Few hurricane seasons in recent memory have arrived with as much anticipation as this year’s, and for good reason: few seasons have ever been favored for the sort of ample activity that current outlooks call for over the next seven months.

On a recent webinar together with the National Weather Service in Raleigh, we broke down the forecasts for this year and shared tips for storm readiness. This blog post includes a summary of that briefing, with what you need to know about the upcoming hurricane season. A link to the recording of the webinar will be added to this post as soon as it is available.

Tropical Climatology

The North Atlantic Ocean is favorable for tropical storm development because of the warm ocean currents — including the Gulf Stream — that provide a warm sea surface from which storms can extract energy, and because of generally light upper-level winds blowing across the tropical development region that mostly prevent developing storms from being torn apart.

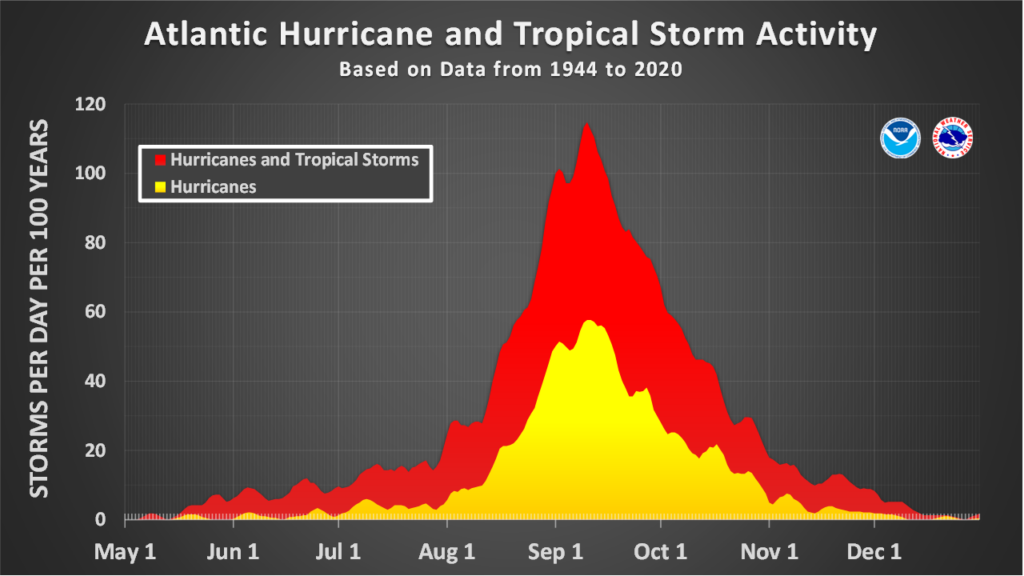

As the Atlantic warms up during the summer months, the first storms typically begin developing in June, often over the relative hot spots in the Gulf of Mexico or the Gulf Stream, which parallels the Southeast coastline from Florida through Cape Hatteras. Some storms even sneak in before the official start of hurricane season on June 1, as short-lived Bertha did on May 27, 2020.

Activity ramps up in August and September, with long-lived storms forming just off the coast of Africa and tracking westward. While their exact trajectories are determined by atmospheric wind and weather patterns, storms taking a particular path north of the Caribbean and through or near the Bahamas may eventually reach North Carolina, like Floyd, Dorian, and a number of other storms have done.

As with our air temperatures each fall, ocean temperatures begin cooling off by October and November, so tropical activity tends to wind down then as well. Late in the season, the central Atlantic, Caribbean, and southern stretches of the Gulf Stream are the most likely areas for storm development. That was the case in October 2015, as Hurricane Matthew slammed the Bahamas at Category-4 strength before drifting northward as a weaker, albeit wetter, storm just off our coast.

On average from 1991 to 2020, the tropical Atlantic had 14 named storms, 7 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes form per year. But several recent seasons have been much more active than that, supercharged by warm water across the Atlantic.

