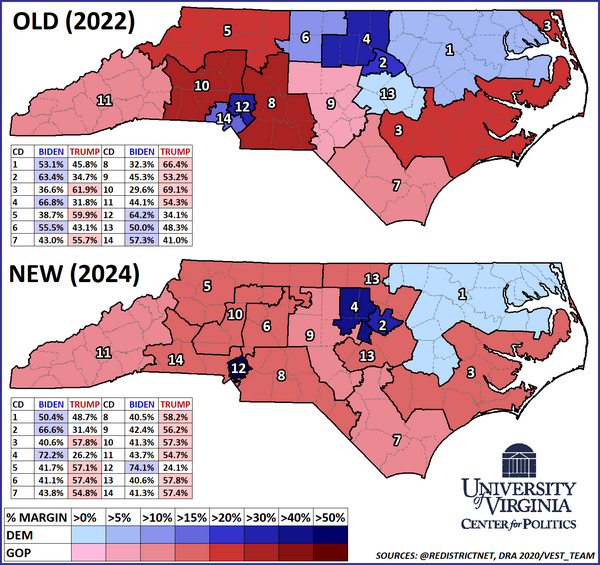

Map 1: Old vs new North Carolina districts by 2020 presidential vote

One of the biggest questions going into this remap was how Rep. Don Davis’s (D, NC-1) district would be reconfigured. In the Supreme Court’s Milligan decision earlier this year, the high court sanctioned the creation of a second Black-majority district — “or something close to it” — in Alabama, and that may eventually lead to another such district being drawn in Louisiana and perhaps elsewhere. While it is possible to draw a Black-majority district in northeastern North Carolina, Davis’s district retains a white plurality, as the Black share in his district falls slightly, from 41% to 40%.

Compared to the outgoing plan, Davis’s district, while retaining its basic location, moves south and east. Two of the most notable additions to the new NC-1 are along the coast: The district picks up the pair of Camden and Currituck counties and now takes in all five “Finger Counties” that make up the state’s northeastern corner. Historically Democratic — losing statewide Democrats were competitive there into the early 2000s — the two counties have seen an influx of retirees and have almost become exurbs of Virginia Beach. Under the outgoing, court-drawn plan, the 1st District included almost all of Greenville’s Pitt County, a Biden +9 county that was the most populous in the district. The redrawn NC-1 avoids Pitt County entirely.

The effect of the changes is that NC-1 becomes a more marginal seat. Biden would have carried Davis’s current district 53%-46%, and although the new seat would have still backed Biden, his 50%-49% margin there now puts NC-1 right of the national popular vote. Broadly, the trends in northeastern North Carolina have not been positive for Democrats. In 2010, as North Carolina saw its most lopsided Senate race in decades, Sen. Richard Burr (R) was reelected by about a dozen points but lost the new NC-1 by three points. Last year, as now-Sen. Ted Budd (R) won Burr’s open seat by three points, he would have carried the new district 52%-46% over former state Supreme Court Chief Justice Cheri Beasley (D).

To win his current seat, Davis, who was then a state senator, ran just over four points better than Beasley — as she carried the outgoing seat by half a point, he won by 4.7%. So it stands to reason that, assuming a uniform swing, Davis would have lost last year under the new lines. Still, we are keeping the seat a Toss-up. Davis now has incumbency and it’s possible minority turnout — which lagged throughout the South last year — could be stronger next year. North Carolina Republicans also have more of a farm team in this area than they did just a few years ago, but we’ll wait and see who emerges from their primary.

Aside from NC-1, the new map features three Biden-won seats — unlike NC-1, each has an ironclad Democratic lean. In the Research Triangle area, Rep. Deborah Ross (D, NC-2) keeps a district that is entirely confined to Wake County (Raleigh). Just to the west, the pair of Durham (Duke) and Orange (UNC Chapel Hill) continues to make up the majority of first-term Rep. Valerie Foushee’s 4th District. The third Democratic sink is in the Charlotte area, as Rep. Alma Adams (D, NC-12) is given a Biden +50 seat that is entirely within Charlotte’s Mecklenburg County (her previous district took in much of neighboring Cabarrus County).

