Updated at 11:48 a.m. ET on March 11, 2024

Chaos reigns in Alabama—or at least in the Alabama world of reproductive health. Three weeks ago, the state’s supreme court ruled that embryos should be treated as children, thrusting the future of in vitro fertilization, and of thousands of would-be Alabama parents, into uncertainty. Last week, state lawmakers scrambled to pass a legislative fix to protect the right of prospective parents to seek IVF, but they did so without addressing the court’s existential questions about personhood.

Meanwhile, those in the wider anti-abortion movement who oppose IVF are feeling hopeful. Whatever the outcome in Alabama, the situation has yanked the issue “into the public consciousness” nationwide, Aaron Kheriaty, a fellow at the conservative Ethics and Public Policy Center, told me. He and his allies object to IVF for the same reason that they object to abortion: Both procedures result, they believe, in the destruction of innocent life. And in an America without federal abortion protections, in which states will continue to redefine and recategorize what qualifies as life, more citizens will soon encounter what Kheriaty considers the moral hazards of IVF.

In his ideal world, the anti-abortion movement would make ending IVF its new goal—the next frontier in a post-Roe society. The problem, of course, is that crossing that frontier will be bumpy, to say the least. IVF is extremely popular, and banning it is not—something President Joe Biden made a point of highlighting in his State of the Union speech last week. (A full 86 percent of Americans support keeping it legal, according to the latest polling.) “Even a lot of pro-lifers don’t want to touch this issue,” Kheriaty acknowledged. “It’s almost easier to talk about abortion.” But he and his allies see the Alabama ruling as a chance to start a national conversation about the morality of IVF—even if, at first, Americans don’t want to listen.

After all, their movement has already won another unpopular, decades-long fight: With patience and dedication, pro-life activists succeeded in transforming abortion rights from a niche issue in religious circles to a mainstream cause—eventually making opposition to Roe a litmus test for Republican candidates. Perhaps, the thinking goes, pro-lifers could achieve the same with IVF.

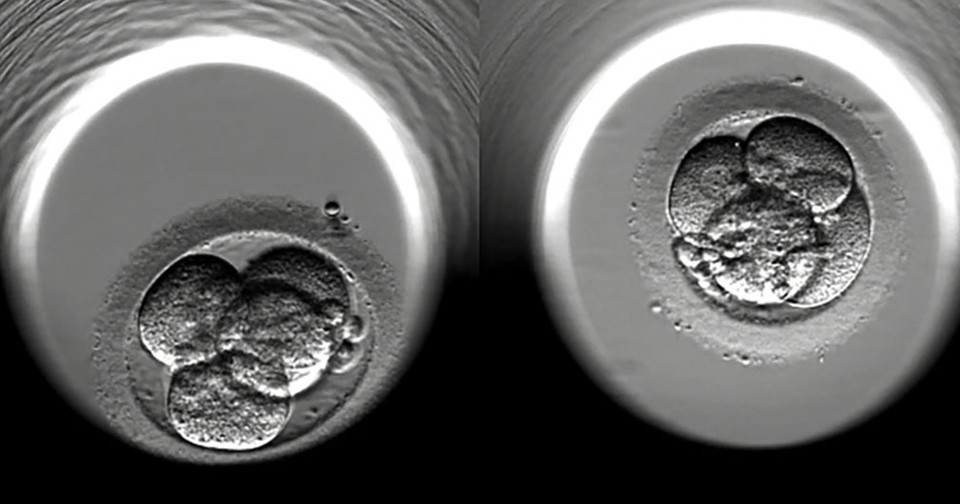

The typical IVF procedure goes like this: A doctor retrieves a number of eggs from a woman’s ovaries—maybe eight to 10—and fertilizes them with sperm in laboratory conditions. The fertilized eggs will grow in the lab for a few days, before one or more embryos will be selected for transfer to the woman’s uterus. A patient using IVF to get pregnant will likely have several embryos left over, and it’s up to the patient whether those extras are discarded, frozen for future use, or donated, either to research or to another couple.

In the Alabama case, three couples were storing frozen embryos at an IVF clinic, where they were mistakenly destroyed. When the couples sued the clinic in a civil trial for the wrongful death of a child, the state supreme court ruled that they were entitled to damages, declaring in a novel interpretation of Alabama law that embryos qualify as children. The public’s response to the ruling can perhaps best be described as panicked. Two of the state’s major in-vitro-fertilization clinics immediately paused operations, citing uncertain legal liability, which disrupted many couples’ medical treatments and forced some out of state for care. Lawmakers across the country raced to clarify their position.

