Changes to the law and subsidies for solar, are steps in the right direction (CFOTO/Future Publishing via Getty Images)

Over the course of this year, Eskom’s energy availability factor — the gauge of its available generation capacity unaffected by breakdowns — has continued to reach record week-on-week lows.

In the first week of 2023, less than half of the utility’s generation capacity was available — almost 10% lower than at the start of 2022. In week 10 of this year, the figure was about 4% lower than in the same week of last year and 7% lower than in 2021.

The question on every South African’s mind, especially in the wake of former Eskom chief executive André de Ruyter’s explosive interview with e.tv’s Annika Larsen — in which he spoke frankly about the endemic corruption and mismanagement at the utility — is simple, but desperate, “When will it end?”

De Ruyter’s answer to that question was not an optimistic one. He said to expect at least stage six blackouts (and possibly worse) during winter.

Several experts and commentators have echoed De Ruyter’s bleak view. In interviews with Biznews, former Eskom executive Robbie van Heerden said load-shedding would go to stage eight this winter and not abate for many years thereafter. Research and consulting firm Intellidex’s capital markets head Peter Attard Montalto said that, according to his analysis, we should expect consistent stage seven load-shedding from July.

After his e.tv interview, De Ruyter seems to have gone missing. No one — including the ANC’s lawyers who are trying to serve papers on him in an attempt to sue him for defamation over claims he made in the interview — has been able to find him in weeks.

I hope De Ruyter is safe. It is a lamentable sign of South Africa’s decline that someone of his calibre, who tried his best to fix some of the mess, can’t speak out about corruption without legitimately fearing Soviet-style assassination.

I also hope De Ruyter (and the others) are mistaken. Is this a false hope? After February’s budget speech, for the first time, I don’t think it is.

The national government has — albeit 10 years too late — finally woken up to a simple fact. For decades, South Africa has put all its energy eggs in the Eskom basket. But since returns on this investment continue to diminish, maybe we need some more eggs.

Early attempts at egg diversification have shown encouraging results. In August 2021, the licensing threshold for generation by those other than Eskom was raised to 100MW. This allowed new solutions to the energy crisis to spring up.

Notably, the City of Cape Town announced plans last year to procure hundreds of megawatts from independent power producers, lessening the municipality’s reliance on Eskom.

Unfortunately, due to national government red tape, most of Cape Town’s plans were never going to materialise as quickly as needed. The city only planned to be able to mitigate three stages of load-shedding by 2027. After load-shedding rose to stage six in June 2022 — a serious threat to municipal infrastructure — Mayor Geordin Hill-Lewis drafted a “10-point plan” for the national government to end the crisis.

One of the mayor’s suggestions was to exempt municipalities from “unnecessary legislation and regulations (including those governing municipal procurement) that will delay bringing new generation capacity online”.

“This problem is solvable if we all work together,” Hill-Lewis wrote. “But it requires clear and decisive leadership, and a willingness to do things differently.”

