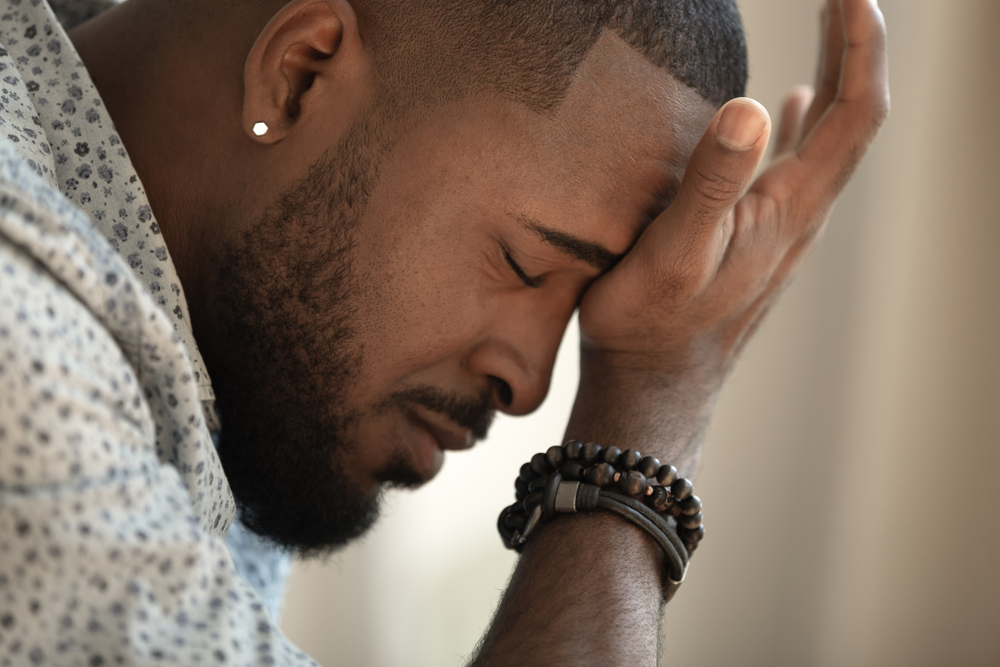

It goes by many different names: rumination, repetitive negative thinking, negative thought syndrome, spiraling thoughts. But whatever you call it, it can have damaging consequences for your mental health.

The experience — let’s call it rumination — can include dwelling on past mistakes or worrying about future events or decisions you’ll have to make. While reviewing and learning from the past and preparing for the future are healthy (even necessary) mental processes, rumination is something different.

With rumination, the thoughts are not constructive or helpful. Instead, they focus on the negative and often distort the facts, making the situation seem more dismal than it really is. Rather than help you process emotions and develop better responses to life, rumination can create or worsen emotional problems.

A Negative Mental Filter

“When I think of rumination, I think of it as being these repetitive thinking mistakes, like catastrophizing a situation or having a negative mental filter that you don’t notice,” says Maggie Canter, clinical psychologist and assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

“Often people get so stuck in these thoughts that they don’t notice when their circumstances are changing or that things are getting better,” she says.

Historically, researchers have associated the experience primarily with depression. However, a 2021 paper in the journal World Psychiatry pointed to an emerging consensus that linking the experience solely with depression may be misguided. The habit is related to many disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety disorders, eating disorders, substance abuse disorders, and insomnia.

Canter agrees that it’s a feature of many conditions. “While we most often see it as a symptom of depression or anxiety, it can be a symptom of PTSD and is often a part of insomnia,” says Canter.

How Can You Stop Rumination?

When you’re caught up in a cycle of negative thinking, it can seem almost impossible to get out, says Canter. But there are some proven techniques to break the cycle and stop what seems like an endless loop of doom thinking.

For example, if you’re about to give a presentation at work, you may find yourself on a spiral of negative thinking that goes something like this: “I’m going to blow this; I’ll lose my job; my professional reputation will be ruined; I’ll never get another job.” In that case, try replacing those thoughts with more positive ones: “I know this will be hard, but I’m prepared. I’m going to do the best I can, and it will be over soon. One way or another, this will not ruin my life.”

With rumination, there is a tendency to isolate yourself and dwell on negative thoughts, so Canter recommends an approach called behavioral activation. Often effective in treating depression, this simply means getting up and doing something.

“Just getting up and getting out of the house and doing the things that you need to do and things that you usually enjoy gives you a chance to think about something else,” Canter says.

Read More: The Spiral of Thinking About Thinking, or Metacognition

When Should You Seek Help for Rumination?

If these techniques don’t work for you, and you find that your negative thinking is interfering with your life and keeping you from doing the things you need and want to do, then it’s probably time to seek professional help.

There are several therapies, including cognitive behavioral therapy, that can help you manage your negative thoughts as well as address any related problems you may have.

If you or someone you know is in a mental health crisis, call or text the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988. The Lifeline provides 24-hour, confidential support to anyone in suicidal crisis or emotional distress.

Read More: Research Suggests How to Prevent Unwelcome Thoughts

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:

Avery Hurt is a freelance science journalist. In addition to writing for Discover, she writes regularly for a variety of outlets, both print and online, including National Geographic, Science News Explores, Medscape, and WebMD. She’s the author of “Bullet With Your Name on It: What You Will Probably Die From and What You Can Do About It,” Clerisy Press 2007, as well as several books for young readers. Avery got her start in journalism while attending university, writing for the school newspaper and editing the student non-fiction magazine. Though she writes about all areas of science, she is particularly interested in neuroscience, the science of consciousness, and AI–interests she developed while earning a degree in philosophy.

Discussion about this post