Senate Democrats on Sunday passed a sweeping healthcare, tax and climate change bill that will allow Medicare to negotiate prescription drug costs — a significant political win as the party tries to send a message before the midterm election that it is delivering on its promises.

The drug-price plan is the centerpiece of the Democrats’ bill, the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. The measure would also establish incentives to combat the climate crisis, impose new taxes on corporations and provide $4 billion for the Bureau of Reclamation to combat drought in the West — a last-minute addition.

The bill, approved via a fast-track legislative procedure that didn’t allow for a Republican filibuster, passed on a 50-50 vote, with Vice President Kamala Harris breaking the tie.

No Republicans supported the bill. It will now go before the House, where a vote is expected Friday.

Before passage, senators slogged through dozens of unsuccessful votes on amendments put forward mainly by Republicans to try to stop the bill or at least make it politically difficult for Democrats.

Republicans succeeded in killing one provision that violated Senate budget rules. It would have capped the price of insulin at $35 a month in the private insurance market.

President Biden and congressional Democrats sorely need the legislative victory as they head toward the midterm elections, which traditionally favor the party out of power.

The package comes at the end of a remarkably productive sprint for the closely divided Senate. In recent weeks, the chamber has enacted a bipartisan gun bill, a boost for semiconductor manufacturing and aid for veterans exposed to toxic burn pits.

The enactment of the Medicare drug negotiation policy — which Democrats have been pushing for nearly two decades — would mark a significant accomplishment that is likely to be popular with voters who are eager to go after drugmakers.

It amounts to the most substantial change in healthcare policy since the Affordable Care Act was passed in 2010. But it will initially have a limited impact on the pocketbooks of the nearly 64 million seniors in Medicare.

Negotiations between Medicare and drugmakers wouldn’t start until 2026, and would at first be limited to 10 drugs, adding more over time.

Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), a longtime proponent of Medicare price negotiations, called that portion of the bill “pretty weak.”

But Democrats rejected his amendment Sunday to strengthen the Medicare provisions.

Under the plan, Medicare will be able to negotiate over some of the most expensive drugs on the market, saving the federal government an estimated $288 billion over a decade, according to the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office.

Likely targets for negotiations include Eliquis, an atrial fibrillation medication used by well over 2 million Medicare beneficiaries; the diabetes drug Januvia, the prostate cancer drug Xtandi; and the rheumatoid arthritis drug Orencia, according to industry players who are tracking the legislation. That list could change if pricier drugs enter the market in the next four years.

Chris Condeluci, founder of CC Law & Policy and a former staff member for Senate Finance Committee Republicans, predicted negotiations would not have a significant impact on the vast majority of Medicare beneficiaries, because most don’t use the most expensive drugs and are therefore unlikely to see direct savings.

“Unless your premiums go down, it doesn’t matter if Medicare is spending less” overall, he said.

But the bill would also cap Medicare beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket drug expenses at $2,000 per year, a policy that could help the approximately 1.4 million enrollees who hit that amount each year, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Drugmakers generally like the out-of-pocket cap because the federal government will pick up the tab after patients spend the maximum.

The measure would also impose a cap on drugmakers’ price increases, though Democrats had to scale back the inflationary cap on Saturday when the nonpartisan Senate parliamentarian ruled that it didn’t adhere to Senate rules.

The inflationary cap isn’t a huge hit for the pharmaceutical industry because “companies have been self-policing,” said Ipsita Smolinski, a health policy advisor and managing director of Capitol Street, a research and consulting firm.

“They know they’d be on the front page of the Wall Street Journal or the New York Times if they obnoxiously price hike their products,” she said.

But drug manufacturers have strongly fought negotiating their prices with Medicare. Drugmakers and Republicans warn that allowing negotiations would stifle innovation of new drugs that pharmaceutical companies suspect would be affected. They also say the prospect of negotiations could prompt drugmakers to charge more when drugs first come on the market.

Medicare was barred from negotiating drug prices in 2003, with the establishment of the Medicare Part D drug program. The ban essentially allows pharmaceutical companies to set their own costs for Medicare, even though other government programs, such as Veterans Affairs, may negotiate for lower prices.

