The Oxford English dictionary defines history as “the study of past events, especially as a subject at school or university.” At the end of a war or during the clash of civilisations, history is typically written by the winner, or at the very least by those in positions of relative strength, of privilege, because the ones being oppressed are too busy fighting for their freedoms and rights to have the luxury of recounting the past.

This is why you have not read or heard enough about legends such as Suleiman ‘Dik’ Abed. In India, the history that is taught in schools can be hard to relate to, because the events described usually happened hundreds, or even thousands of years ago. In South Africa, a lot of the history, a lot of the churn, is much more recent. And still happening.

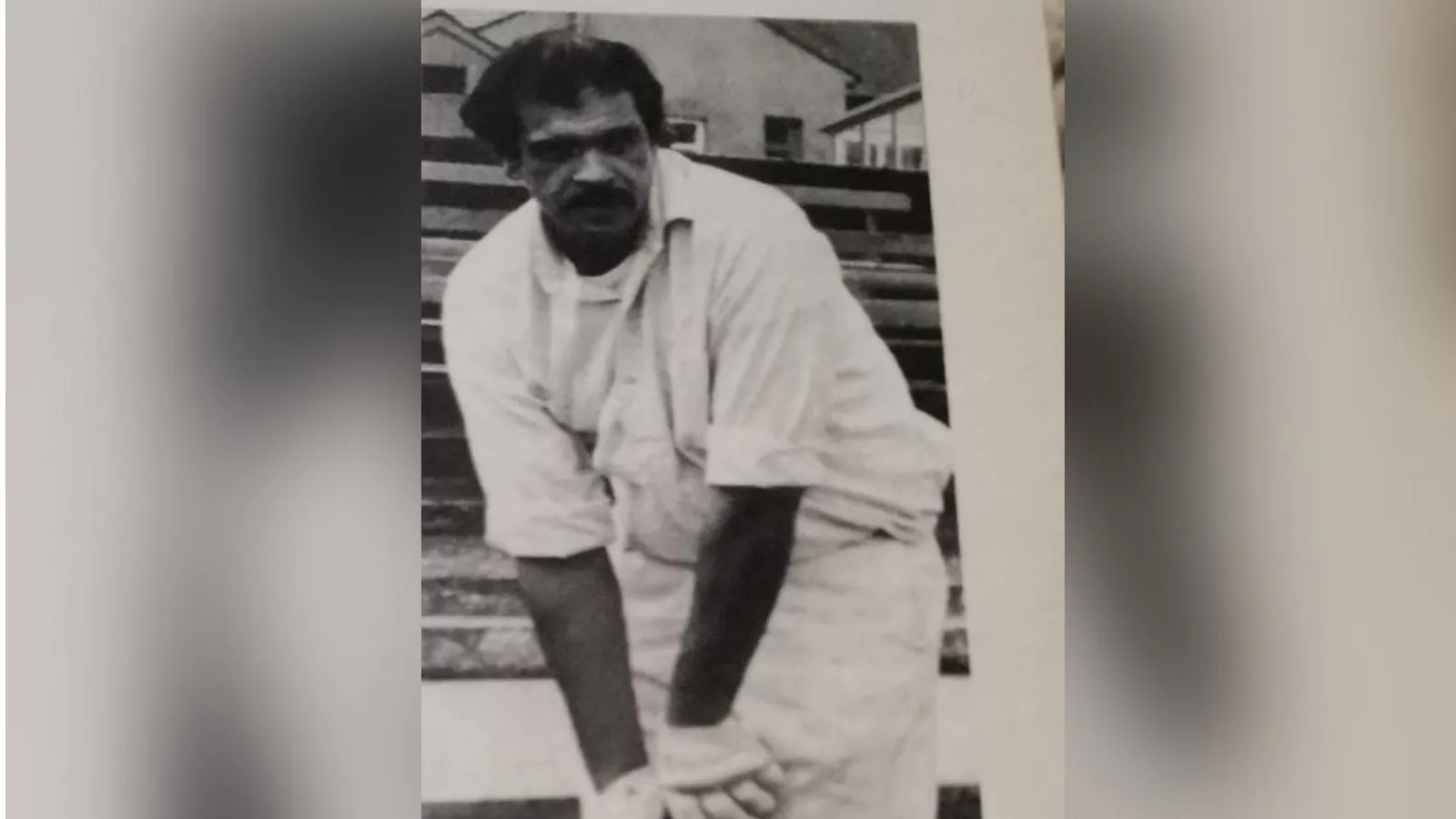

Dik Abed, for example, was alive till as recently as 2018, when he died in the Netherlands, at the age of 73. But, we are here not to talk of his death, rather of his life. Dik was the youngest of five brothers, all of whom were excellent sportsmen. Gasant ‘Tiny’ Abed, the eldest, and who got his ironic nickname because he had an imposing build was part of the SA Cricket Board of Control (Sacboc) national team that toured Kenya in 1958.

