To make Wealthtender free for readers, we earn money from advertisers, including financial professionals and firms that pay to be featured. This creates a conflict of interest when we favor their promotion over others. Read our editorial policy and terms of service to learn more. Wealthtender is not a client of these financial services providers.

➡️ Find a Local Advisor | 🎯 Find a Specialist Advisor

Sometimes, you write something intended to help people with one thing, but it floats an unexpected objection.

That’s exactly what happened to me with a recent piece: 7 Best Ways You Can Use Excess RMD Money.

Previously, I wrote that one way to avoid or reduce Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) was to convert, e.g., traditional IRAs to Roth IRAs. A reader responded by sharing her painful experience with Roth conversions.

She wrote (lightly edited): “I did large conversions from my 401k to my Roth in 2021 and 2022, congratulating myself on the taxes I expected to save on Roth profits over the 20+ years I expect to live (planning on hitting 100, since my family is long-lived). However, I was hit with several things I did NOT expect.

“1. Because of my large “annual income increase” from the taxable conversion (even though it did not increase my actual income at all), my Social Security income went from being 100% untaxed on Federal and State to 100% TAXED for the next 2 years.

“2. In addition, because of my large “annual income increase” from the conversions, Social Security made large increases in what they charged me for both Part B and Part D insurance. As a result, FOR 2 YEARS, my Social Security income was reduced by a staggering 28%, in addition to it becoming taxable, as mentioned above.

“3. That in turn, of course, forced me to withdraw much more than I expected for living expenses from my retirement savings for 2 years.”

Ouch!

I promised this reader that I’d write about the pitfalls that can snare the unsuspecting Roth converter, so here goes…

Pitfall #1: Social Security Benefits Will Likely Get Taxed

When you do a Roth conversion, the amount you convert is considered taxable income in the year you convert.

If your main source of income is your Social Security retirement benefits, possibly along with minimal other income, you may not expect to pay any taxes.

However, converting a significant amount of IRA money to a Roth can easily boost your taxable income to the point that at least half, and potentially up to 85 percent of your Social Security benefits are suddenly taxable.

The IRS looks at your “combined income,” which is your Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) plus nontaxable interest plus half your Social Security benefit (and if you’re married filing jointly, all these are for both spouses together).

For a combined income of $25k to $34k for individuals or $32k to $44k for married couples filing jointly, half your Social Security benefits become taxable. For combined income above $34k for individuals or $44k for couples filing jointly, 85 percent of your benefits become taxable.

If you’re married and filing separately, it’s a good bet your benefits become taxable.

Pitfall #2: Your Marginal Tax Rate Can Increase

Since the converted amount gets added to your other taxable income, depending on how much you convert that year, you may be pushed into a higher tax bracket, from 10 percent to 12, from 12 percent to 22, from 22 percent to 24, from 24 percent to 32, from 32 percent to 35, or from 35 percent to 37.

If the conversion is large enough, it could potentially push you from 10 percent to as high as 37 (though that’s unlikely as it requires converting over $700k in a single year)!

T. Rowe Price studied when a Roth conversion may make sense from a tax perspective and came up with a mixed bag.

Anthony Ferraiolo, Partner Advisor of AdvicePeriod, shares how he analyzes conversion cases, “We look at changes in the client’s effective tax rate, heirs’ tax brackets, and cash flow constraints. Usually, we aim to ‘fill’ clients’ marginal tax brackets (usually 22% or 24%), but when income is low, you want to check the effective tax on the conversion itself. If that’s close to or higher than the terminal tax bracket, you don’t convert. Another reason not to convert is if you don’t have the excess capital or cash flow to pay the taxes or can’t stomach paying $20k-$30k. I often use a tax budget in Roth conversion analyses to avoid taking money from the conversion or the IRA for taxes, so it typically comes from cash flow or distributions that might happen early in the following year.

“One of my clients (72) has a $300k IRA and five primary beneficiaries. While a conversion would make her IRA tax-free to those heirs, they already have low tax rates (under 24%) and may be in their lowest tax rate period (60-70) when they inherit. Each might only get $60k or $6k/year if distributed over 10 years, unlikely to push up their tax rate.”

Pitfall #3: Increased Medicare Parts B and D Premiums

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) explain how they calculate your Medicare Part B and Part D premiums.

A critical item is the Income-Related Monthly Adjustment Amount (IRMAA).