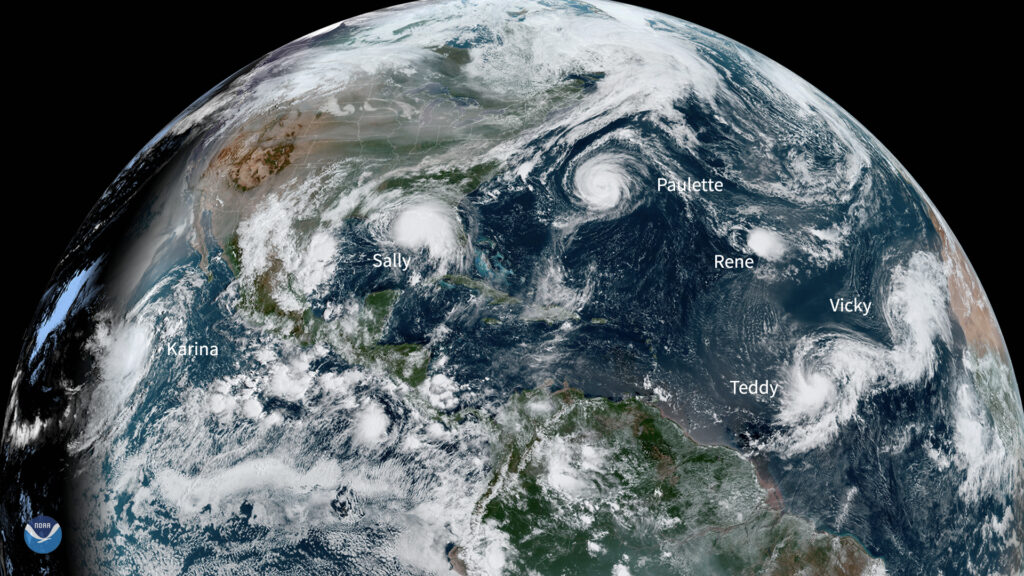

There were a record-setting 30 named storms in 2020, along with 21 tropical storms in 2021 and 20 in 2023. The same ingredients that supported so much activity in those years are converging again in 2024.

This Season’s Outlook

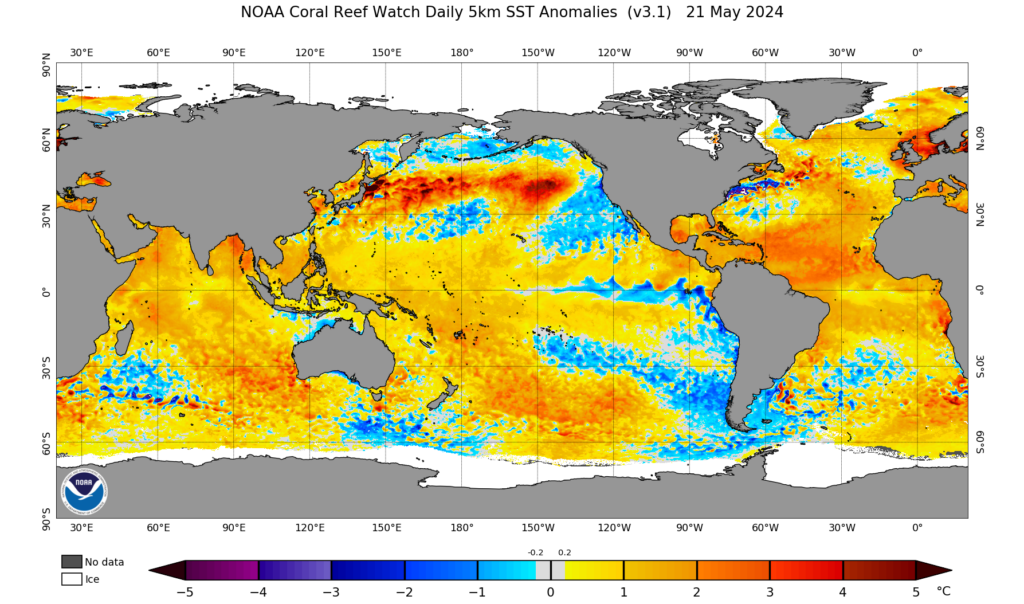

The first indications of an active Atlantic began emerging over the winter, when the ocean seemingly missed the memo about what time of year it was. Sea surface temperatures across the tropical Atlantic barely dropped below 26°C, or 79°F – a level not typically reached until June.

