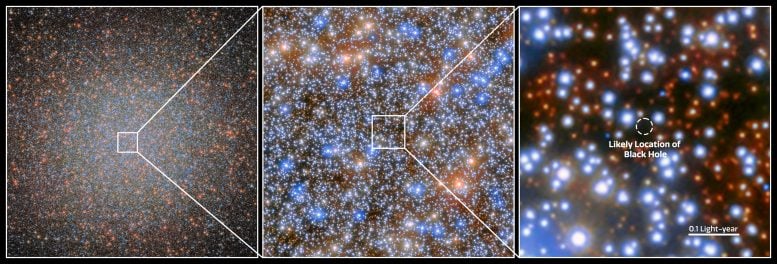

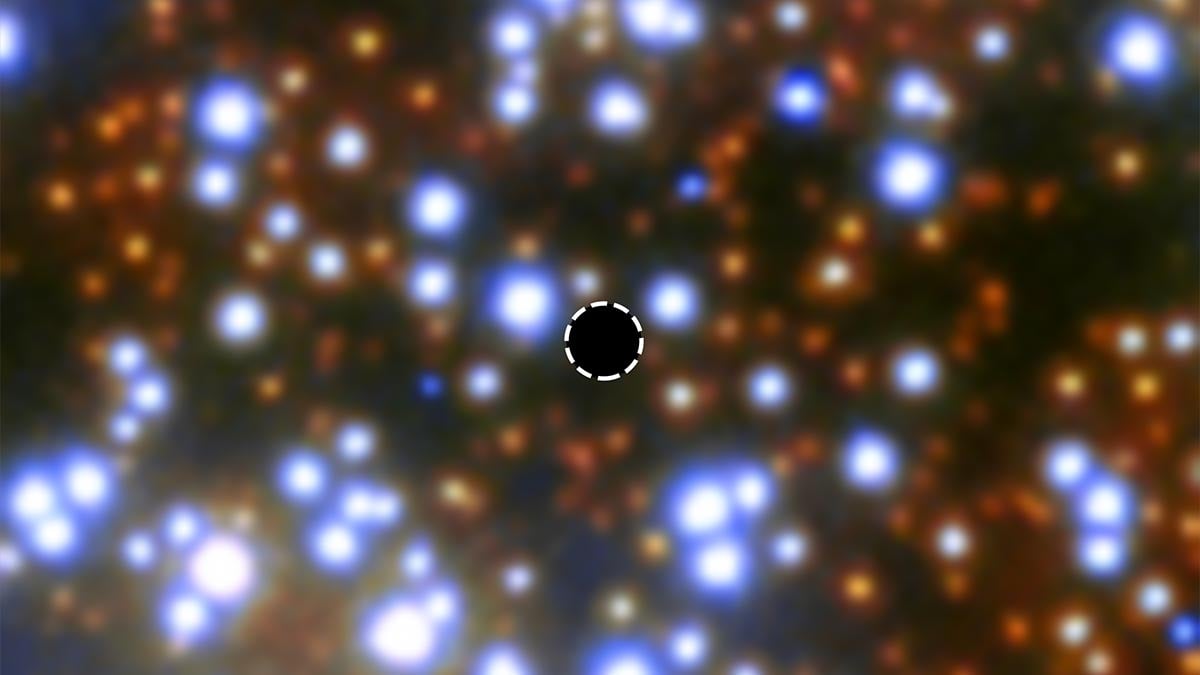

Researchers have confirmed the presence of an intermediate-mass black hole in the center of Omega Centauri, marking a significant discovery in the study of black holes. The black hole, located about 18,000 light-years away, is an important link in understanding black hole evolution, suggesting Omega Centauri might be the core of a dwarf galaxy disrupted by the Milky Way. Credit: ESA/Hubble, NASA, Maximilian Häberle (MPIA)

The discovery is the best candidate for a class of black holes astronomers have long believed to exist but have never found—intermediate-mass black holes formed in early stages of galaxy evolution.

Visible to the naked eye as a smudge in the night sky from Southern latitudes, Omega Centauri is a magnificent collection of 10 million stars. Viewed through a small telescope, it resembles other globular clusters—a densely packed spherical assembly of stars where the core is so congested that individual stars blur into one another.

However, recent research conducted by teams from the University of Utah and the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy has resolved a long-standing debate among astronomers by confirming that Omega Centauri harbors a central

The likely position of Omega Centauri star cluster’s intermediate black hole. From left to right, each panel zooms in closer to the system. Credit: ESA/Hubble, NASA, Maximilian Häberle (MPIA)

Groundbreaking Black Hole Discovery

“This is a once-in-a-career kind of finding. I’ve been excited about it for nine straight months. Every time I think about it, I have a hard time sleeping,” said Anil Seth, associate professor of astronomy at the University of Utah and co-principal investigator (PI) of the study. “I think that extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. This is really, truly extraordinary evidence.”

A clear detection of this black hole had eluded astronomers until now. The overall motions of the stars in the cluster showed that there was likely some unseen mass near its center, but it was unclear if this was an intermediate-mass black hole or just a collection of the stellar black holes. Maybe there was no central black hole at all.

