by Alexa Spencer

Dr. Kaia Niambi Shivers was stuck in Italy in March 2020 at the start of the pandemic when she had an idea: to create a directory of Black farmers.

What started as a small project for her online media boutique, Ark Republic, quickly grew into a list of over 1,000 Black farmers and growers worldwide.

Even though she hoped the Black Farmers Index (BFI) would become a resource during a time of global food insecurity, initially the Philadelphia resident didn’t get much support when it launched in April 2020.

“People were like, ‘Oh, that’s cool. That’s cute.’ And then [the murder of George Floyd] happened, and everybody and their mama wanted to be on the right side of history,” Shivers says.

Now, two years later, the Black Famers Index features a variety of farmers and growers from every region of the United States, as well as the U.S. Virgin Islands, Africa, Canada, Central and South America, Europe, and the Caribbean.

“We have beekeepers. We have people who forage for mushrooms. We have cotton producers, oystercatchers, fisher folk, ranchers, [and] poultry farmers. We even have people who grow nuts and rice. And so, it runs the gamut,” Shivers told Word In Black in a video interview.

Who Went Hungry During the Pandemic

As a New York University liberal arts professor teaching in Florence at the time, Shivers was moved to start the index after noticing that, similar to America, low-income residents had the least access to the food supply during the pandemic — even though some of them farmed for a living.

“It was a sad irony that the people who are in the growing industry can’t even afford the food that they pick,” she says.

She suspected that back home in the States, Black people would also be hit hardest by food shortages. She was right.

Black households were already struggling to access food before the pandemic. But in 2020, 21.7% of Black households experienced food insecurity, compared to 17.2% of Hispanic and 7.1% of white households, according to the Center for American Progress.

Shivers and her team got to work to build a pipeline to Black farms. They started with a list of just 150 growers.

By the end of that year, they were packaging holiday gift baskets featuring organic jam, honey jars, supreme Tanzanian coffee, dehydrated oranges, salt blends, walnut butter, and more — all produced by Black growers.

A Date Farmer Joins the Index, Sees Big Growth

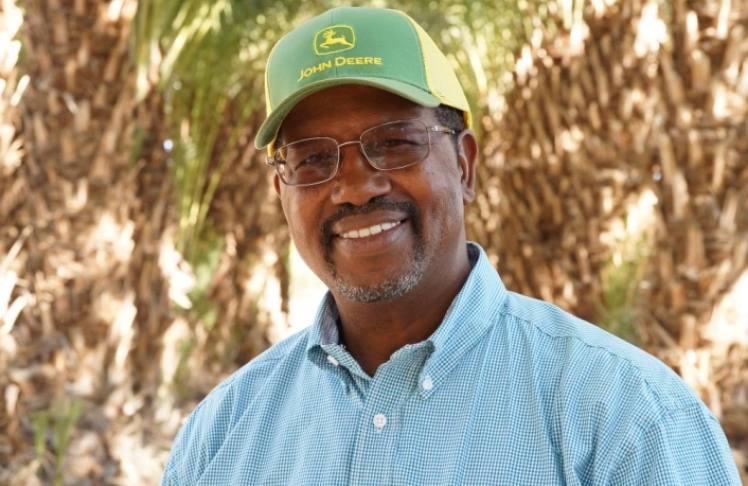

The index has helped growers grow their businesses. Sam Cobb, who grows dates in Blythe and Sky Valley, California, saw exponential growth following an encounter between Shivers and a woman in the Middle East.

Shivers was offered dates in Abu Dhabi while visiting an NYU campus — a custom in that region. But having already tasted dates from Cobb’s Riverside County, California-based farms, she wasn’t satisfied with dates in the capital city of the United Arab Emirates.

“I told one woman, I said, ‘I’m not trying to hate, but I know a man who makes some good dates,’” Shivers says.

The woman then contacted Cobb and ordered over $1,000 worth of product. Cobb says the purchase made him want to grow even better dates.

