The lab-leak theory lives! Or better put: It never dies. In response to new but unspecified intelligence, the U.S. Department of Energy has changed its assessment of COVID-19’s origins: The agency, which had previously been undecided on the matter, now rates a laboratory mishap ahead of a natural spillover event as the suspected starting point. That conclusion, first reported over the weekend by The Wall Street Journal, matches up with findings from the FBI, and also a Senate Minority report out last fall that called the pandemic, “more likely than not, the result of a research-related incident.”

Then again, the new assessment does not match up with findings from elsewhere in the federal government. In mid-2021, when President Biden asked the U.S. intelligence community for a 90-day review of the pandemic’s origins, the response came back divided: Four agencies, plus the National Intelligence Council, guessed that COVID started (as nearly all pandemics do) with a natural exposure to an infected animal; three agencies couldn’t decide on an answer; and one blamed a laboratory accident. DOE’s revision, revealed this week, means that a single undecided vote has flipped into the lab-leak camp. If you’re keeping count—and, really, what else can one do?—the matter still appears to be decided in favor of a zoonotic origin, by an updated score of 5 to 2. The lab-leak theory remains the outlier position.

Are we done? No, we aren’t done. None of these assessments carries much conviction: Only one, from the FBI, was made with “moderate” confidence; the rest are rated “low,” as in, hmm we’re not so sure. This lack of confidence—as compared with the overbearing certainty of the scientists and journalists who rejected the possibility of a lab leak in 2020—will now be fodder for what could be months of Congressional hearings, as House Republicans pursue evidence of a possible “cover-up.” But for all the Sturm und Drang that’s sure to come, the fundamental state of knowledge on COVID’s origins remains more or less unchanged from where it was a year ago. The story of a market origin matches up with recent history and an array of well-established facts. But the lab-leak theory also fits in certain ways, and—at least for now—it cannot be ruled out. Putting all of this another way: ¯\_(ツ)_/¯.

That’s not to say that it’s a toss-up. All of the agencies agree, for instance, that SARS-CoV-2 was not devised on purpose, as a weapon. And several bits of evidence have come to light since Biden ordered his review—most notably, a careful plot of early cases from Wuhan, China, that stamps the city’s Huanan market complex as the outbreak’s epicenter. Many scientists with relevant knowledge believe that COVID started in that market—but their certainty can waver. In that sense, the consensus on COVID’s origins feels somewhat different from the one on humans’ role in global warming, though the two have been pointedly compared. Climate experts almost all agree, and they also feel quite sure of their position.

