Researchers at ETH Zurich have unveiled a new mechanism in the brain that mediates the decision between exercise and snacking. The scientists were surprised to find that a chemical messenger called orexin plays a crucial role in this process. This insight could lead to new, more effective strategies meant to promote physical activity in populations greatly affected by the obesity epidemic.

Orexin: A Decision-Making Chemical

Imagine standing at a crossroads: to exercise or to enjoy a delicious strawberry milkshake? For years, scientists have pondered what happens in our brains at this moment of decision. Now, researchers at ETH Zurich have found at least part of this answer. They identified orexin and the neurons producing it as the key players in this choice.

Unlike other well-known brain messengers like serotonin and dopamine, orexin (also known as hypocretin) was discovered relatively recently, about 25 years ago. Its functions are only now being clarified.

One of orexin’s most fascinating functions is its regulation of the sleep-wake cycle. By promoting wakefulness, orexin helps maintain a stable and alert state during the day. People with narcolepsy often lack orexin-producing neurons, leading to excessive daytime sleepiness and sudden muscle weakness known as cataplexy. Beyond its role in sleep, orexin also influences feeding behavior and energy homeostasis, as well as reward systems and addiction.

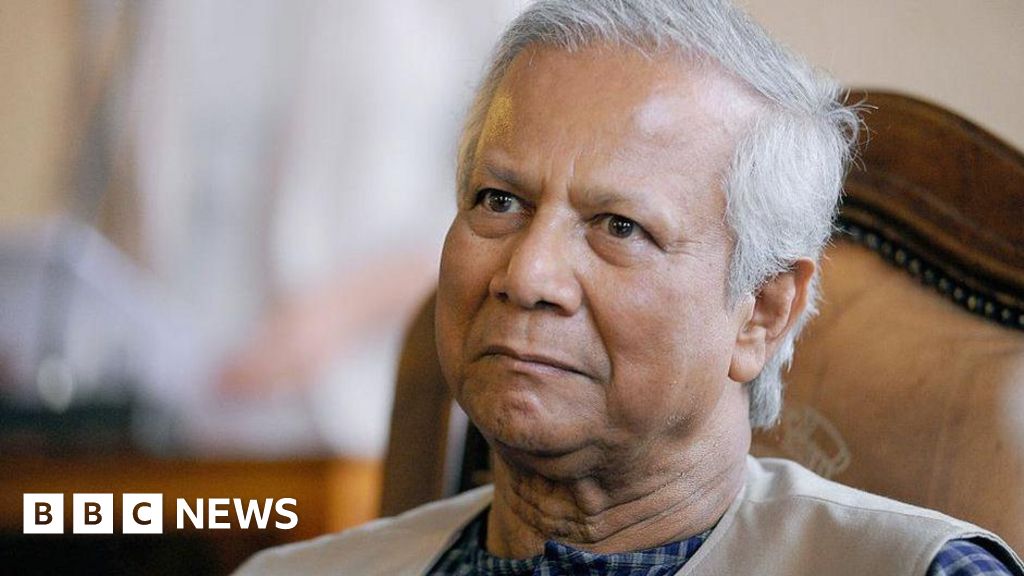

Denis Burdakov, Professor of Neuroscience at ETH Zurich, and his team conducted experiments on mice. The rodents were offered several options, all of which they are known to like: another mouse, different foods, a hiding place, and a “mouse treadmill” (a running wheel).

“We were surprised to find that they were very interested in running on the wheel, when they could eat or socialize instead! Even when we tried to distract them by giving them especially tasty food, they still chose to spend the same time running, rather than make full use of the limited (10 min) food opportunity,” Budakov told ZME Science.

“At first we were rather frustrated by the results, because we were hoping to study something else, but the mice kept jumping onto the treadmill instead!”

However, mice with a blocked orexin system opted more frequently for a milkshake over exercise. This suggests that rather than mediating how much the mice move or eat, orexin seems to control the decision-making process between the two options.

“When given delicious food, they gave up the running wheel to a large extent. Thus we stumbled upon a brain factor responsible for “temptation-resistance voluntary exercise,’” said Budakov.

Denis Burdakov, a Professor of Neuroscience at ETH Zurich, emphasizes the importance of this discovery. “We wanted to know what it is in our brain that helps us make these decisions,” he explains. Orexin is just one of over a hundred messengers active in the brain, but it plays a crucial role in decision-making between physical activity and indulgence.

From Mice to Humans

These findings have significant implications for humans. The brain functions involved in the orexin networks are known to be practically the same in both mice and humans. As such, this discovery could help researchers develop strategies to encourage physical activity, potentially addressing the global obesity epidemic.

According to the World Health Organization, 80 percent of adolescents and 27 percent of adults don’t get enough exercise. Obesity rates are soaring among both adults and children.

The next steps involve verifying these results in humans. This could include examining patients with a restricted orexin system due to genetic reasons or those receiving orexin-blocking drugs for conditions like insomnia.

“There is now a lot of interest in regulating brain orexin activity. Lowering it might help fight disorders such as insomnia. Our study suggests that there are also circumstances where high orexin activity might be beneficial. So developing methods for changing orexin activity in either direction, depending on the patient, could certainly be very useful,” Budakov wrote in an e-mail to ZME Science.

The findings were reported in a new study published in the journal Nature Neuroscience.

Thanks for your feedback!

Discussion about this post