“Previous studies had prompted critical questions of ‘So where are the high-speed stars?’ We now have an answer to that, and the confirmation that Omega Centauri contains an intermediate-mass black hole. At about 18,000 light-years, this is the closest known example for a massive black hole,” said Nadine Neumayer, a group leader at the Max Planck Institute and PI of the study. For comparison, the supermassive black hole in the center of the Milky Way is about 27,000 light-years away.

The paper was published in the journal Nature on July 10, 2024. Watch the research come to life on August 8, 2024, at 7:00 p.m. when Anil Seth will present these once-in-a-lifetime findings at the Clarke Planetarium IMAX theater.

This video shows schematically how Omega Cen was observed with the Diverse Masses of Black Holes

In astronomy, black holes come in different mass ranges. Stellar black holes, between one and a few dozen solar masses, are well known, as are the supermassive black holes with masses of millions or even billions of suns. Our current picture of galaxy evolution suggests that the earliest galaxies should have had intermediate-sized central black holes that would have grown over time, gobbling up smaller galaxies done or merging with larger galaxies. Such medium-sized black holes are notoriously hard to find. Although there are promising candidates, there has been no definite detection of such an intermediate-mass black hole—until now. “There are black holes a little heavier than our sun that are like ants or spiders—they’re hard to spot, but kind of everywhere throughout the universe. Then you’ve got supermassive black holes that are like Godzilla in the centers of galaxies tearing things up, and we can see them easily,” said Matthew Whittaker, an undergraduate student at the University of Utah and co-author of the study. “Then these intermediate-mass black holes are kind of on the level of Bigfoot. Spotting them is like finding the first evidence for Bigfoot—people are going to freak out.” This zoom video begins with an overview of the sky and ends with an image of the Hubble Space Telescope in the center of Omega Centauri. Finally, the orbits of stars around the black hole are shown. Credit: T. Müller (MPIA/HdA), music: K. Jäger (MPIA) When Seth and Neumayer designed a research project to better understand the formation history of Omega Centauri in 2019, they realized they could settle the question of the cluster’s central black hole once and for all. If they found fast-moving stars around its center, they would have the proverbial smoking gun, as well as a way of measuring the black hole’s mass. The arduous search became the task of Maximilian Häberle, a doctoral student at the Max Planck Institute. Häberle led the work of creating an enormous catalog for the motions of stars in Omega Centauri, measuring the velocities for 1.4 million stars by studying over 500 Hubble images of the cluster. Most of these images had been produced for the purpose of calibrating Hubble’s instruments rather than for scientific use. But with their ever-repeating views of Omega Centauri, they turned out to be the ideal data set for the team’s research efforts. “Looking for high-speed stars and documenting their motion was the proverbial search for a needle in a haystack,” Häberle said. In the end, Häberle not only had the most complete catalog of the motion of stars in Omega Centauri yet, he also found seven needles in his archival haystack—seven tell-tale, fast-moving stars in a small region in the center of Omega Centauri. The seven stars move fast because of the presence of a concentrated nearby mass. For a single star, it would be impossible to tell whether it is fast because the central mass is large or because the star is very close to the central mass—or if the star is merely flying straight, with no mass in sight. But seven such stars, with different speeds and directions of motion, allowed the team to separate the different effects and determine that there is a central mass in Omega Centauri, with the mass of at least 8,200 suns. The images do not indicate any visible object at the inferred location of that central mass, as one would expect for a black hole. The broader analysis also allowed the team to narrow down the location of Omega Centauri’s central region at 3 light months in diameter (on images, 3 arc seconds). In addition, the analysis provided statistical reassurance: A single high-speed star in the image might not even belong to Omega Centauri. It could be a star outside the cluster that passes right behind or in front of Omega Centauri’s center by chance. The observations of seven such stars, on the other hand, cannot be pure coincidence, and leaves no room for explanations other than a black hole. Given their findings, the team now plans to examine the center of Omega Centauri in even more detail. The University of Utah’s Seth is leading a project has gained approval to use the DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07511-z “oMEGACat II — Photometry and proper motions for 1.4 million stars in Omega Centauri and its rotation in the plane of the sky” by Maximilian Häberle, Nadine Neumayer, Andrea Bellini, Mattia Libralato, Callie Clontz, Anil C. Seth, Maria Selina Nitschai, Sebastian Kamann, Mayte Alfaro-Cuello, Jay Anderson, Stefan Dreizler, Anja Feldmeier-Krause, Nikolay Kacharov, Marilyn Latour, Antonino Milone, Renuka Pechetti, Glenn van de Ven, Karina Voggel, Accepted, Astrophysical Journal. Other authors include the Max Plank Institute of Astronomy researchers Antoine Dumont, Callie Clontz (also University of Utah), Anja Feldmeier-Krause (also University of Vienna) and Maria Selina Nitschai in collaboration with Andrea Bellini (A Pivotal Finding Through Archival Data

Uncovering a Black Hole

An Intermediate-Mass Black Hole at Last

arXiv:2404.03722

Discussion about this post