The government has eliminated Marsden grants for humanities and social sciences. Shanti Mathias explains what Marsden grants are, and why the change has worried so many researchers.

OK, so what’s the Marsden Fund?

The Marsden Fund was established in the 1990s to provide contestable government funding for research in New Zealand. The funding comes from the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, and is administered by the Royal Society Te Apārangi. In 2024, the total pool was $77.7 million, divided into 113 grants for different projects. Researchers apply for the funding, and a council appointed by the science minister goes through the proposals. Ten different panels of experts in different areas (i.e. social sciences, humanities, physics and chemistry, biomedical science) go through the proposals and decide which ones they want to pick. While there are a few different types of grants, all Marsden-funded projects are distributed over three years, and pay for salaries, research materials, institutional costs and students and postdoctoral positions associated with the project, giving researchers time to thoroughly investigate an issue.

What sort of research are we talking about?

Marsden Fund grants are for “blue skies” research, which means research without a single clear outcome or economic benefit; the expectation is that an increased amount of possibilities and knowledge can have impacts that researchers can’t always directly see. Any research into the fields of science, engineering, mathematics, the social sciences and the humanities has been eligible – until now.

Oh?

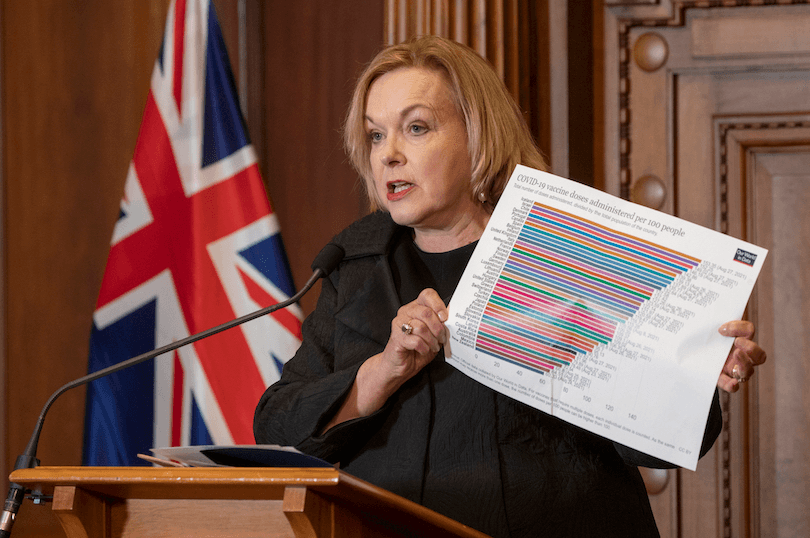

Yesterday, Judith Collins, the minister of science, innovation and technology, announced major changes to the Marsden Fund that will apply from 2025. These changes mean that at least 50% of the money has to go to projects that have economic benefits to New Zealand. The panels that made decisions for humanities and social sciences are being disbanded, as funding will no longer be directed to these areas. “Real impact on our economy will come from areas such as physics, chemistry, maths, engineering and biomedical sciences. The Marsden Fund will continue to support excellent researchers in New Zealand, who are looking to create a better country for us all,” Collins said in a press release.

Why isn’t the government funding the humanities any more?

Collins’ explanation is economic: “The government has been clear in its mandate to rebuild our economy. We are focused on a system that supports growth, and a science sector that drives high-tech, high-productivity, high-value businesses and jobs,” she said in the same press release.

How has this change been received?

In the research community, not well. It’s been described as “very concerning” (Universities New Zealand), a “significant step backwards” (University of Otago), and “chilling” (Troy Baisden, co-president of the NZ Association of Scientists).

What about outside the academic world?

The Act Party welcomed the move, saying in a press release that in the past funding had been “prioritised for spirituality, activism and identity politics over high-quality public good research that benefits all New Zealanders”.

Business lobby group BusinessNZ was also supportive, putting out a press release that said “Directing the Marsden Fund to focus more narrowly on research that will help to support high-tech, high-productivity, high-value businesses and jobs is the right move.”

And is it proven that humanities and social science research doesn’t contribute to the economy?

It’s long been true in scientific research that it’s often easier to get funding for “hard science” like physics, engineering and biomedical health than humanities research, like history, languages and sociology. A scroll through some of the 2024 grants shows the range of humanities topics; a project to understand “the historical drivers and possible futures of global cultural and linguistic diversity”, research “examining which syllables are stressed in te reo Māori and why”, research into a Te Tiriti-affirming tax system design, and studying how people think about waste in a circular economy. It’s impossible to compare whether this research is of more or less value than studying the gut biomes of alpine insects, “how plants hear the contrasting vibrations of a bee buzzing and a caterpillar chewing”, looking at the environmental risks of forever chemicals or tracking cosmic-ray particles.

Many scientists and research professionals say that different disciplines learn from each other, and that a healthy research system has many parts. “The work that our colleagues in the humanities and social sciences do is incredibly important. We can do all the work in developing clean technologies we want, but if we don’t understand the barriers to people purchasing that tech? It becomes useless,” said Nicola Gaston, co-director of the MacDiarmid Institute for Advanced Materials and Nanotechnology, who described herself as “absolutely disgusted” by how physical science was being “weaponised” against the humanities.

“Forcing economic benefits into the Marsden fund doesn’t get us a two-for-one. Instead, it is likely to erode the excellence, quality and efficiency of both,” said Troy Baisden, co-president of the New Zealand Association of Scientists, in a comment to the Science Media Centre.

“It is naïve to think that we can tackle the current and future challenges we face as a country and a world without our humanities and social science scholars and their research,” said Siouxsie Wiles, a microbiologist and associate professor at the University of Auckland.

“Humanities and social sciences are the disciplines that underpin our society and research in these areas is crucial for understanding society transformation,” said Universities New Zealand in a press release. “In a time of societal upheaval, not only in Aotearoa New Zealand but worldwide, government disinvestment in these disciplines is astonishing.”

Describing the process of applications in a piece for The Spinoff, former Marsden Council chair Juliet Gerrard said: “Each year, it was impossible to know which of the chosen ideas would fly the highest, but the process, inevitably imperfect, produced a suite of research that did us proud… No one knows which ideas will be needed to face future challenges and seize opportunities. But a community of researchers across all disciplines pursuing their best ideas is our best insurance for making sure we have access to those ideas when we need them.”

In a joint letter, a number of professional associations representing fields in the humanities and social sciences called on Collins to “reverse the devastating decision to stop supporting our research”. Suggesting only “areas such as physics, chemistry, maths, engineering and biomedical sciences” made a “real impact” on the economy was “a dangerously narrow and impoverished view”, said the letter. “As many scientists have pointed out, scientific research and innovation depend on critical interventions from humanities and social science scholars.”

Have there been changes to any other research funding?

The Catalyst Fund, a government investment in research and innovation that creates international relationships and impacts New Zealand’s economy, environment and society has been updated too, to “deliver greater economic impact for New Zealand,” Collins said. The new plan “focuses our funding on clear growth areas of quantum technology, health, biotechnology, artificial intelligence, space and Antarctic research,” Collins said in a press release yesterday. Catalyst Funds distribute $20m-$30m each year.

“International collaboration is most effective around fundamental research in areas of mutual excellence and interest. Attempting to extract economic outcomes undermines the quality of collaborations as well as their long-term benefits,” said Baiden, of the Catalyst fund changes.

Discussion about this post