The recent resurgence of the Rwanda-backed M23 rebels in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) demands comprehensive political negotiations among all the many local and regional players contributing to the crisis in that territory – and not just more military interventions, says Great Lakes expert Stephanie Wolters.

Since fighting between DRC government troops and the long-dormant M23 flared up again in late 2021, over 602,000 Congolese civilians have been displaced in the province of North Kivu alone, said Wolters, a senior researcher at the South African Institute of International Affairs, in an online briefing last week.

The strong revival of the M23 almost a decade after a force of soldiers from the Southern African Development Community (SADC) defeated it, prompted SADC to decide last month to deploy yet another military force into the chronically turbulent eastern DRC.

Too many players

The new SADC force would join an already crowded field of regional and international actors who have so far barely dented the instability.

“This is a lot of players in a small space with no clear mandate,” said Wolters. “A military solution is not going to resolve this. And it’s not even clear that a military victory is possible.”

Instead of more boots on the ground, she proposed a series of dialogues among the many players involved.

The United Nations peacekeeping force, Monusco, and its robust Force Intervention Brigade (FIB) – staffed by soldiers from SADC member states South Africa, Tanzania and Malawi – as well as an East African Community Regional Force (EACRF), are already deployed in eastern DRC, supposedly fighting the M23 and the many other armed rebel groups which have been terrorising local communities for many years.

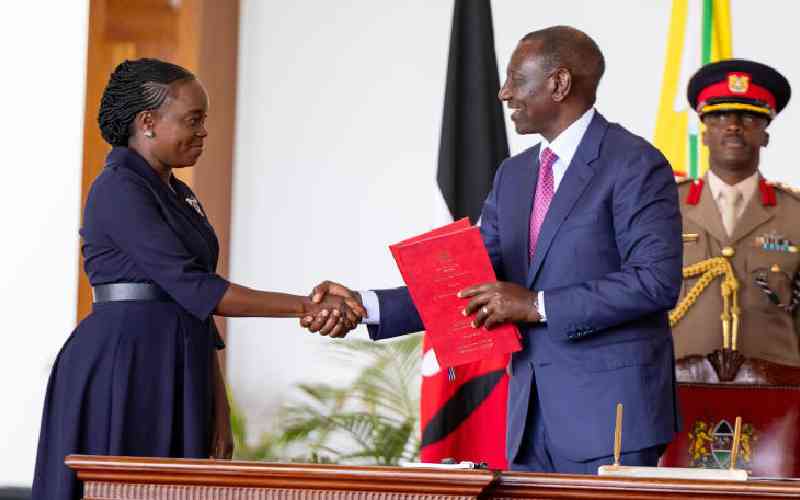

SADC’s decision in Windhoek on 8 May this year to deploy yet another force was evidently at the behest of DRC President Felix Tshisekedi.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Success of East African Community peace process hinges on regional coordination on eastern DRC conflict

The DRC, already a member of SADC, last year also joined the East African Community (EAC) and soon after that, the EAC agreed to Tshisekedi’s request to deploy a military East African Regional Force to eastern DRC.

Ugandan, Burundian, Kenyan and South Sudanese troops began arriving in November 2022, and by April this year, the EACRF was fully deployed.

But Tshisekedi has clashed with the EAC over the EACRF’s mandate. He says it must tackle the resurgent M23 armed group, representing ethnic Tutsi Congolese, which he has openly accused Rwanda of backing. But the EACRF has been reluctant to do that, probably because its members have interests in eastern DRC.

Wolters thought William Ruto’s victory in last year’s Kenyan elections may have been crucial in the EAC’s apparent change of heart. Tshisekedi was close to former President Uhuru Kenyatta, but is not close to Ruto.

Failing to get satisfaction from the EAC, Tshisekedi turned instead to the SADC to deploy a force which he hoped would seriously tackle M23. So history seems to be repeating itself. Ten years ago, the FIB helped the DRC drive the M23 out of the DRC. Now it is back again, even stronger militarily and occupying more territory than in 2012-2013, Wolters said.

Though Rwanda has once again denied it, as it did in 2012-2013, a UN Panel of Experts confirmed in a report last December that Rwanda is once again backing the M23. And Wolters said the M23 also presents a bigger threat now because this time the international community has taken no action against Rwanda, unlike in 2013 when several Western countries suspended development aid.

President Paul Kagame is now playing a smarter game of making himself indispensable to foreign donors, through his deal to accept unwanted asylum seekers from the UK and by deploying soldiers to beat Islamist violent extremists in Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado provinces, paving the way for the French company TotalEnergies to return to its gas processing plant at Afungi.

A group of M23 rebel fighters leave the city aboard a truck in Sake, some 20km west of Goma, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, 30 November 2012. (Photo: EPA / DAI KUROKAWA)

Stalled negotiations

There are also regional negotiation efforts, Wolters said. The EAC was chairing negotiations in Nairobi between Kinshasa and several domestic armed DRC rebel groups last year. The M23 had originally been involved but Tshisekedi had forced them out because he said they had broken an agreement to retreat to their March 2022 positions.

