Using evolution as a guiding principle, researchers have successfully engineered bacteria-yeast hybrids to perform photosynthetic carbon assimilation, generate cellular energy and support yeast growth without traditional carbon feedstocks like glucose or glycerol. By engineering photosynthetic cyanobacteria to live symbiotically inside yeast cells, the bacteria-yeast hybrids can produce important hydrocarbons, paving new biotechnical pathways to non-petroleum-based energy, other synthetic biology applications and the experimental study of evolution.

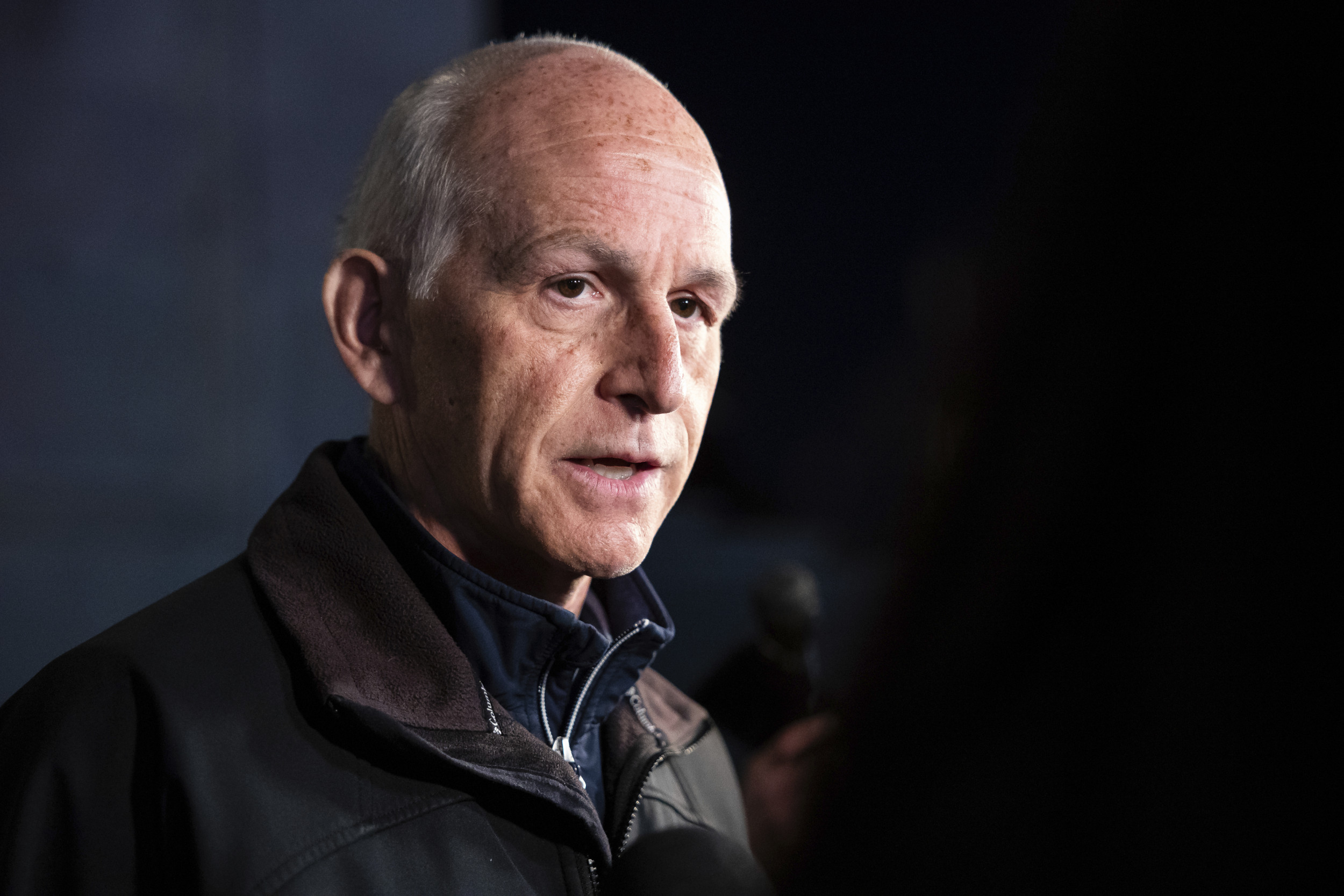

“All cells that have a nucleus also house a variety of organelles — such as mitochondria and chloroplasts — which perform specific functions and contain their own DNA,” said University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign chemistry professor Angad Mehta, who led the all-Illinois research team. “Researchers had long theorized that complex life forms got their start when one of these types of cells fused with another in a process called endosymbiosis.”

In a previous study, Mehta’s team showed that lab-generated cyanobacteria-yeast chimeras, or endosymbionts, can supply photosynthetically generated ATP to the yeast but don’t provide sugars. In the new study, the team engineered cyanobacteria to break down sugars and secrete glucose, then combined them with yeast cells to create chimeras that can grow in the presence of CO2, using the sugar and energy produced by the bacteria.

The study findings are published in the journal Nature Communications.

Armed with the ability to engineer a non-photosynthetic organism into a photosynthetic, chimeric life form, the team focused their research on determining how these chimeras could be used to bioengineer new metabolic pathways capable of producing valuable products like limonene, a simple hydrocarbon compound found in citrus fruits, under photosynthetic conditions.

“Limonene is a relatively simple but important molecule with a large market,” said Mehta, who is also affiliated with the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology. “This proof-of-concept study shows us that we can engineer pathways in our hybrids to photosynthetically produce limonene, which belongs to a class of molecules called terpenoids, which are also precursors to many high-value compounds such as fuels, anticancer and antimalarial drugs.”

Mehta said that their goals for this line of research are to determine if their method can produce more complex compounds, like fuels and pharmaceuticals, and if so, work on scaling up the process to be marketable.

“I think it would be incredible to get to the point where we could assure that every bit of carbon in a high-value compound comes from CO2,” Mehta said. “This could be one way to recycle CO2 waste in the future.”

The team also said that in their quest to understand and perfect endosymbiotic systems to advance biotechnology, they will also answer many fundamental evolutionary questions along the way. “This will happen whether we intend it or not,” Mehta said. “We are always keeping an eye on how our work can answer some of the mysteries behind how life evolved. In my view, the best way to engineer endosymbiotic systems will be by recreating the evolution process in the lab. Finding answers to some of biology’s biggest questions will come naturally.”

Illinois researchers Yang-le Gao, Jason Cournoyer, Bidhan De, Catherine Wallace, Alexander Ulanov and Michael La Frano also participated in this study. The National Institutes of Health supported this research.

Discussion about this post