South Africa’s police service is in no way separated from the society it serves. Issues such as sexism, racism and classism that permeate society are reflected in law enforcement. For many South Africans, a functional police service, free from discrimination, is something they have never known.

For both society and law enforcement, there is a long history of inequality to unlearn, according to Ziyanda Stuurman, the author of Can We Be Safe? The Future of Policing in South Africa.

“As much as we would have liked to see a police service that changed and was what it said it was in terms of [being] human rights-based and community oriented, that’s really difficult to do when you have… [a] more than 100-year history that they have to contend with,” said Stuurman.

“You don’t unlearn that immediately. And just like we as a society didn’t unlearn the racism, the violence, the brutality of our history, our police service is also struggling to do that.”

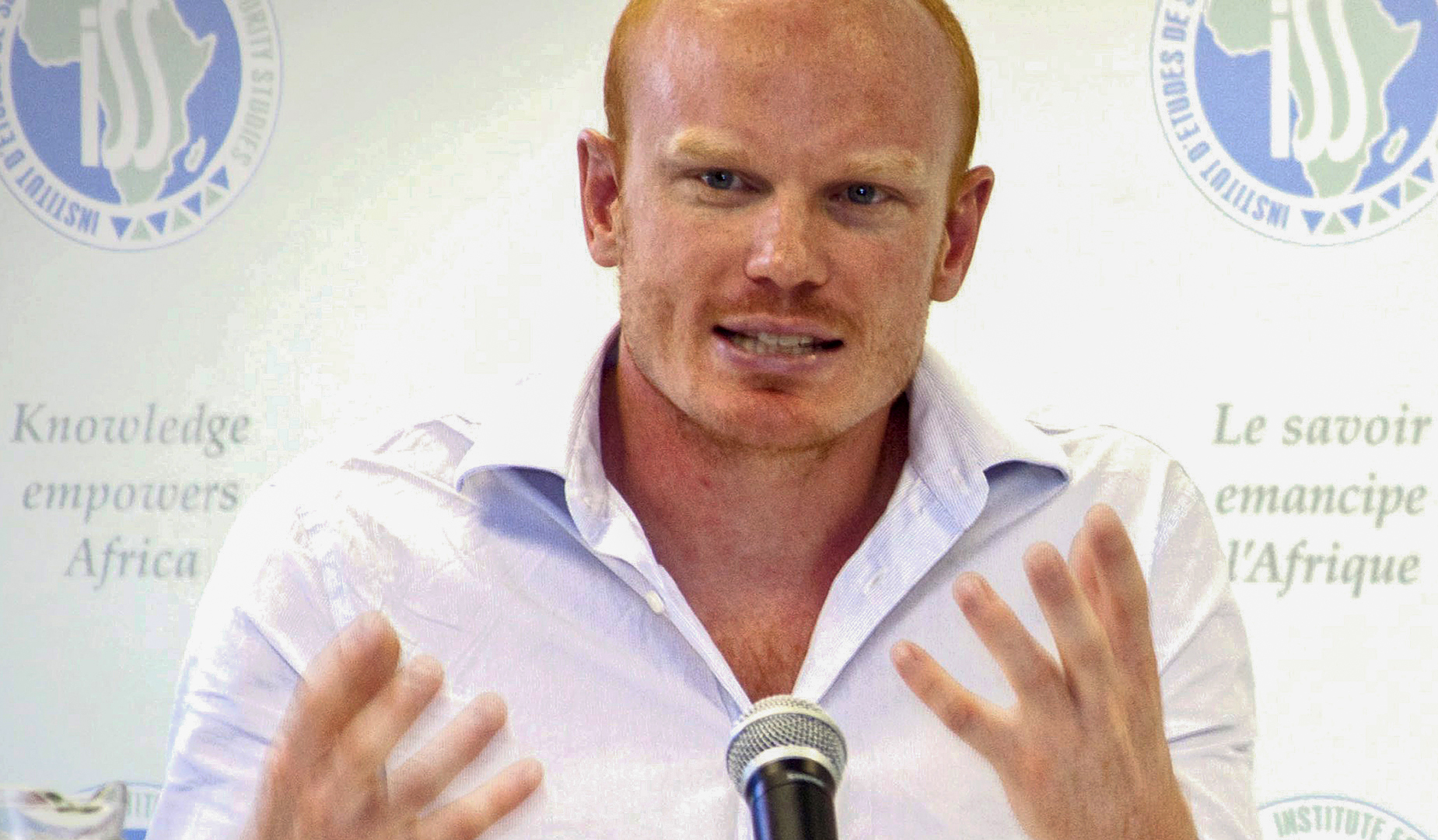

Stuurman was speaking at a webinar hosted by the Hanns Seidel Foundation and the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) on Tuesday titled “Police reform is about officers, not just institutions”. Dr Andrew Faull, senior researcher for justice and violence prevention at the ISS, chaired the discussion, while Rofhiwa Maneta, freelance journalist and author of A Man, a Fire, a Corpse, joined Stuurman as a speaker.