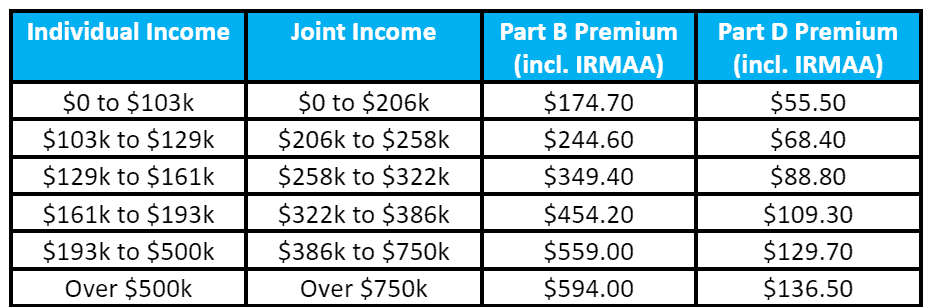

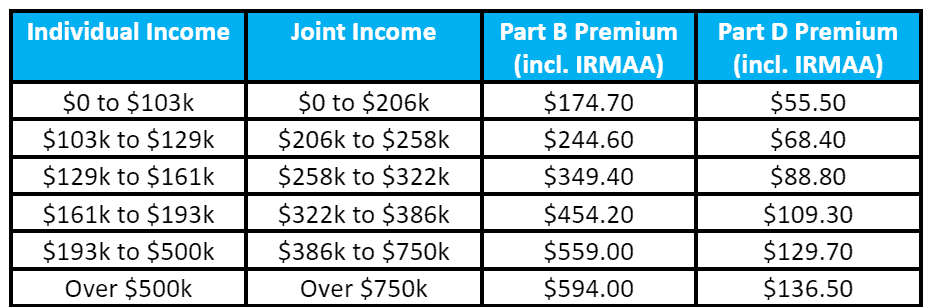

Without IRMAA, the 2024 premiums are $174.70 for Part B and an average of $55.50 for Part D. Using the average for Part D, here’s how the premiums increase due to IRMAA based on your income.

If you were married, lived with your spouse at any time during the year, and filed taxes separately, your IRMAA would jump higher much faster.

As you can see, your Medicare premiums could jump by up to $1000 per month or $12k/year for a couple if your Roth conversion amount is high enough to push you to the highest IRMAA.

Pitfall #4: Delayed Access to the Converted Money

This one isn’t as severe since converting to a Roth implies you want to let the money sit there for many years to get the biggest “bang for the tax buck” you paid.

However, things change, and as the saying goes, “If you want to make G-d laugh, tell him your plans.”

If you do a Roth conversion before you’re 59.5 years old, you must leave the converted money in the Roth account for at least 5 years to avoid the 10 percent penalty. That’s in addition to the other 5-year rule that applies to the age of the account, so this pitfall can get you even if you did the conversion into a long-standing Roth account.

Pitfall #5: The Pro-Rata Rule Can Blindside You

This is an interesting one and the main reason why I can’t use a fun little trick that bypasses the income limits on Roth contributions. That (legal) trick is to contribute after-tax money into a traditional IRA, and then immediately convert it to a Roth IRA.

The problem is that the IRS established the “pro-rata rule.”

This rule says that when you convert from a traditional IRA to a Roth IRA, the determination as to whether the converted dollars have already been taxed isn’t based on the specific IRA account.

Rather, you have to pro-rate the fraction of your overall total after-tax vs. pre-tax dollars across all your IRAs.

For example, say you have a total of $495k in pre-tax dollars in your IRAs. Then, you open a new IRA for your after-tax contribution and put $5k after-tax into it.

If you then convert that new IRA to a Roth IRA, you can’t claim the entire $5k is after-tax. You can only claim 1 percent (the $5k out of the total $500k in all your IRAs) as being after-tax.

You’d owe income tax on the remaining 99 percent!

Pitfall #6: If You Plan to Leave Money to Charity or Expect High Medical Bills, Why Pay Taxes?

As mentioned above, Roth conversions convert money from tax-deferred to tax-free, including any returns on that money, reducing your future taxes or your heirs’ taxes (at the expense of having to pay taxes when you convert).

However, there are situations where paying taxes now for such a conversion doesn’t make sense. For example:

- You plan to leave your IRA(s) to a charity, which is already exempt from paying taxes.

- You plan to make Qualified Charitable Distributions (QCDs) directly from your IRA to a charity.

