A decade ago, scientists at the European Space Agency (ESA) had just wrapped up the yearslong process of building a comet-chasing spacecraft named after the Rosetta Stone, the key to deciphering ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics. The scientists hoped the Rosetta mission would similarly reveal new clues about how our pocket of the universe assembled itself roughly 4.5 billion years ago.

To do so, the mission’s goal was to study an otherwise-unremarkable comet called Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, a 2.5-mile-wide (4 kilometers) frozen rock left over from the formation of the solar system. Following a decade-long journey, Rosetta arrived at its target in August 2014.

Just a few hours after the spacecraft arrived, scientists celebrated the first close-up photos of the comet radioed home by Rosetta and its lander, Philae. Mark McCaughrean, a senior scientific adviser at ESA, called those first snapshots “a scientific Disneyland.”

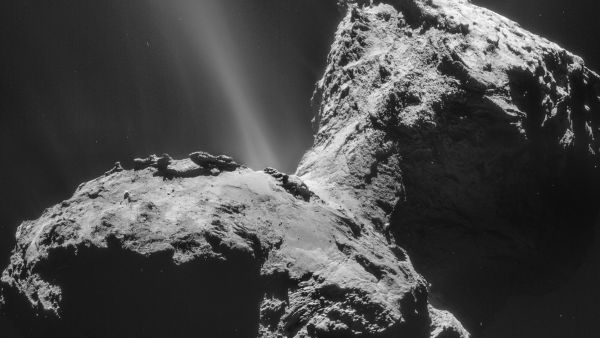

Exploring that cosmic wonder led to so many notable Rosetta discoveries that scientists find it difficult to pick the best one. From revealing the comet’s rubber-ducky shape and unique auroras up close to discovering Earth-like gases streaming from the comet, Rosetta’s data contained precious information about how the cosmic fossil — and the solar system — took shape billions of years ago, which thrilled scientists and fueled many careers.

Related: Photos: Europe’s Rosetta comet mission in pictures

“Rosetta is one of the most ambitious and challenging missions, also from a human perspective,” Claire Vallat, who was involved in planning the mission, said in a statement. “It was a long project involving people spread all over the world, sometimes belonging to different generations, all learning to work together towards a common scientific goal.”

To celebrate the 10th anniversary of Rosetta’s arrival at Comet 67P — the first comet that a spacecraft orbited and landed on — scientists who were involved with the mission recalled what it was like to see those first images arrive, notable scientific findings and other behind-the-scenes looks at the mission.

A “rubber duck” rock

Shortly before Rosetta arrived at Comet 67P, its onboard cameras saw the distant dot it was hurtling toward transform into a 2.5-mile-wide rock, which the mission team quickly parsed into a short video. “It suddenly became very real,” Nick Thomas, who was on the mission’s camera team, said in an ESA recent statement.