The second Abed, Salie ‘Lobo’ Abed, was also on that 1958 tour. Dik was far too young at 15 then. The story goes that Lobo was playing for the Western Province Indian team in the national racially-based tournament in Durban in 1948. Shaikh Moosa Goder, the wicketkeeper, was injured and Lobo was drafted in as a replacement behind the stumps.

The rest is history. Or it should have been. Basil D’Oliveira is on record saying Lobo is the best wicketkeeper he had ever seen, forget about the best South African stumper. Another brother, Goolam went to England to pursue a rugby career with Bradford Northern. But, back to Dik, who learnt his early cricket on the streets outside his home, Muir Street, where as many as 30 youngsters would gather each Sunday morning for a game.

Muir Street, in the heart of District Six, was one of the flashpoints of the implementation of the Group Areas Act, in which more than 60,000 people were forcibly removed from homes that had been theirs for generations, in the 1970s, by the apartheid regime.

“Once you had been dismissed, you had to wait until everyone else had had a chance to bat before you could bat again,” Dik recalled to Mogamad Allie who wrote the book ‘More than a Game’ that chronicled the history of the Western Province Cricket Board from 1959 to 1991.

“Batsmen struggled to cope with bowlers intent on hitting them in places where it hurt most,” said Dik. “But these confrontations were invaluable: it toughened us up and helped us develop skills that we may not otherwise have developed.”

While Dik enjoyed hitting the ball a long way, he admitted that running was not his cup of tea, which is why he initially never took to bowling. But when he did, he delivered fast leg cutters with an unconventional grip, and this posed a serious problem to batsmen. Very quickly, Dik was too good for local cricket or the Dadabhay inter-provincial tournament.

It was then that Damoo Bandsa, a cricket tragic in the region, wrote letters to clubs in England telling them of Dik’s exploits. Enfield, in the Lancashire League, showed interest and offered 600 pounds for a season, but they would not front up for Dik’s ticket to the United Kingdom. Nevertheless, the offer was taken up, and this time, the rest really is history. Even if it’s not a significant part of South Africa’s history.

In his second season, Dik took 120 wickets at 8.76 and led Enfield to their first league title in 25 years. When Dik retired from league cricket in 1976, he had taken 855 wickets at 10.27 and scored 5271 runs at an average of 27.77. Those numbers are staggering. And if you think they are an aberration, or perhaps that of someone who played a grade of cricket well lower than he could have, consider this: Dik was eventually voted as one of the all-time greats of Enfield, ahead of Sir Clyde Walcott, Conrad Hunte, and Madan Lal, who all played for the club with distinction.

Naturally, when he was ruling the roost in the Lancashire League, Dik received several trials from County sides. But, it was only later that he came to know that none of these was genuine, as there had been an unofficial diktat from the highest cricketing powers in the land, not to take him in, as this could lead to another D’ Oliveira situation.

But, it did not end here. In 1970, Dik received an invitation to be a part of a Springbok team touring Australia, along with Owen Williams, a left-arm spinner rated highly, another Saboc legend. “I refused to go as a glorified baggage master,” Williams said. This was a reference, but it was clear that the two coloured players were only being taken along because the tour was under threat of being called off in reaction to South Africa’s apartheid policies.

Dik declined the invitation, as did Williams, and the tour never happened. Just when you think it was all over, Dik was back in the thick of things when he asked for press accreditation at Newlands for the Test against the visiting Australians in 1970. The press box at the ground was out of bounds for coloured people, so he was given a small table and a seat in the Railway Stand, where “non-European people” were allowed to watch the game from.

Today, if you go to Bo Kaap, just minutes from Muir Street where Dik grew up, there are signs of gentrification everywhere. The cobbled stone roads are lined with colourful houses, the kind you might find in some quaint town in Europe. Homes that were traditionally owned by Cape Malays, in the streets surrounding the Ouwal Mosque, constructed in 1794, recognised as the first in South Africa, are now selling for millions of rand.

There are people of all hues moving into what is becoming a chic neighbourhood, with Signal Hill right there and dramatic views of the waterfront at one end, the city in the middle and magnificent Table Mountain at the other. Today, there are kids who live in Bo Kaap, who play cricket on the manicured fields of the privately funded Diocesan College, commonly known as Bishops, in the leafy suburb of Rondebosch and have a pathway to playing for the Proteas, something Dik could not even dream of.

But, the sadness in all this, is that there isn’t one statue of Suleiman Dik Abed, anywhere to be seen. And this is because history, often, is not what is written, but what is left out.

Get all the IPL news and Cricket Score here

Discussion about this post