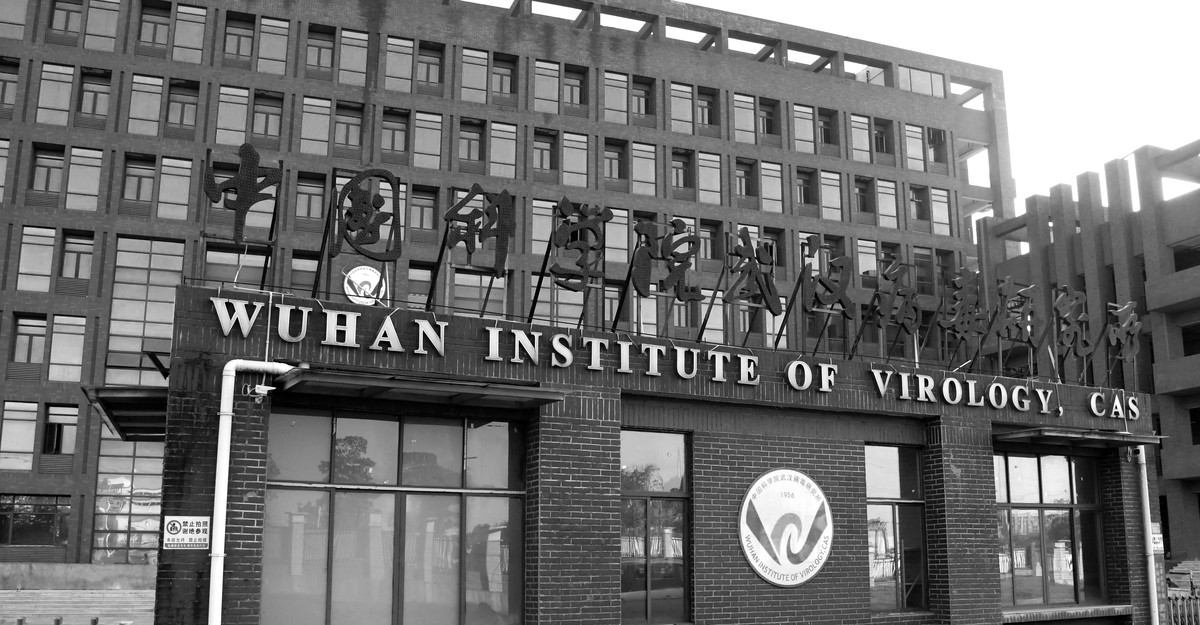

The central ambiguity, such as it is, of COVID’s origin remains intact and perched atop a pair of improbable-seeming coincidences: One concerns the Huanan market, and the other has to do with the Wuhan Institute of Virology, where Chinese researchers have specialized in the study of bat coronaviruses. If COVID really started in the lab, one position holds, then it would have to be a pretty amazing coincidence that so many of the earliest infections happened to emerge in and around a venue for the sale of live, wild animals … which happens to be the exact sort of place where the first SARS-coronavirus pandemic may have started 20 years ago. But also: If COVID really started in a live-animal market, then it would have to be a similarly amazing coincidence that the market in question happened to be across the river from the laboratory of the world’s leading bat-coronavirus researcher … who happened to be running experiments that could, in theory, make coronaviruses more dangerous.

One might argue over which of these coincidences is really more surprising; indeed, that’s been the major substance of this debate since 2020, and the source of endless rancor. In theory, further studies and investigations would help resolve some of this uncertainty—but these may never end up happening. A formal inquiry into the pandemic’s origin, set up by the World Health Organization, had intended to revisit its claim from early 2021 that a laboratory source was “extremely unlikely.” Now that project has been shelved in the face of Chinese opposition, and the Wuhan Institute of Virology has long since stopped responding to requests for information from its U.S.-based research partners and the NIH, according to an inspector general’s report from the Department of Health and Human Services.

In the meantime, the smattering of facts that have been introduced into the lab-leak debates over the past two years, have been, at times, maddeningly opaque—like the unnamed, “new intelligence” that swayed the Department of Energy. (For the record, The New York Times reports that each of the agencies investigating the pandemic’s origin had access to this same intelligence; only DOE changed its assessment to favor the lab-leak explanation as a result.) We’re only told that certain fresh and classified information has changed the minds of some (but only some) unnamed analysts who now believe (with limited assurance) that a laboratory origin is most likely. Well, great, I guess that settles it.

When more specific information does crop up, it tends to vary in the telling over time; or else it’s promptly pulverized by its partisan opponents. The Journal’s reporting, for instance, mentions a finding by U.S. intelligence that three researchers at the Wuhan Institute of Virology became ill in November 2019, in what could have been the initial cluster of infection. But how much is really known about those sickened scientists? The specifics vary with the source. In one telling, a researcher’s wife was sickened, too, and died from the infection. Another adds the seemingly important fact that the researchers were “connected with gain-of-function research on coronaviruses.” But the unnamed current and former U.S. officials who pass along this sort of information can’t even seem to settle on its credibility.

Or consider the reporting, published last October by ProPublica and Vanity Fair, on a flurry of Chinese Community Party communications from the fall of 2019. These were interpreted by Senate researcher Toy Reid to mean that the Wuhan Institute of Virology had undergone a major biosafety crisis that November—just when the COVID outbreak would have been emerging. Critics ridiculed the story, calling it a “train wreck” premised on a bad translation. In response ProPublica asked three more translators to verify Reid’s reading, and claimed they “all agreed that his version was a plausible way to represent the passage,” and that the wording was ambiguous.

Maybe this is just what happens when you’re trapped inside an information vacuum: Any scrap of data that happens to float by will push you off in new directions.

Discussion about this post