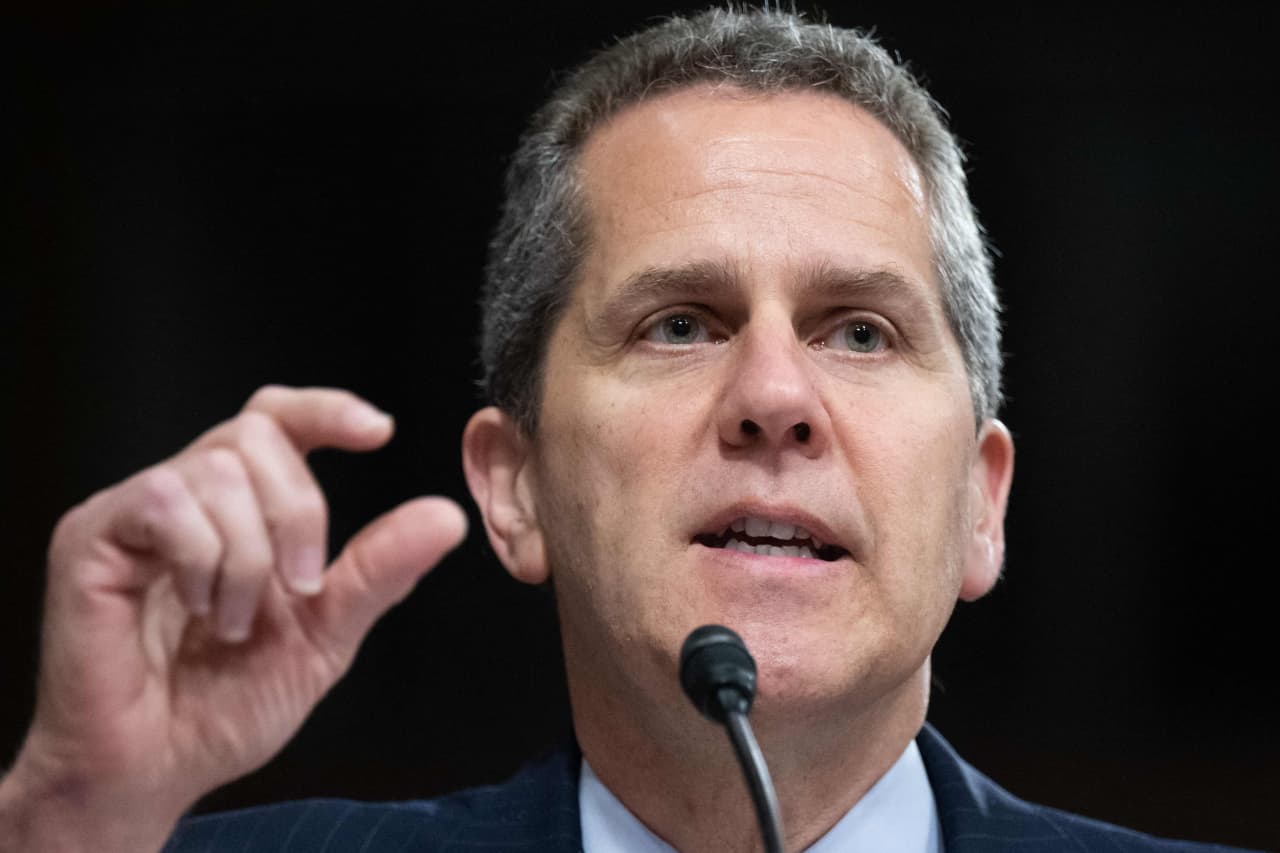

Clear and decisive leadership finally seems finally to have been shown by finance minister Enoch Godongwana, who seems to recognise that there are millions of eggs that can be put in the energy basket. And they’re easy to find; they’re above most of our heads.

First, great news for Capetonians. Godongwana has granted the city — in line with the mayor’s request — an exemption from provisions of the Preferential Procurement Policy Framework Act that require a competitive tender process for all contracts of a certain value. This means the city can — and will — start buying electricity from anyone willing to sell it, including residents and businesses with solar installations.

The fact that electricity can now be sold on to municipalities makes investing in solar much more financially viable. The private sector has already come up with a range of innovative financing models to make it even more accessible (including rental of units represented by tokens on a blockchain, my current project).

However, the single factor deterring most middle-class South Africans from investing in solar panels on their roofs has been the cost. Going “off grid” costs most households between R150 000 and R300 000. Godongwana’s announcement of a 25% rebate for installation costs up to R15 000 lowers this, though the relatively small cap possibly means it won’t lower the cost enough to make solar affordable for most households.

The second bit of good news, though, is that the treasury is finally recognising that the economic benefits of households generating electricity justify a cost to the fiscus. If successful in aiding the country’s security of supply, rebates could continue and even increase over time.

On the other hand, the 125% rebate on offer to businesses — without a threshold — is a significant immediate step. It will (directly) offer improved energy security to those driving the economy as well as (indirectly) making every South African more energy secure, especially those living in municipalities (such as Cape Town) that plan to buy energy from residents producing an excess.

These are all steps in the right direction and we can all only hope they will gather momentum. The good news is, we don’t have to walk very far. Just a few steps up a ladder lands us right on the answer to South Africa’s energy crisis.

Ahren Posthumus is the spokesperson of the SunCash Initiative

Discussion about this post