“I was rather impressed because the Middle East is the land of dates, yet my dates are going to the land of dates,” he told Word In Black in a phone interview.

Not all farmers are as fortunate. Cobb himself experienced financial challenges when initially starting a farm in 1982.

“Farming is serious business. And I know because I went bankrupt trying to just do regular farming,” he says.

After a few years, he found himself in his mother’s backyard, praying under a tree, when God told him, “Sam, you have to sell your own stuff. You have to control the market.”

It took Cobb 30 years to do it, but after working for the United States Department of Agriculture as a soil conservationist, he’s become the only Black date farmer in the U.S.

“Since I grow it, my customers receive the absolute best dates on the market,” he says.

Cobb’s farms grow seven types of dates, including Medjool, Safari, and his very own copyrighted creation, Black Gold.

Cobb says he’s doing what he always wanted to do. When asked how he knew farming was his calling as a child, he says, “It was just in me.”

The BFI team has found other creative ways to help communities get fed and farmers get paid.

Early on, they started “Black Farmer and a Chef,” an initiative that pairs chefs with farmers who supply them with food.

They also hosted “Soil to Shelf,” a free four-part workshop series that provided farmers with marketing tips where they sharpened their customer service skills and learned to promote their farms on social media.

“The reason why we did it was because a lot of the farmers are either left out of a lot of the marketing initiatives, don’t know how to get into the marketing initiatives, or don’t have the business know-how,” Shivers says.

Cobb and his wife, Maxine, found the workshops to be helpful.

“Marketing is everything…If we can’t sell it, there’s no sense in growing it,” Cobb says.

Black Farmers Have Been Harrassed for Too Long

Shivers says the pandemic shed light on many inequities farmers face, including discrimination in the agriculture sector.

After the Biden Administration introduced the Farmers of Color Act — a 2021 bill that addresses historic inequalities by providing farmers of color with debt relief and other resources — Black farmers reported to Shivers that they were being harassed.

But this type of treatment isn’t new. Shivers herself comes from a family of farmers who experienced racial harassment first-hand.

In the early 1900s, her father’s family owned a general depot, a church, and farmland in Vicksburg, Mississippi.

“They had it going on,” Shivers says.

A male family member who was a preacher and spoke out against the incarceration of pregnant Black women was one day accused of doing or saying something inappropriate to a white man.

The local white vigilantes then pursued his family.

“The women, the old folk, and the children fled. The men stayed to defend the land, but nobody made it out. Everybody was either killed, we think, or maybe fled somewhere else, but they were never to be seen,” Shivers says.

Shivers’ mother’s side of the family hails from St. Martinville, Louisiana, and experienced similar trauma.

One day while tilling his land, Shivers’ maternal great-grandfather was approached by a white man who was “known for bullying, as well as getting physical with local Black farmers to get their land.”

The man told her great-grandfather to give him the land before pulling out a gun.

“The gun jammed, and then my grandfather, who was tilling the field with the hoe, hit him with the hoe…and killed him,” Shivers says.

Though he was arrested, her great-grandfather was acquitted after a local priest and a relative of the dead man testified in his favor — but the lynch mob came after him, and he had to run for his life to Texas.

Shivers’ great-grandfather returned 10 years later after hearing stories of his wife and children being terrorized.

“In less than a week, his body parts were found on the train tracks of St. Martinville,” Shivers says.

There could be oil on the land, so Shivers’ family members have been trying to reclaim it, but her maternal grandmother, who died in 2016, called the land “cursed” and said it couldn’t bring back her father.

“These are incidents where land has been stolen, and it has disrupted — severely — the economic trajectory and even the familial trajectory,” Shivers says.

While she wonders who and where she would be if her family had been able to hold on to their land, she finds peace in supporting Black farmers today.

“Black Farmers Index is the healing that my family is doing,”

Shivers says. ”This is my restorative justice work that I need to be doing.”

Discussion about this post