Through mid-May, the basin remains at record warm levels for this time of year. The main development region was as warm on May 15 as it usually is on August 1, and on May 19, the Caribbean Sea had sea surface temperatures of almost 85°F: warmer than that region’s average temperatures reach at any point in the season.

On the other side of the world, it’s a different story, as cooler water is beginning to bubble up in the equatorial Pacific Ocean – a sign of a likely La Niña event emerging. If we do indeed see the return of La Niña for the fourth time in five years, it should slacken the upper-level winds blowing across the Atlantic, further reducing the wind shear and encouraging storm formation.

For forecasters, that has led to one key conclusion: it’s likely to be a busy season in the Atlantic. NOAA’s official outlook, released yesterday, predicts an 85% chance of above-normal activity, with a forecast of 17 to 25 named storms, 8 to 13 hurricanes, and 4 to 7 major hurricanes.

In their April outlook, the forecast team at Colorado State University called for 23 tropical storms and 11 hurricanes, the latter being the most ever predicted since their pre-season outlooks began in 1995.

NC State’s own forecast team similarly predicts 10 to 12 hurricanes, along with a more moderate but still-active 15 to 20 named storms this season. Their forecast, which is based on historical data from past seasons with similar environmental conditions, also expects increased activity in the Gulf of Mexico. That could mean more remnant storms reaching western North Carolina, as we saw in 2020.

Numbers and Names to Note

If this season will indeed be one of the most active ever recorded, then there are a few milestones to watch for in the months ahead. First, past active seasons have gotten off to a fast start. Both 2021 and 2023 had a record-tying three named storms in June, while 2005 and 2020 each had five named storms in July.

We could also have our 14th named storm – equaling the 30-year average annual total for the Atlantic – before the mid-September peak of the season. In 2020, we hit that mark when Tropical Storm Nana formed on September 1, while in 2005, the fourteenth storm, Nate, developed on September 5.

If the oceans reach their warmest levels in September, as is often the case, then it could be a blockbuster month, perhaps rivaling the ten named storms that formed in September 2020. The remnants from two of those systems, Sally and Beta, moved in from the Gulf of Mexico and soaked parts of North Carolina.

And if the Atlantic remains warm and the La Niña takes effect, then the end of the season could be active as well, perhaps on par with the three November named storms in 2020, including Eta, which fed moisture ahead of a cold front to inundate North Carolina that fall.

We have twice exhausted the standard list of 21 storm names for the basin, with the next storm – in both cases so far named Alpha – forming on October 22 in 2005 and September 17 in 2020.