- You expect to have unusually high medical bills, so even if you take a distribution from your IRA(s), your taxes wouldn’t be especially high because you’ll have a large deduction (medical expenses above 7.5 percent of your AGI are deductible if you itemize).

In these scenarios, you may be better off not converting to avoid the extra current-year taxes.

Pitfall #7: If You Use the QBID, You May Score an “Own Goal”

Suppose you have a “passthrough business” that passes all profits to you as personal income. In that case, you may claim a “Qualified Business Income Deduction” (QBID), of 20 percent of your business income (excludes the salary your business pays you) beyond any business expenses you deduct.

If so, you may or may not be aware that for many businesses, the QBID phases out beyond a certain income level. For 2023 (2024) the QBID starts phasing out if your taxable income is over $232,100 ($241,950) if you’re single, and $464,200 ($483,900) if you’re married filing jointly.

Doing a Roth conversion bumps up your taxable income, potentially by hundreds of thousands of dollars, which could cost you the QBID altogether, effectively increasing your taxes by more than just the regular taxes on the converted amount.

Consider the following scenario:

- Your federal marginal tax rate is 37 percent.

- Your state and local marginal tax rate is 8.25 percent.

- Your property taxes are over $10k, so you can’t deduct your state and local tax from your federal taxable income.

- Your QBID (if you don’t hit the income limit) is $30k.

- You convert $200k from a traditional IRA to a Roth.

Your total income taxes on the conversion is $90,500 (37 percent plus 8.25 percent of $200k).

However, your conversion makes your taxable income too high, so you pay income taxes on the $30k that’s no longer deductible as QBID, adding another $13,575 to your total tax bill.

That makes your effective tax rate on the conversion over 52 percent!

Two Bonus Pitfalls from Financial Pros

I asked financial pros for their best advice on possible pitfalls from Roth conversions, and they came through with a couple more…

Terry Parham Jr, Founder, Innovative Wealth Building, says, “Viewed in isolation, Roth Conversions almost always sound like a good idea. Seriously, who doesn’t like the idea of building up a nest egg of tax-free dollars that can be spent in the future? Like all things, the devil here is in the details. Clients need to be aware of the potentially negative side effects that can result from these well-intentioned strategies so there are no unexpected consequences. One of the basic things to be aware of is tax implications. In addition to federal and state taxes, clients under age 59.5 face a penalty if they withhold from the conversion to pay the taxes.

Parham then adds a pitfall, “If a client is currently paying for college (or will be soon), a Roth conversion could increase their Expected Family Contribution (EFC) due to additional income as a result of the conversion, hurting their chances of getting financial aid.”

Cody Lachner, founder of Next Adventure Financial, shares another possible pitfall, “I’ve had clients who retired early and experienced a large drop in income. Their new lower income allowed them to benefit from tax credits to help cover the cost of health insurance purchased through their state’s health insurance marketplace.

“Normally, Roth conversions are a no-brainer in these low-income years, especially before Social Security begins. However, in these specific situations, the additional income generated by Roth conversions would’ve greatly reduced their premium tax credits. The tax credit loss combined with their marginal tax rate produced a higher effective marginal tax rate than their expected future tax rate. Situations like this are why it’s crucial to review your tax plan year by year to consider all outcomes.”

The Bottom Line

Roth conversions can save you and/or your heirs a lot in taxes, but if you’re not careful, there are at least 7 ways (plus a couple of bonus traps) they could cause you significant financial pain instead. And as you can see, people do run afoul of these pitfalls.

Have a Question to Ask a Financial Advisor?

➡️ Submit your question, and it may be answered by a financial advisor in an upcoming article or in the Expert Answers Forum on Wealthtender.

Additional Find-an-Advisor Resources:

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only, and should not be considered financial advice. You should consult a financial professional before making any major financial decisions.

About the Author

Opher Ganel, Ph.D.

My career has had many unpredictable twists and turns. A MSc in theoretical physics, PhD in experimental high-energy physics, postdoc in particle detector R&D, research position in experimental cosmic-ray physics (including a couple of visits to Antarctica), a brief stint at a small engineering services company supporting NASA, followed by starting my own small consulting practice supporting NASA projects and programs. Along the way, I started other micro businesses and helped my wife start and grow her own Marriage and Family Therapy practice. Now, I use all these experiences to also offer financial strategy services to help independent professionals achieve their personal and business finance goals. Connect with me on my own site: OpherGanel.com and/or follow my Medium publication: medium.com/financial-strategy/.

Learn More About Opher

Discussion about this post