But the ruling shouldn’t have come as such a shock, at least to the pro-life community. After all, “it’s a very morally consistent outcome” with what anti-abortion advocates have long argued—that life begins at conception—Andrew T. Walker, an ethics and public-theology professor at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, told me: “It’s the culmination of other pro-life arguments about human dignity, brought to the IVF domain.”

The central criticism of IVF from Walker and others who share his opinion concerns the destruction of extra embryos, which they view as fully human. For some people, a degree of cognitive dissociation is required to look at a tiny embryo and see a human baby, which is a point that IVF defenders commonly make. (“I would invite them to try to change the diaper of an in vitro–fertilized egg,” Sean Tipton, the chief advocacy and policy officer at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, told me. More soberly, Kate Devine, the medical director of US Fertility, a network of reproduction-focused practices, told me that referring to an embryo as a baby “is unjust and inaccurate and threatens to withhold highly efficacious family-building treatments from people affected by the disease of infertility.”)

To IVF critics, however, an embryo is just a very young person. “The only real difference between those frozen embryos and me sitting here having this conversation with you is time,” Katy Faust, the president of the anti-abortion nonprofit Them Before Us, told me. “If you believe that children have a right to life, and that life begins at conception, then ‘Big Fertility’ as an industry is responsible for more child deaths than the abortion industry.” Faust’s organization argues from a “children’s rights” perspective, meaning it also believes that IVF is wrong, in part, because it allows single women and homosexual couples to have babies, which deprives children of having both a mother and a father.

This leads to the other major criticism of IVF: that the process itself is so unnatural that it devalues sex and treats children as a commodity. The argument to which many religious Americans subscribe is that having children is a “cooperative act among husband, wife, and God himself,” John M. Haas, the president of the National Catholic Bioethics Center, has written. “Children, in the final analysis, should be begotten not made.” The secular version of that opinion is that IVF poses all kinds of thorny bioethical quandaries, including questions about the implications of preimplantation genetic testing and the selection for sex and other traits. When a doctor takes babies “out of the normal process of conception, lines them up in a row, and picks which is the best baby, that brings a eugenicist mindset into it that’s really destructive,” Leah Sargeant, a Catholic writer, told me. “There are big moral complications and red flags that aren’t being treated as such.”

She and the others believe that now is the time to stop ignoring those red flags. The Alabama Supreme Court has offered a chance to teach people about IVF—and the implications they may not yet be aware of. Some couples who’ve undergone IVF don’t even consider the consequences “until they themselves have seven [extra] frozen embryos,” Faust said, “and now they go, ‘Oh, shit, what do we do?’” The more Americans learn about IVF, the less they’ll use it, opponents argue, just as Americans have broadly moved away from international adoption for ethical reasons. Walker would advise faith leaders to counsel couples against the process. “As I’ve talked with people, they’ve come around,” he said.

The IVF opponents I interviewed all made clear that they sympathize with couples struggling with infertility. But they also believe that not all couples will be able to have biological children. “Not every way of pursuing children turns out to be a good way,” Sargeant said; people will have to accept that “you don’t have total control over whether you get one.”

None of these arguments is going to be an applause line for anti-IVF campaigners in most parts of the country. “I know that my view is deeply unpopular,” Walker told me, with a laugh. The Alabama ruling left Republicans in disarray: Even some hard-line social conservatives in Congress, including House Speaker Mike Johnson, have tried to distance themselves from it, arguing that they oppose abortion but support IVF from a natalist position. Democrats, meanwhile, are already using the issue as a wedge: If, in the lead-up to the 2024 election, they can connect Republicans’ support for Dobbs to the possible end of IVF, they’ll have an even easier job painting the GOP as extreme on reproductive health and out of touch with the average American voter.

Even so, the anti-IVF people I interviewed say, at least Americans would be talking about it. Talking, they believe, is the beginning of persuasion. And they’re prepared to be patient.

Earlier this week, Kheriaty texted me with what he seems to take as evidence that his movement is already making progress. He sent a comment he’d gotten from a reader in response to his latest column about the perils of IVF. “This troubling dilemma wasn’t on top of mind when we embarked on our IVF path,” the reader had written. The clinic had explained what would happen to their unused embryos, the woman said, but she hadn’t realized the issue “would loom” so heavily over her afterward.

.png)

Discussion about this post