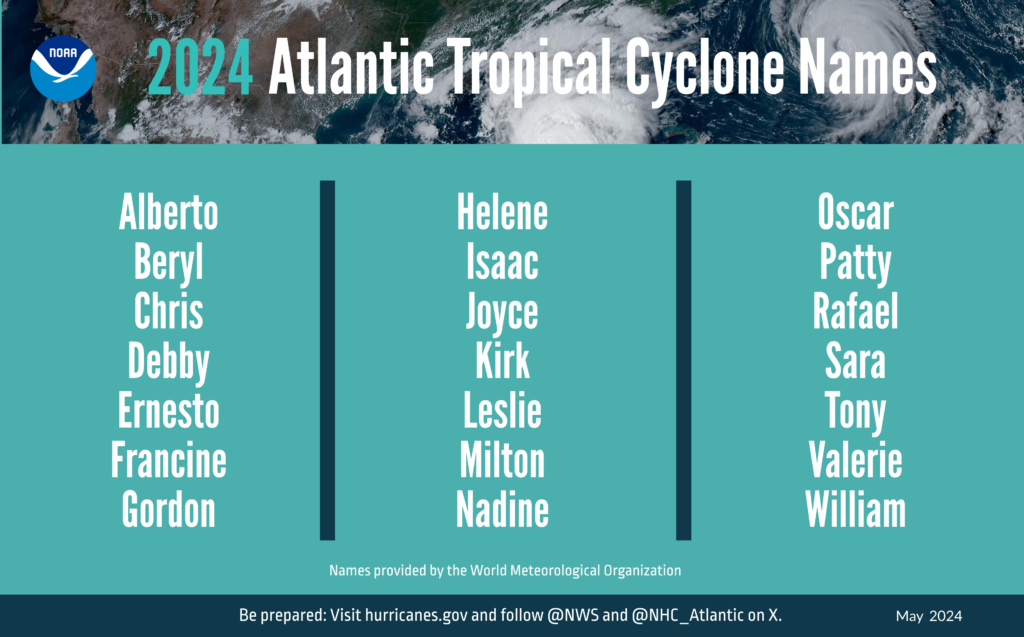

If we see similar activity in 2024, one thing’s for sure: there won’t be another Tropical Storm Alpha or any other Greek-lettered names this year. That’s because a procedural change by the World Meteorological Organization following the busy and destructive season in 2020 replaced the Greek alphabet with a supplemental list of more standard names, which won’t change from year to year unless a storm’s impact warrants its retirement.

Among the initial list of 21 names this year, there are a few familiar ones, including Alberto – a previous iteration of which circled off the Carolina coastline in May 2012 – and Ernesto, whose 2006 incarnation caused heavy rain and flooding in the Wilmington area.

A new name on this year’s list is Francine, which replaced Florence after it was retired following the 2018 season. With a history of destructive F-named storms in North Carolina, including the phonetically similar Fran and Frances, the memories of those storms will surely return if Francine faces down North Carolina this year.

Preparing for Potential Impacts

Our state has seen its share of storms move through in recent years, including tropical storms Idalia and Ophelia last year, which each caused heavy rain and coastal flooding in areas such as Whiteville, New Bern, and Washington. The previous year saw more widespread winds and rain from the remnants of Hurricane Ian.

But we’re now going on four years since the last landfalling hurricane in North Carolina – Isaias in 2020 – so with an active season in the offing, this is a good time for a refresher about storm readiness.

NOAA’s Hurricane Preparedness guide offers a collection of resources and links worth reviewing. Pre-season preparations should include building a disaster supply kit, making a plan with your family – and for your pets – in the event of a disaster, and securing your home to reduce the risk of damage.

As part of preparing for potential hazards from tropical storms, it’s a good idea to know whether your home or community is in a flood risk zone. Coastal residents can explore more with NOAA’s Coastal Flood Exposure Mapper tool, while the North Carolina Department of Public Safety provides evacuation zones for coastal counties.

If you’re vacationing at the coast this summer, be aware that even distant hurricanes can create deadly rip currents. Before you wade into the water, be sure to check the National Weather Service’s Experimental Beach Forecast page to find your local rip current risk and any other hazards affecting your stretch of sand and surf.

And as North Carolina has learned the hard way over the years, hurricane hazards don’t stop at the shoreline. Gusty winds and flooding can affect areas well inland, too. To better communicate this risk, the National Hurricane Center is adding inland watches and warnings to its standard forecast cone graphic during this hurricane season.

Given the active outlook, North Carolina could be in the crosshairs at some point in the season, whether it’s from winds, rain, storm surge, high surf, or all of the above. Preparing now and knowing how to stay alert if and when storms strike will help us all better weather the potential stormy summer ahead.

Discussion about this post