Drugmakers once had one of the most powerful lobbying groups in Washington, and still lead the pack in terms of spending to influence lawmakers. But their political power has waned in recent years amid high-profile price hikes, such as former Turing Pharmaceuticals Chief Executive Martin Shkreli’s decision to raise the price of one older drug by 5,000%.

The legislation is a fraction of what Democrats had originally hoped to enact — a $3.5-trillion proposal that would have rewritten much of the nation’s social safety net, including home healthcare, child care and universal pre-K programs. That effort ended when Sen. Joe Manchin III (D-W.Va.) said in December he would not go along with such an ambitious plan.

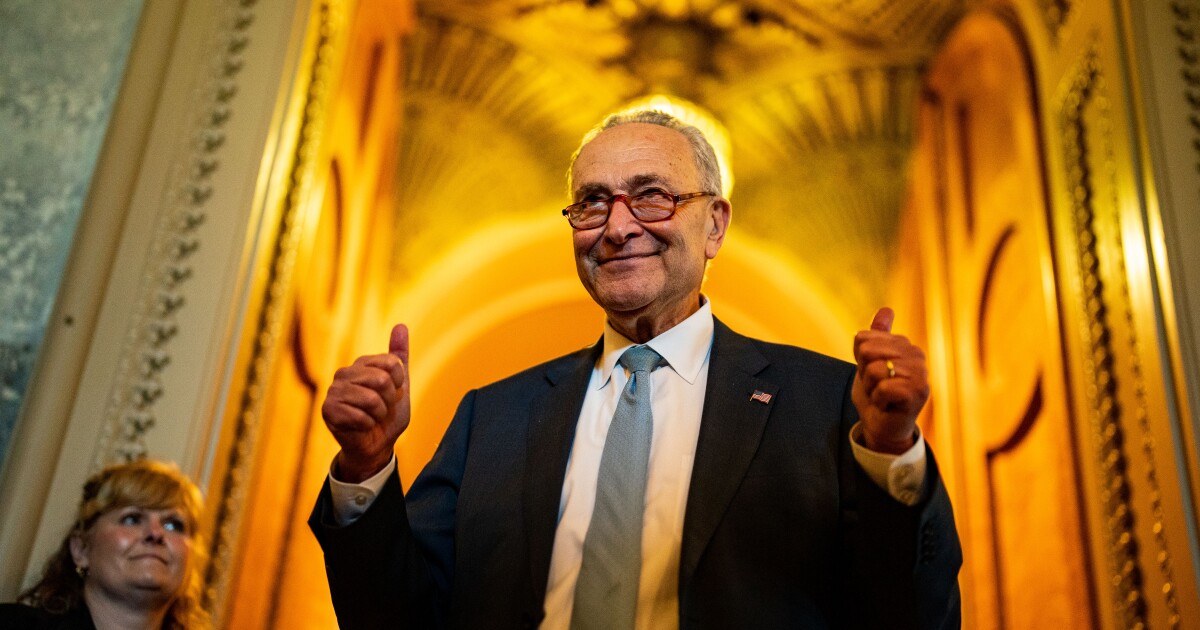

But after secret negotiations between Manchin and Senate Majority Leader Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.), they resurrected portions of the bill last month.

The bill also seeks to address climate change. In an attempt to reduce emissions, it offers incentives for consumers to buy energy-efficient appliances and cars, and for manufacturers to make such products. According to Democrats, the climate policies would reduce emissions by roughly 40% by 2030.

About $9 billion would go to consumer home energy rebate programs. Lower- and middle-income people would be eligible for a $4,000 tax credit for buying a used clean car and up to $7,500 for buying a new one. Billions more would be spent to accelerate U.S. manufacturing of solar panels, electric vehicles and other clean products.

Finally, the bill would impose new taxes on wealthy corporations and their stock buyback programs — and would send new funding to the Internal Revenue Service, which the agency says it will use to crack down on wealthy tax cheats.

Discussion about this post