Pedestrians walk past a billboard announcing the World Bank Group and International Monetary Fund annual meetings, on the side of the International Monetary Fund headquarters in Washington DC on October 5, 2023.

Mandel Ngan | Afp | Getty Images

Top economists and central bankers appear to be in agreement on one thing: interest rates will stay higher for longer, clouding the outlook for global markets.

Central banks around the world have hiked interest rates aggressively over the past 18 months or so in a bid to rein in soaring inflation, with varying degrees of success thus far.

Before pausing its hiking cycle in September, the U.S. Federal Reserve had lifted its main policy rate from a target range of 0.25-0.5% in March 2022 to 5.25-5.5% in July 2023.

Despite the pause, Fed officials have signaled that rates may have to remain higher for longer than markets had initially expected if inflation is to sustainably return to the central bank’s 2% target.

This was echoed by World Bank President Ajay Banga, who told a news conference at the IMF-World Bank meetings last week that rates will likely stay higher for longer and complicate the investment landscape for companies and central banks around the world, especially in light of the ongoing geopolitical tensions.

U.S. inflation has retreated significantly from its June 2022 peak of 9.1% year-on-year, but still came in above expectations in September at 3.7%, according to a Labor Department report last week.

“For sure, we’re going to see rates higher for longer and we saw the inflation print out of the U.S. recently which was disappointing if you were hoping for rates to go down,” Greg Guyett, CEO of global banking and markets at HSBC, told CNBC on the sidelines of the IMF meetings in Marrakech, Morocco last week.

He added that concerns around persistently higher borrowing costs were resulting in a “very quiet deal environment” with weak capital issuance and recent IPOs, such as Birkenstock, struggling to find bidders.

“I will say that the strategic dialog has picked up quite actively because I think companies are looking for growth and they see synergies as a way to get that, but I think it will be a while before people start pulling the trigger given financing costs,” Guyett added.

The European Central Bank last month issued a 10th consecutive interest rate hike to take its main deposit facility to a record 4% despite signs of a weakening euro zone economy. However, it signaled that further hikes may be off the table for now.

Several central bank governors and members of the ECB’s Governing Council told CNBC last week that while a November rate increase may be unlikely, the door has to remain open to hikes in the future given persistent inflationary pressures and the potential for new shocks.

Croatian National Bank Governor Boris Vujčić said the suggestion that rates will remain higher for longer is not new, but that markets in both the U.S. and Europe have been slow in repricing to accommodate it.

“We cannot expect rates to come down before we are firmly convinced that the inflation rate is on the way down to our medium-term target which will not happen very soon,” Vujčić told CNBC in Marrakech.

Euro zone inflation fell to 4.3% in September, its lowest level since October 2021, and Vujčić said the decline is expected to continue as base effects, monetary policy tightening and a stagnating economy continue to feed through into the figures.

“However at some point when inflation reaches a level, I would guess somewhere close to 3, 3.5%, there is an uncertainty whether, given the strength of the labor market and the wage pressures, we will have a further convergence with our medium-term target in a way that it has been projected at the moment,” he added.

“If that does not happen then there is a risk that we would have to do more.”

This caution was echoed by Bank of Latvia Governor and fellow Governing Council member Mārtiņš Kazāks, who said he was happy for interest rates to stay at their current level but could not “close the door” to further increases for two reasons.

“One is of course the labor market — we still haven’t seen the wage growth peaking — but the other one of course is geopolitics,” he told CNBC’s Joumanna Bercetche and Silvia Amaro at the IMF meetings.

“We may have more shocks that may drive inflation up, and that’s why of course we have to remain very cautious about inflation developments.”

He added that monetary policy is entering a new “higher for longer” phase of the cycle, which will likely carry through to ensure the ECB can return inflation solidly to 2% in the second half of 2025.

Also at the more hawkish end of the Governing Council, Austrian National Bank Governor Robert Holzmann suggested that the risks to the current inflation trajectory were still tilted to the upside, pointing to the eruption of the Israel-Hamas war and other possible disturbances that could send oil prices higher.

“If additional shocks come and if the information we have proves to be incorrect, we may have to hike another time or perhaps two times,” he said.

“That’s also a message given to the market: don’t start to talk about when will be the first decrease. We’re still in a period in which we don’t know how long it will take to come to the inflation we want to have and whether we have to hike more.”

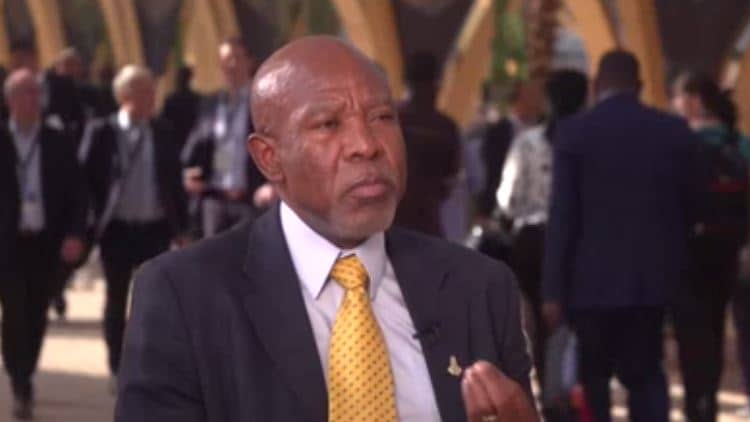

For South African Reserve Bank Governor Lesetja Kganyago, the job is “not yet done.” However, he suggested that the SARB is at a point where it can afford to pause to assess the full effects of prior monetary policy tightening. The central bank has lifted its main repo rate from 3.5% in November 2021 to 8.25% in May 2023, where it has remained since.

Discussion about this post