Up until two years ago, the regulation of California’s lawyers was not something many people outside the profession gave much thought. Then the legendary Wilshire Boulevard law firm Girardi Keese collapsed under circumstances that transfixed both the Golden State’s power structure and the nation’s reality TV fans.

Tom Girardi, political influencer and renowned champion of the downtrodden, had been stealing from clients for decades, it emerged in court records and press reports. And his wife, Erika, flaunter of diamonds and couture on “Real Housewives of Beverly Hills,” had been enjoying, perhaps unwittingly, an opulent lifestyle underwritten by cheated clients.

In this evolving melodrama, the spotlight eventually came to rest on a new villain: the State Bar of California, the regulatory agency responsible for licensing 266,000 lawyers and protecting the public from corrupt ones.

“In the past, 0.1% of the California population gave a damn about what the State Bar was doing,” said state Sen. Tom Umberg, the Orange County lawyer who has been chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee since 2018. These days, he said, “community members go, ‘What are you doing about this thing? This is horrible.’”

Revelations about Girardi, many first detailed in The Times, have led to a two-year reckoning at the bar and in the larger legal world. The scandal has compelled top officials at the agency, Sacramento lawmakers and even the chief justice of the state Supreme Court — which oversees the bar — to publicly acknowledge profound failures, especially in investigating the wealthy and well-connected, and to promise change.

“We’ll take the lessons learned from the years and hundreds of Girardi complaints and find a way to have an effective audit that really permits them to go forward with credibility,” said outgoing Chief Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye.

Whether the current mantra of reform will lead to a true turnaround remains to be seen. The bar has pledged to make changes at several junctures over the past few decades and remained fundamentally troubled. Trial lawyers, among the state’s most powerful professional groups, have beaten back new regulations in the past and are expected to lobby against them this time.

“They are breaking down decades of culture, ultimately,” said former Assemblyman Mark Stone, who chaired the Assembly Judiciary Committee until earlier this year and dealt frequently with Bar officials. He said he was cautiously optimistic about the current leadership team. “I’m still a little in the camp of ‘trust, but verify’… I believe what they are telling me but I want to see it happen.”

California Supreme Court Chief Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye.

(Associated Press)

It was a Times investigation in March 2021 that kicked off intense scrutiny of the agency in regards to Girardi. The newspaper detailed how the powerful lawyer cultivated close relationships with investigators and bar executives and showered them with gifts, including private plane rides, boozy lunches at Morton’s, free legal representation and Vegas shindigs.

At the same time, angry clients and colleagues were accusing Girardi in scores of lawsuits of stealing from them. The clients were often vulnerable individuals and families, already claiming injury from toxic pollution, pharmaceutical side effects and negligence. Among Girardi’s victims were Indonesian widows and orphans whose relatives died in the crash of a Boeing airplane.

It ultimately took a petition by The Times to the state Supreme Court — and a nearly two-year legal battle — to dislodge confidential records about his troubled history from the bar. Released this fall, they showed Girardi had been the subject of a jaw-dropping 205 complaints over his career, with more than 150 coming before the bar ever took public disciplinary action against him. While the bar closed case after case with little or no investigation, the attorney kept up his image as a billion-dollar litigator who had the governor on speed-dial and scores of judges eager to attend his lavish parties.

In the wake of the March 2021 story, the agency conducted a review of his file and admitted publicly that there were “mistakes made … going back 40 years.”

The bar’s governing board then hired an outside law firm last year to investigate whether anyone inside the agency had helped Girardi elude discipline. The probe is ongoing and, this fall, bar lawyers went to court to force two former employees who were associates of Girardi — an investigator and an administrative assistant — to comply with subpoenas to answer questions about the handling of complaints.

“Mark our words: we will go wherever the evidence leads us,” Ruben Duran, chair of the State Bar’s board of trustees, said in announcing the investigation.

Exterior of the State Bar of California’s headquarters in downtown Los Angeles.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

In what appeared to be an attempt to push forward reforms, the state Supreme Court appointed Duran, a civil attorney from Ontario, to an unprecedented second one-year term heading the bar board.

Among the strongest steps toward reform was the hiring of a respected former federal prosecutor, George Cardona, who had led the criminal division at the U.S. Attorney’s office in L.A., as chief trial counsel, or top prosecutor.

“One of my overriding goals is to kind of restore confidence in the discipline system,” Cardona said in an interview.

Following his appointment, the bar launched a series of investigations into high-profile lawyers, a startling departure from the timidity the agency often displayed in the past.

Prominent L.A. lawyers Brian Kabateck, left, and Mark Geragos.

(Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

After The Times detailed the mishandling of money in a class-action settlement on behalf of victims of the Armenian genocide, Cardona took the rare step this fall of publicly announcing an investigation of two prominent L.A. lawyers, celebrity defense lawyer Mark Geragos and former L.A. County Bar Assn. president Brian Kabateck. Both have denied wrongdoing.

In July, the State Bar unveiled charges against its former chief executive, Joe Dunn, who was fired in 2014 after an internal investigation raised questions about his close ties to Girardi. The charges stem from his time at the bar and falsehoods he allegedly made about expenses for overseas travel with two Girardi associates. He has denied wrongdoing.

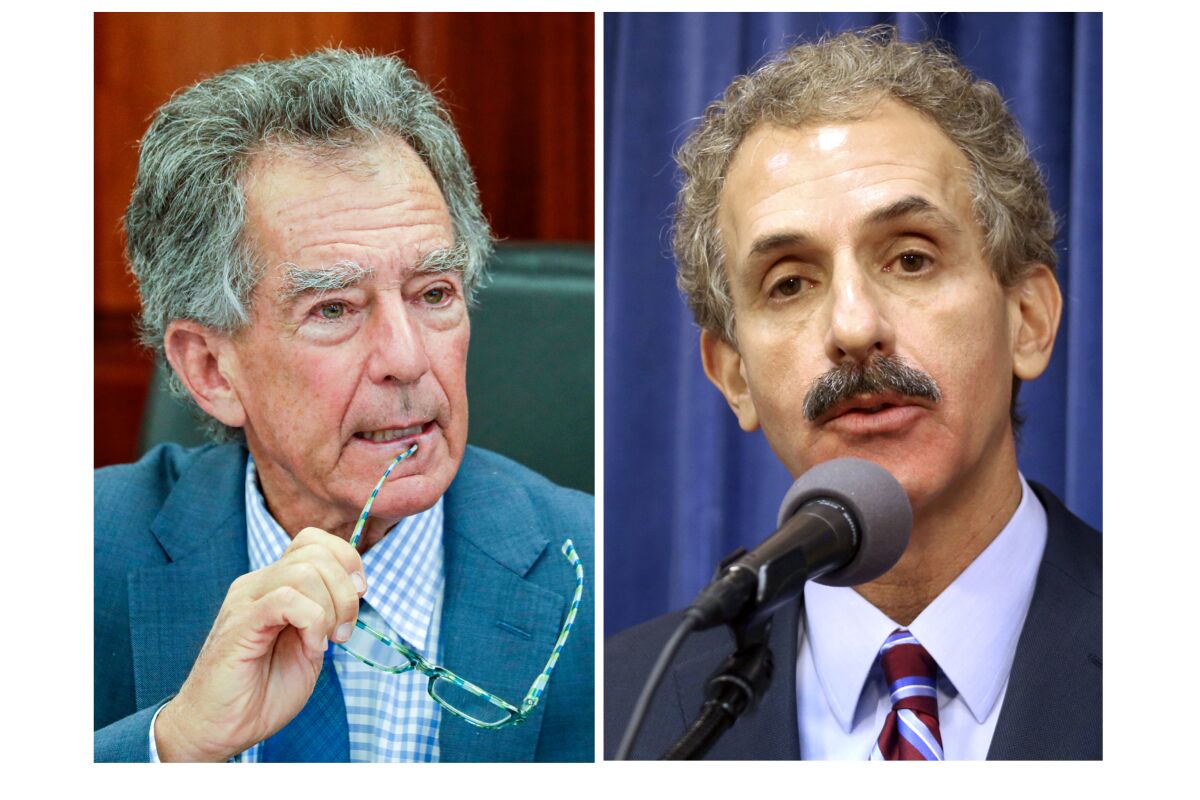

The agency also has an ongoing probe of former L.A. City Atty. Mike Feuer and others in connection with an extortion and collusion scheme involving lawyers at the Department of Water & Power. Paul Paradis, who served as special counsel for the DWP and pleaded guilty to bribery earlier this year, wrote in a bankruptcy court filing that he is cooperating with Cardona’s office in investigations of at least 10 DWP-connected attorneys initiated this year. He said they include Feuer and former congressman and DWP commissioner Mel Levine. Feuer confirmed the investigation, adding, “I’m completely confident they will determine there’s no issue here.” Levine said the bar has not informed him that he’s under investigation.