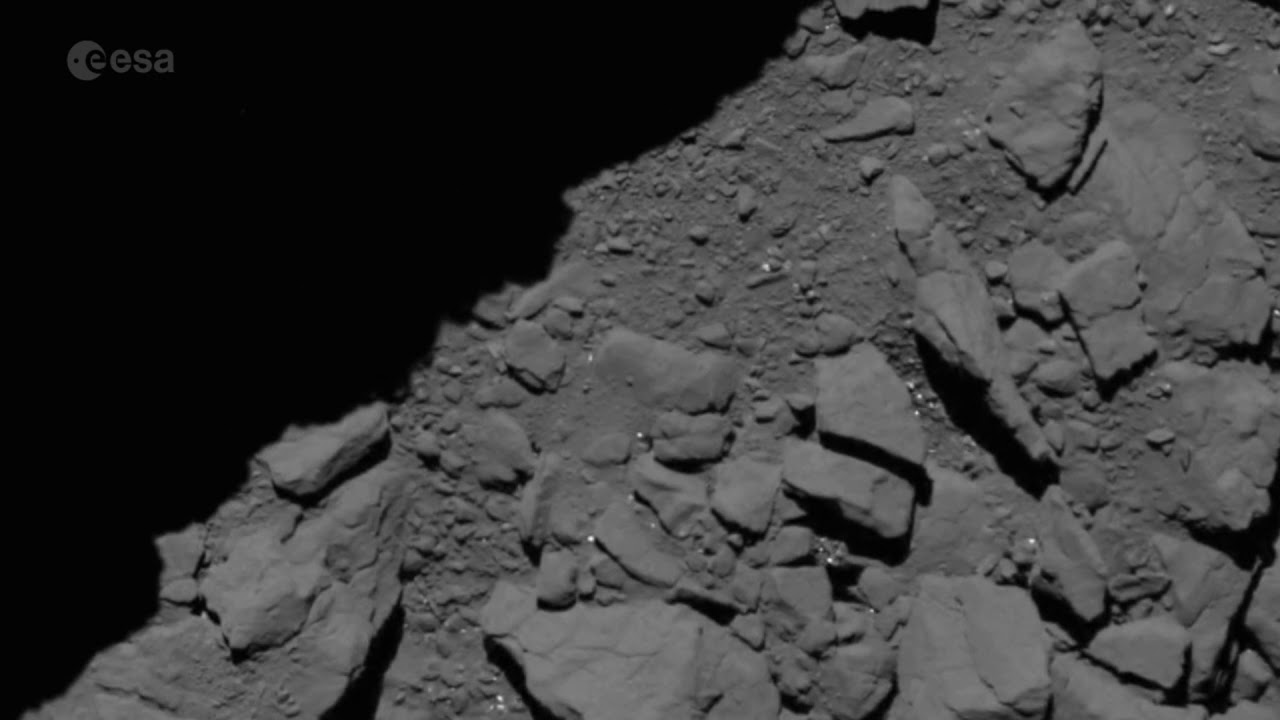

Those first detailed images showed Comet 67P to be nothing like the potato-shaped rock the scientists had long expected. Instead, the comet was a two-lobed “rubber ducky” — the result of two full-fledged comets colliding at low speeds in an infant solar system — with “goose bump” rocks that were the comet’s building blocks.

“That was staggering,” Thomas said. “It told us we were there and we were going to find something special.”

The images are special to many scientists involved with the mission, but they are especially memorable for two who were on vacation when the close-ups radioed in.

“I had no internet access,” recalled Geraint Jones, who is now a project scientist for the BepiColombo mission to Mercury. “So I actually saw the shape of the comet for the first time on a newspaper stand in Germany!”

“This was a very exciting moment, since the nucleus shape did not look at all like how we envisaged it until then,” added Vallat, who also was on vacation and remembers frantically checking her phone for any new images Rosetta might have sent home.

Mysteries and discoveries

Comet 67P was headed toward the inner solar system during the Rosetta mission. So the probe was tasked with rendezvousing with the comet when it was still in the frigid pockets of our solar system and with watching how the icy rock transformed as regions cast in darkness for years became flooded with sunlight.

“We see comets in the sky and know they’re our nearest neighbors,” Thomas said. “We’re naturally nosy; we want to meet our neighbors and have a look at what they’re doing.”

Over the year, Rosetta recorded up to two bathtubs’ worth of water vapor and 2,200 pounds (1,000 kilograms) of dust escaping the comet’s surface every second, all of which formed its signature, 62-million-mile-long (100 million km) tail. “It’s like throwing paint into a stream and the paint mixes with the water,” Jones said. “Rosetta sitting in this flow was a very important part of the mission; it informed our understanding of how comet plasma tails form.”

In that stream, Rosetta found lots of organic material and other data that revealed that a few noble gases in Earth’s atmosphere come from comets, leading to the hypothesis that a flux of comet impacts may have graced Earth with life-boosting ingredients. Perhaps counterintuitively, the probe found the composition of the water vapor on Comet 67P was significantly different from Earth’s, leaving scientists none the wiser about how our planet’s oceans flourished.

Scientists have also puzzled over why the comet’s interaction with the solar wind, particularly via a powerful outburst, created a larger-than-expected void of the solar magnetic field. The only other time such a phenomenon was seen was in 1986, around another comet.

“It actually became the focus of my Ph.D. to analyze the Rosetta data and find out why this ‘cavity’ was so much bigger than expected,” said Charlotte Götz, a scientist at Northumbria University in England who was involved with the discovery.

Another unexpected finding was how much the comet’s activity dimmed when ejected dust returned to the surface. “There are places that you would expect to have been affected by the same heat and radiation from the sun, but the surface texture is totally different,” Thomas said.

Onward and upward

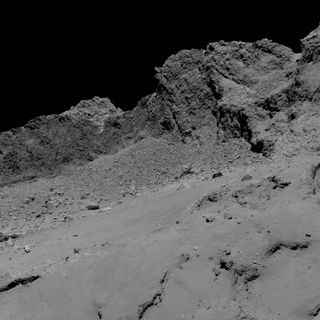

After more than a decade in space and two years of studying Comet 67P, the Rosetta spacecraft smashed into its cosmic companion on Sept. 30, 2016, as intended, in an epic mission finale. Heading in, the probe sent home increasingly close-up images of the comet (and heartbreaking goodbye tweets), offering scientists rare front-row views of the comet’s surface and an ancient pit that would become Rosetta’s final resting spot.

Rosetta’s final image — a blurry snapshot of its impact site, named Sais after an ancient town where the Rosetta Stone was originally located — lives in the digital archives as a testament to the engineers and scientists who successfully built and operated the mission for over 20 years.

“We were part of an intense, exciting adventure which was not only achieving a series of firsts but also realizing the dreams of many people whose entire careers were for the most part dedicated to Rosetta,” said Patrick Martin, who was the mission manager and is now part of the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter mission.

In 2021, Comet 67P made its closest approach to Earth in 200 years. The space rock may be speeding away from our planet ferrying two defunct robotic passengers, but its historic cruise alongside the comet provided scientists with enough data to scout for years. In fact, one of the most exciting discoveries from the mission, a unique type of ultraviolet aurora seen for the first time on a comet, came four years after the mission ended.

“This leads to discoveries that are not immediately obvious,” Götz said. “For me the post-mission phase never ends. We’re always trying to improve things, and the really exciting science happens in the years after. There’s still so much data that we haven’t really looked at.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d1/82/d18228f6-d319-4525-bb18-78b829f0791f/mammalevolution_web.jpg)

Discussion about this post