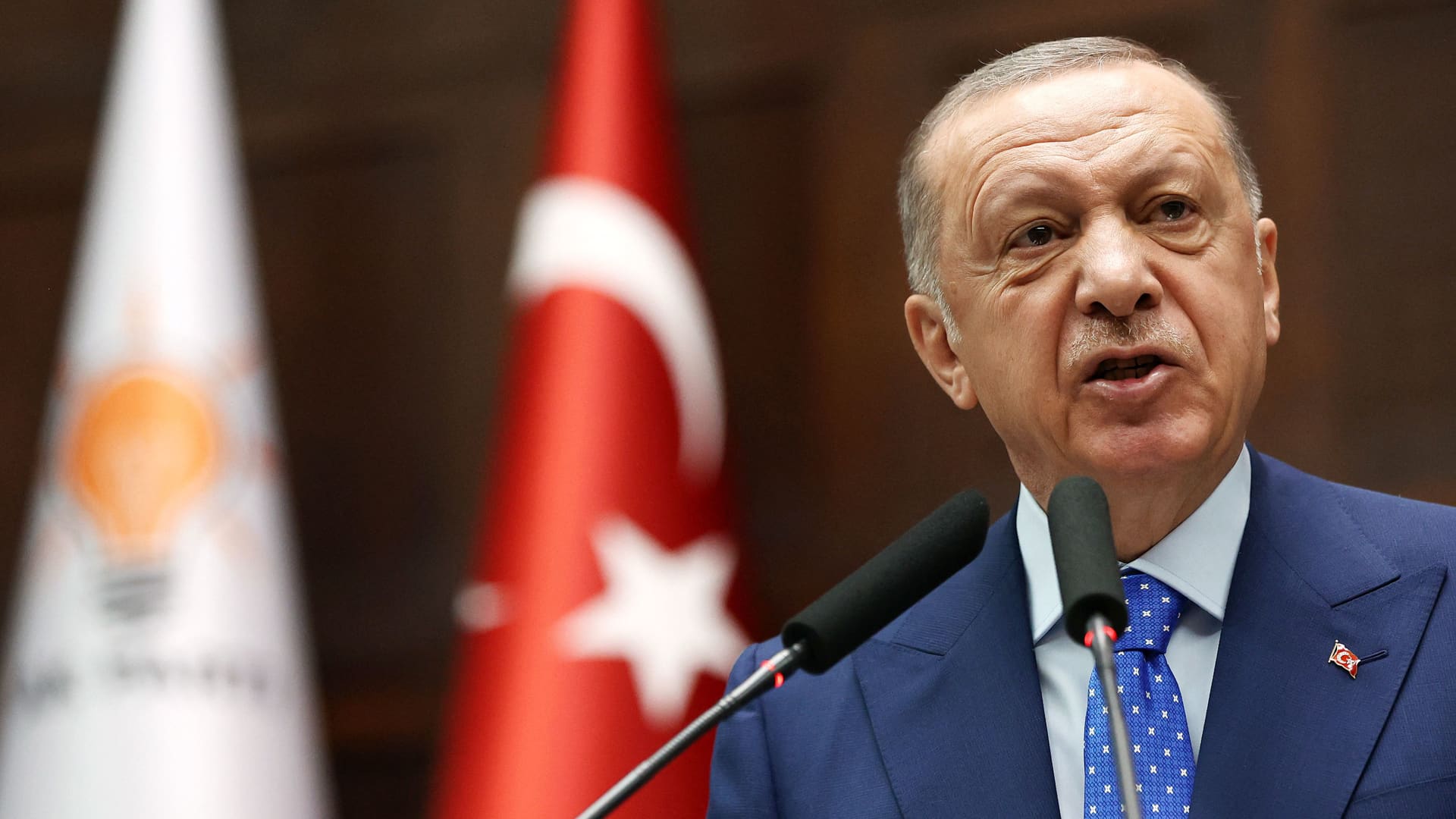

Turkey’s President and leader of the Justice and Development (AK) Party Recep Tayyip Erdogan delivers a speech during his partys group meeting at the Turkish Grand National Assembly (TGNA) in Ankara, on May 18, 2022.

Adem Altan | AFP | Getty Images

Turkish media reported on Sunday that Recep Tayyip Erdogan has won Turkey’s 2023 presidential election, extending his rule into its third decade in power after facing the tightest race of his career.

Turkish public broadcaster TRT has called the presidential election for incumbent Erdogan.

State news agency Anadolu’s vote count shows Erdogan leading opposition candidate Kemal Kılıcdaroglu 52.11% to 47.89% with 98.52% of the vote counted.

Official numbers have been slower than media counts, and while they show Erdogan leading, he has not officially been announced the winner.

Analysts saw the 69-year-old Erdogan’s victory as all but in the bag after the first vote on May 14, which saw him come out five percentage points ahead of his rival, in a giant blow to the opposition.

Kilicdaroglu and his party CHP had pledged change, economic improvement, the salvaging of democratic norms and closer ties with the West — something many expected to take them to victory, especially as years of Erdogan’s economic policies helped create a cost-of-living crisis in Turkey. But in the end, it wasn’t enough.

The AK Party leader’s popularity remains alive and well, even despite public anger at a slow government response following a series of devastating earthquakes in February that killed more than 50,000 people.

Many in Turkey — and the Muslim world more widely — see Erdogan as a protector of faithful Muslims who elevates Turkey globally and pushes back against the West, despite being a longtime Western ally.

By contrast Kilicdaroglu’s party, the CHP, strives for the fiercely secular model of leadership first established by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, founder of the modern Turkish state. It’s known for being historically more hostile to practicing Muslims, who form an enormous part of the Turkish electorate, although the CHP under Kilicdaroglu has softened its stance and was even joined by former Islamist party members.

Big decisions ahead

Erdogan has no shortage of work ahead of him — and his decisions will continue to have impacts far beyond Turkey’s borders. The country of 85 million people boasts NATO’s second-largest military, houses 50 American nuclear warheads, hosts 4 million refugees and has taken up a key role in Russia-Ukraine mediation. Western allies will also now be waiting to see whether Erdogan finally agrees to accept Sweden’s application to join NATO.

Erdogan served as Turkey’s prime minister from 2003 to 2014 and president from 2014 onward. He came to prominence as mayor of Istanbul in the 1990s, and was celebrated in the first decade of the new millennium for transforming Turkey’s economy into an emerging market powerhouse.

Recent years, however, have been far less rosy for the religiously conservative leader, whose own economic policies have contributed to inflation surpassing 80% in 2022 and Turkey’s currency, the lira, losing some 77% of its value against the dollar over the last five years.

International and domestic voices alike also sound the alarm that Turkey’s democracy under Erdogan is looking less democratic by the day.

The frequent arrests of journalists, forced closures of many independent media outlets and heavy crackdowns on past protest movements — as well as a 2017 constitutional referendum that vastly expanded Erdogan’s presidential powers — signal what many say is a slide toward autocracy.

The Turkish president rejects the criticisms. But with a fresh mandate to lead and previous reforms consolidating presidential power, very little stands in the way of a stronger Erdogan than ever before.

Discussion about this post