Without a change to the “muscle and bone” of the police service, it is difficult to establish the sort of work police officers are meant to do, continued Stuurman.

“This is not just the police service’s fault. I think often, we really lay a lot of things at the feet of police that are really… massive, grand societal issues that we can’t just expect police to solve. You know, we can’t police away inequality, poverty and unemployment,” she said.

There needs to be a concerted effort on the part of society to change the patterns around racism and violence, rather than an expectation that the police will serve as a buffer between people and these patterns, according to Stuurman.

Police as individuals

Maneta referred to a conversation he had with his father — a black police officer who began his service in 1986 — during the interview process for the book, A Man, a Fire, a Corpse. The book is about his father’s 30-plus years of working in the police service.

“I essentially asked my dad, why is it that the majority of people he would… arrest were people who looked like me. And he kind of turned the question back and he was like, ‘Ah, well, don’t blame this on me. You know, people are… the sum of their patterns’,” said Maneta.

Maneta’s father viewed the middle class as being those who had access to a certain number of second chances. Whereas someone living in a poor community such as Alexandra in Johannesburg is often one mistake away from being sent to jail, someone living an affluent lifestyle in nearby Sandton has a “safety net of privilege” should they make a mistake, said Maneta.

As a policeman, Maneta’s father was guided by the principle of investigating-to-arrest, rather than arresting-to-investigate. While working on high-profile murders and cold cases, he was often under pressure from his bosses to make an arrest simply to show that some progress was being made.

“He was always strongly opposed to that,” said Maneta.

A further guiding principle for Maneta’s father was that there is a distinction between truth and fact. A witness to a crime may claim they saw a navy blue car at a crime scene, when in fact it was a black car. The witness would be telling the truth, but would be factually incorrect, said Maneta.

Despite the honest approach his father took to policing, Maneta has a deep distrust of police officials. He shared that, as a young, black man, his personal interactions with police officers have been “less than pleasant”.

“I went to a suburban school, but I was from Soweto. So, whenever my friends and I would get off the bus and walk the rest of the way to school, it wasn’t uncommon to have police stop us… ask us where we were going, when we were in full school uniform,” said Maneta.

While his father has told him that the police institution is essentially made up of individuals, Maneta argues that he never experiences police as individuals. They always have some sort of “institutional backing”.

“The fact that they have a gun and the fact that the state… outsourced a particular kind of violence to them means they can act however they want to,” he said.

Distrust in police

The lack of trust in police is partly rooted in the invasive techniques they employ within certain communities, such as the coloured communities of the Western Cape that have high levels of gang violence, according to Stuurman. These communities often face a strategy of “blitz attacks” involving roadblocks, banging on doors and invasive questioning.

“I think that that has… such a powerfully negative effect on people’s lives,” said Stuurman.

She cited the case of gang members who leave gangs to reintegrate into society — a difficult decision to make — only to continually be considered suspects in crimes due to them still having gang tattoos on their bodies.

“It’s so hard to build trust in an environment like that, where again, this sort of perspective on policing doesn’t see people for who they are… it sees them for how they’ve been described as a threat, as a problem, as a former gang member,” said Stuurman.

While there should be a police service in South Africa attempting to create law and order, it should not be the main interface between poor communities and the government, she continued. Rather, government should roll out plans to create safer communities alongside police services.

“This is very counterintuitive, I think, to the way that the [South African Police Service] works, where they feel like ‘We’re doing this or we’re not’, and they’re never looking at what other departments are doing,” said Stuurman.

Communities and police can work together to create thriving environments, she added, using the example of police supporting informal traders in setting up specific days to sell their wares within their own communities.

“That’s really difficult to do when you have people who are exchanging money and who are trying to set up a market economy in a dangerous setting, and where police don’t see the opportunity for them to help communities co-create this space.”

Certain problems that are currently addressed by police could be targeted through other services, thereby reducing the need for policemen on the ground, said Stuurman.

“I think we’re just at a point where we fall back on saying, ‘It’s the police or nothing’, where there’s so much in between, and there’s really a potential… where you’re providing services,” she said.

“If you don’t have this enormous need for police officers to be on the street all the time, their role in society becomes [very] different to what their role is right now.” DM/MC

Related Articles

![]()

.png)

Discussion about this post