Relocating from one state to another could make a significant difference in whether you receive a dementia diagnosis, regardless of your brain’s actual state of health.

An observational measure of the ‘diagnostic intensity‘ of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias conducted by a team led by the University of Michigan in the US has uncovered a concerning degree of variation in cases between regions across the nation.

Depending on your place of residence, you could be up to twice as likely to qualify as having a serious neurodegenerative condition, especially if you happen to be in your late sixties or early seventies.

Of course different populations will experience higher or lower environmental risks for dementia, and there will always be demographic variations in genetic influences. Yet even when contributing factors are accounted for, a concerning pattern remains.

“These findings go beyond demographic and population-level differences in risk, and indicate that there are health system-level differences that could be targeted and remediated,” says lead author Julie Bynum, a geriatrician and health care researcher from the University of Michigan.

Determining whether an individual’s cognitive decline is caused by a steady loss of neurons requires a battery of tests conducted by medical professionals who operate under a range of laws, guidelines, and recommendations.

While medical definitions may be relatively consistent across county, state, and even national borders, human behavior is anything but predictable. Quirks in regional bureaucracy, individual interpretations of rules and regulations, budgetary decisions, physician beliefs, quality control measures, patient demands … the list of extraneous influences over how tests are administered and interpreted is long and complicated.

Bynum and her team used 4.8 million Medicare claims recorded during 2018 and 2019 to map recent dementia diagnoses across hospital referral regions in the US.

Using statistical models to estimate the number of cases each region should see based on their populations, they calculated each area’s diagnosis intensity – a ratio of actual cases to expected numbers. This was then used to determine how much a person’s regional risk of diagnosis might impact their individual risk of diagnosis.

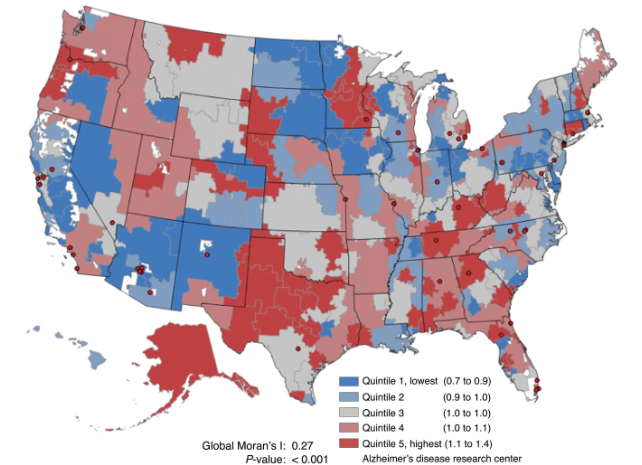

As might be expected, significant differences in the relative number of people diagnosed with ADRD could be seen across the nation, many depending on the spread of sexes, ages, racial distributions, and other healthcare factors.

The diagnosis rate for those aged 66 to 74 was 2 out of every 100 people, for example, compared with 23 per 100 for those over 85. White populations featured a rate of 6.6 percent across referral regions, while Black populations had a rate of 9 percent.

Given that the southern US has the highest concentration of Black people, it’s perhaps not surprising to find the highest unadjusted rate of ADRD cases in the South, especially in states like Texas and Florida.

Taking expected figures into account in measures of actual diagnoses revealed a very different map, from places like Minot North in Dakota having just over two-thirds of the cases they might be expected to have, to Wichita Falls in Texas, with nearly 50 percent more cases than predicted statistically.

“The message is clear: from place to place the likelihood of getting your dementia diagnosed varies, and that may happen because of everything from practice norms for health care providers to individual patients’ knowledge and care-seeking behavior,” says Bynum.

Knowing this variation exists is crucial to ensuring the maximum number of people receive necessary support for their ailing mental health. While an estimated 6.9 million Americans over the age of 65 have a diagnosis of dementia, there are many more who have symptoms of cognitive decline but are yet to have any formal condition recognized.

This not only means they could be missing out on resources that could make their lives easier, but it makes it harder for themselves and their families to prepare for the years ahead.

“For communities and health systems, this should be a call to action for spreading knowledge and increasing efforts to make services available to people,” says Bynum.

“And for individuals, the message is that you may need to advocate for yourself to get what you need, including cognitive checks.”

This research was published in Alzheimer’s and Dementia.

Discussion about this post