Former congressman Mel Levine, left, and Los Angeles City Atty. Mike Feuer.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times, Mike Balsamo / Associated Press)

And this month, the bar filed charges against Girardi’s former law partner, Richard Crane, a retired prosecutor who once headed the Department of Justice organized crime strike force for the western U.S. Crane is accused of improperly collecting a $100,000 retainer and failing to issue a refund or accounting to his client. “I totally dispute the State Bar charges,” Crane said in an email, promising to disprove the charges at a future hearing.

Cardona’s office has also embarked on a review of what officials have called “frequent flier” lawyers, a group of attorneys who have not been publicly disciplined despite numerous complaints.

Robert Fellmeth, a University of San Diego law professor who previously served as an outside monitor for the agency, was tapped to review those files, which he said fill 28 boxes.

“If you have someone with 20 or 30 or 40 or 50 allegations, even if they are middling allegations, that should cause you to take action and that has not been happening. And that’s very frustrating,” he said.

Fellmeth drew up recommendations to improve discipline, which could be adopted as soon as next year. Among them is a proposal that the bar assign a special supervisor to handle attorneys with more than five pending “significant” complaints or 15 complaints in general.

Another possible reform is a mandatory reporting rule for lawyers. The Times reported this fall that California is the only state that does not have a statute requiring or encouraging attorneys to alert regulators to misconduct by their peers. Recently Umberg, the state senator from Orange County, put forth a bill that would bring the state in line with other jurisdictions. Bar leadership said it supported the measure.

There is also a push to regulate the growing field of private judging and mediation, prompted by Girardi’s relationship with those judges and mediators. As the Times reported this summer, he relied on retired jurists as he misappropriated client money and traded on these judges’ reputations to deflect suspicion.

Cantil-Sakauye, the outgoing chief justice, called The Times’ report “shocking” and, in a recent news conference, reiterated her call for the State Bar “to regulate, oversee, [and] discipline mediators.”

“Mediators are lawyers,” Cantil-Sakuye said, and thus under the bar’s authority. “There ought to be a focus on mediation and mediators, [with] training, qualifications and a complaint process specifically for that.”

The bar has already implemented new rules for lawyers’ handling of client money in response to Girardi’s delays in paying out and misappropriating settlement money. Starting this month, attorneys have to disclose and register their client trust accounts to the bar and certify that the accounts are in compliance with bar rules. A new statute requires attorneys to notify clients within two weeks of deposits of settlement money. Girardi delayed months and even years in passing on settlement funds.

Carol Langford, a Bay Area specialist in the defense of accused lawyers, said she has received “frantic calls” about the new rules.

“I’m getting inquiries from people who are telling me, ‘I’m not in compliance and haven’t been,’” Langford said. She said the rules were “something they are passing to look good” and wouldn’t have prevented the Girardi scandal, but acknowledged, “I think a good 40% of people are out of trust and not doing it right.”

The bar’s investigation into whether agency insiders helped Girardi elude discipline is ongoing, and officials have not revealed any of their findings. Stone, who chaired the Assembly Judiciary Committee until this fall, said he was disappointed that the agency had not updated legislators on the investigation’s progress.

“Those are the kinds of things that need to happen to build back trust,” Stone said. “They have erred on the side of everything being confidential as a way of hiding malfeasance or bad actions for such a long time. Maybe they need to err on the side of openness.”

Even with more transparency and reforms, many at the bar say that real change requires a significant funding increase. The budget for the agency’s discipline system comes almost entirely from the annual fees lawyers pay. The legislature must approve any hike to the fees and lawmakers have rebuffed attempts to dramatically raise them in part because of the bar’s shortcomings.

The dues for next year are $510 for active attorneys. Fellmeth said that the fees have not been raised to keep up with inflation, let alone expand the ranks of investigators and prosecutors, and that a well-functioning disciplinary arm would mean annual fees of “about $800.”

Few think Sacramento, where many are still furious about Girardi, will approve anything close to that.

Leah Wilson, executive director of the State Bar of California.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

“We’re so woefully underfunded for what we are being asked to do,” said the bar’s executive director, Leah Wilson. “But I personally don’t see a pathway at this juncture for us to secure a licensing fee increase, no matter how much it’s needed, because the trust in our system isn’t there.”

Another option is for the Legislature to send an infusion of taxpayer money — perhaps as much as $10 million to $20 million — from the general fund to boost the discipline system. Fellmeth argued that such a one-time outlay of money could allow the bar to hire qualified staff who could provide effective enforcement, weeding out the attorneys hurting clients and the administration of justice in general. Over time, he said, that would improve the entire court system in California, which runs largely on taxpayer funds.

“If [the court system] doesn’t have competent lawyers,” Fellmeth said, “you’re gonna be wasting a lot of the general fund money.”

Discussion about this post