As the Crystal Ball has long expected, the proverbial “odd members out” in this remap were Democratic Reps. Jeff Jackson, Wiley Nickel, and Kathy Manning. Before today, we had all three of their districts parked in the Toss-up category, as sort of a placeholder rating in anticipation of a new map.

Jackson (D, NC-14), a prolific fundraiser who has become known for his savvy use of social media, has been drawn into NC-8, a red seat that takes in the eastern Charlotte metro area. Jackson has long been rumored as a potential candidate for state Attorney General (the current Democratic incumbent, Josh Stein, is running for governor), so the remap seems likely to nudge Jackson further in that direction. On a similar note, NC-8 is an open seat because its current occupant, Rep. Dan Bishop (R), is seeking the GOP nod for state Attorney General.

Jackson’s 14th District is now a western Charlotte-metro seat that seems drawn for state House Speaker Tim Moore (R). Before 2022, Republicans tried to draw a similar seat that seemed designed for Moore, but then-Rep. Madison Cawthorn (R, NC-11) announced he’d run in that new seat to spite Moore — but that map was never used and Cawthorn lost his own primary to now-Rep. Chuck Edwards (R, NC-11).

If they run for reelection, neither Nickel nor Manning have promising options, assuming this map stands. Last year, Nickel won a close contest in the 13th District, which was, at the time, the most marginal district in the state. Legislative Republicans removed many of the 13th’s urban, and more Democratic-leaning, Wake County precincts. As the seat is now an almost entirely exurban seat, Biden’s 2020 share in the district dropped from 50% to 41%. Though Nickel is waiting to see how litigation plays out before he announces his plans, under this map, it is possible that he could challenge Ross in the primary — his home precinct is in the 2nd District (as it is, he does not live in the outgoing 13th).

In the Greensboro area, Manning’s home base of Guilford County has been cracked three ways. Manning could run in her current district’s numerical successor, although the redrawn NC-6 is now the reddest of the three Guilford County seats. Former Rep. Mark Walker (R, NC-6), who was drawn out in a pre-2020 remap, is reportedly ditching his underdog gubernatorial campaign to run in the new NC-6. Districts 5 and 9 are held by GOP incumbents Virginia Foxx and Richard Hudson, respectively — we may note that the latter is the chairman of the National Republican Congressional Committee. All three Greensboro-area districts would have given Trump between 56% and 58% in 2020.

Speaking more broadly, Manning’s predicament illustrates why the new map seems likely to be an effective gerrymander. On the outgoing, court-drawn map, four districts would have given Trump more than 60% of the vote. Republicans unpacked those districts while stuffing Democrats into three safe seats. As a result, Biden’s share in the 10 Trump-won districts is more than 40% but less than 45% — in other words, enough to give Democrats a solid base of support but not enough to get to a majority. In 2020, Gov. Roy Cooper led the Democratic ticket and won reelection by nearly five points. But he would not have carried any of the Trump-won seats on the new map.

Any of the Trump-won seats on the new map would be redder than any of the seats House Democrats currently hold. Looking longer-term, Democrats’ best opportunity may be NC-11, which makes up the western tip of the state — there have been some pro-Democratic shifts in the Asheville metro area. Though NC-7, in the southeastern corner of the state, is slightly more Democratic on paper, it has been drifting towards Republicans. Both districts 7 and 11 saw relatively minor changes for this remap and would have each given Biden about 44%. Still, the fact that they are now the weakest Trump-won districts in the state speaks to how tough the rest of the map is for Democrats.

While we’ll monitor what the displaced Democratic incumbents end up doing, we feel comfortable enough moving all three of their seats into the Safe Republican category. This gives Republicans three fairly certain pickups, and they could very possibly win a fourth, if they defeat Davis.

On our updated House ratings, Republicans now have 214 seats at least leaning to them, Democrats have 204, and there are 17 Toss-ups. The redistricting battles are not over, though, and Democrats have a chance to potentially gain a seat apiece in Florida and Louisiana based on separate, unrelated legal matters in those states. There is also the ongoing saga of New York redistricting, which hypothetically could help Democrats regain lost ground there, as well as some other redistricting loose ends that we will be monitoring.

Discussion about this post