Wolters said the Nairobi talks had made no tangible progress, partly because they had a vague agenda and partly because many armed rebel groups were not involved.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Eastern DRC peace processes falling short of the mark due to inconsistency and poor regional cooperation

Wolters noted that the African Union had tasked Angolan President Joao Lourenço, as the current chairperson of the International Conference of the Great Lakes Region, to mediate direct negotiations between DRC and Rwanda to try to resolve the rising tensions between them over the M23.

She said these talks had also achieved little. The M23, for instance, had ignored an agreement to retreat to its March 2022 military positions.

She recalled that security in eastern DRC had plummeted after about two years of relative stability. After Tshisekedi took over from Joseph Kabila in early 2019, he made a strong effort to mend the DRC’s fraught relations with its neighbours Rwanda and Uganda, which have been meddling in eastern DRC for nearly three decades.

Kagame, for instance, had accepted an invitation to pay a very rare visit to Kinshasa to attend the funeral of Tshisekedi’s father, Etienne. Tshisekedi had also launched joint economic projects with Rwanda and Uganda to cement regional integration, such as joint gold smelters, other mining deals and tax agreements.

Tshisekedi and Museveni also launched a joint venture to build a road running down the DRC side of the border from Bunagana near the Uganda border, south to Goma on the Rwanda border.

M23 rebel fighters stand on a hill overlooking Lake Kivu near the frontline town of Kirotshe, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, 30 November 2012. (Photo: EPA / DAI KUROKAWA)

Building tension

“So how did we get from there … in two years … to probably the worst security crisis in a long time?” Wolters asked.

The answer was in part that Tshisekedi’s attempts at reconciliation backfired badly. Kagame clearly felt that the DRC’s road construction with Uganda was trespassing on what he regarded as his “forecourt” in eastern DRC.

Wolters thinks he also didn’t like the DRC’s agreement with Kampala for Ugandan troops to enter the DRC in joint pursuit of the Allied Democratic Forces, an Islamic State-affiliated armed group which originated in Uganda but is now viciously terrorising the Congolese.

Conversely, Tshisekedi terminated an equivalent arrangement which had allowed Rwandan troops to enter eastern DRC to pursue the armed rebels of the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) which had been founded by Hutu extremists who fled Rwanda after participating in the genocide.

The DRC joining the EAC was the final straw.

“That accession pushed Kagame. I think it was just too much. Too many things, too many actions, too many developments he couldn’t control in an area Rwanda considers vital to its security and economic future,” Wolters said.

And so Kagame once again threw his weight behind the M23.

Kagame denies Rwanda is supporting the M23 and claims instead that DRC is supporting the FDLR. Fighting the FDLR has long been Rwanda’s pretext for entering eastern DRC. But Wolters said that while the FDLR might have been a real threat to Rwanda 20 years ago, it had been considerably weakened by the military operations against it and the voluntary return of over 10,000 of its fighters to Rwanda.

Its force was now estimated at fewer than 500-1,000; hardly a huge threat.

Wolters felt it simply came down to Kagame “feeling he has a right to do what he likes in the eastern DRC”, deriving many benefits, including gold smuggling and being able to fight his enemies.

“And there have been almost no consequences for him over the last 20 years,” she notes.

In a recent speech in Benin, Kagame had even questioned the colonial borders separating the DRC and Rwanda, she said, implying that he thought the eastern DRC was really Rwanda’s.

Paths to peace

Wolters proposed a raft of parallel negotiations to tackle the chronic eastern DRC crisis.

First, Tshisekedi should reverse his refusal to negotiate directly with the M23, even if he felt they were a proxy for Rwanda. One aim would be to implement the broken promises of the 2013 Kampala peace accords which ended the last M23 insurgency, particularly the agreement to integrate M23 rebels into the DRC military.

Tshisekedi should also engage in separate discussions with Kagame about Rwanda ending its support to the M23. Conversely, the DRC should address the safety of Congolese Tutsi refugees and break off all associations with the FDLR.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Great Lakes mediation critical to prevent the eruption of full-scale war between Rwanda and the DRC

The AU, with strong support from the UN, should launch a third discussion among all regional leaders to remove the long-term drivers of instability in the Great Lakes region, such as the regional rivalries, economic incentives for instability, security challenges, economic tensions and the exploitation of the DRC’s natural resources by neighbouring states.

Finally, Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi should begin to address their own domestic political challenges by engaging in talks with the respective armed groups opposing them from eastern DRC.

This would allow the DRC to focus on its own armed rebel enemies and would be a vital element in returning the Great Lakes to long-term, sustainable peace.

If this happened, the M23 resurgence would become an opportunity to finally address the deep drivers of eastern DRC’s chronic instability, Wolters said. DM

![]()

Discussion about this post