“My father used to get angry,” Van Leo, an Armenian-Egyptian photographer, once shared in a 1998 interview. “He’d tell me: ‘Did you make the studio for yourself or the customer? Stop making photos of yourself!’”

Van Leo, who worked from the 1940s until the 1970s in Egypt, was more than just a photographer; his lens did not merely record the surface, the world we see everyday. He was more interested in capturing the soul – the raw, unspoken emotions beneath. Each photograph was an attempt to express an emotion, or a facial expression that uncovers the hidden aspects of ourselves we often keep veiled.

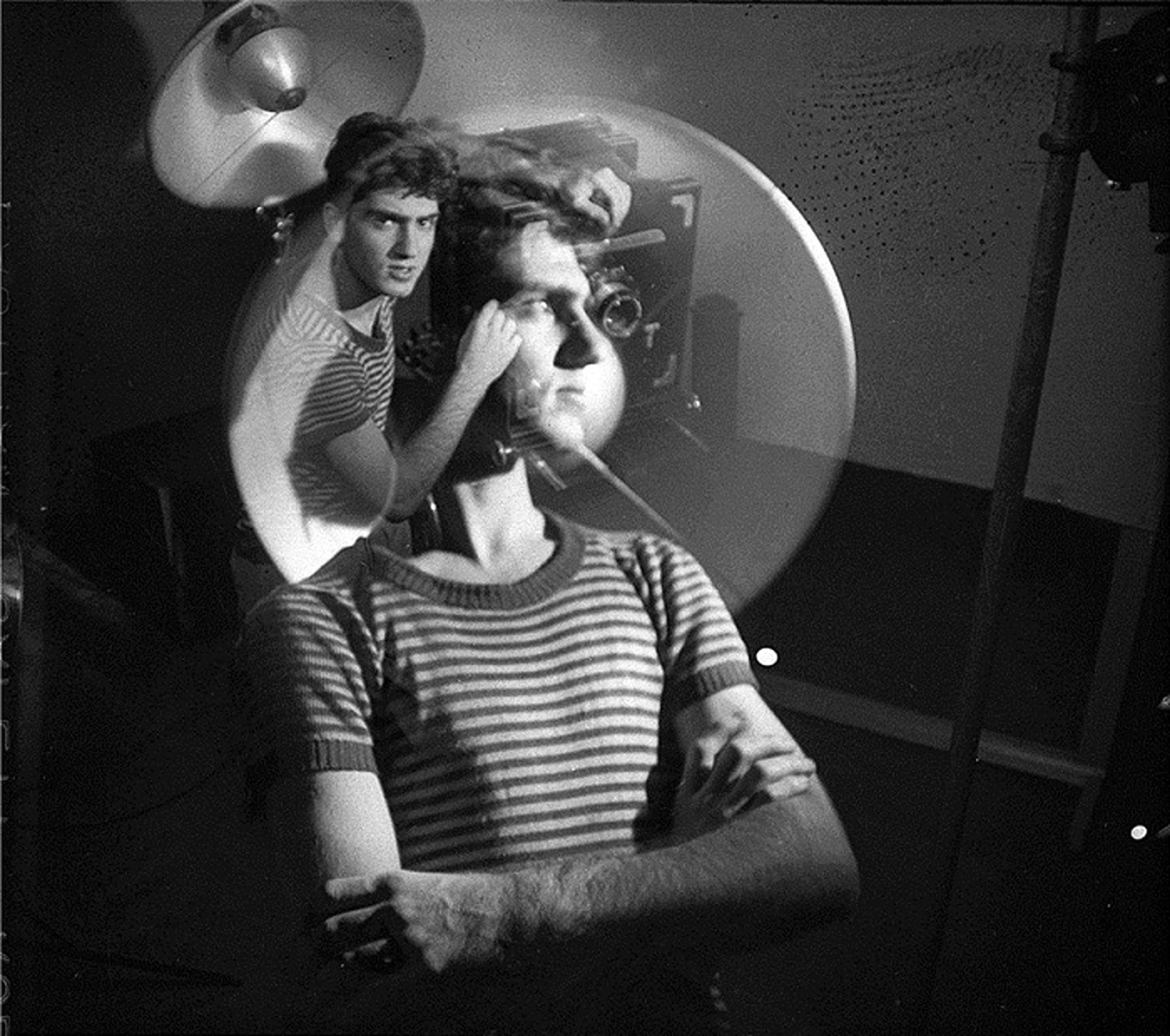

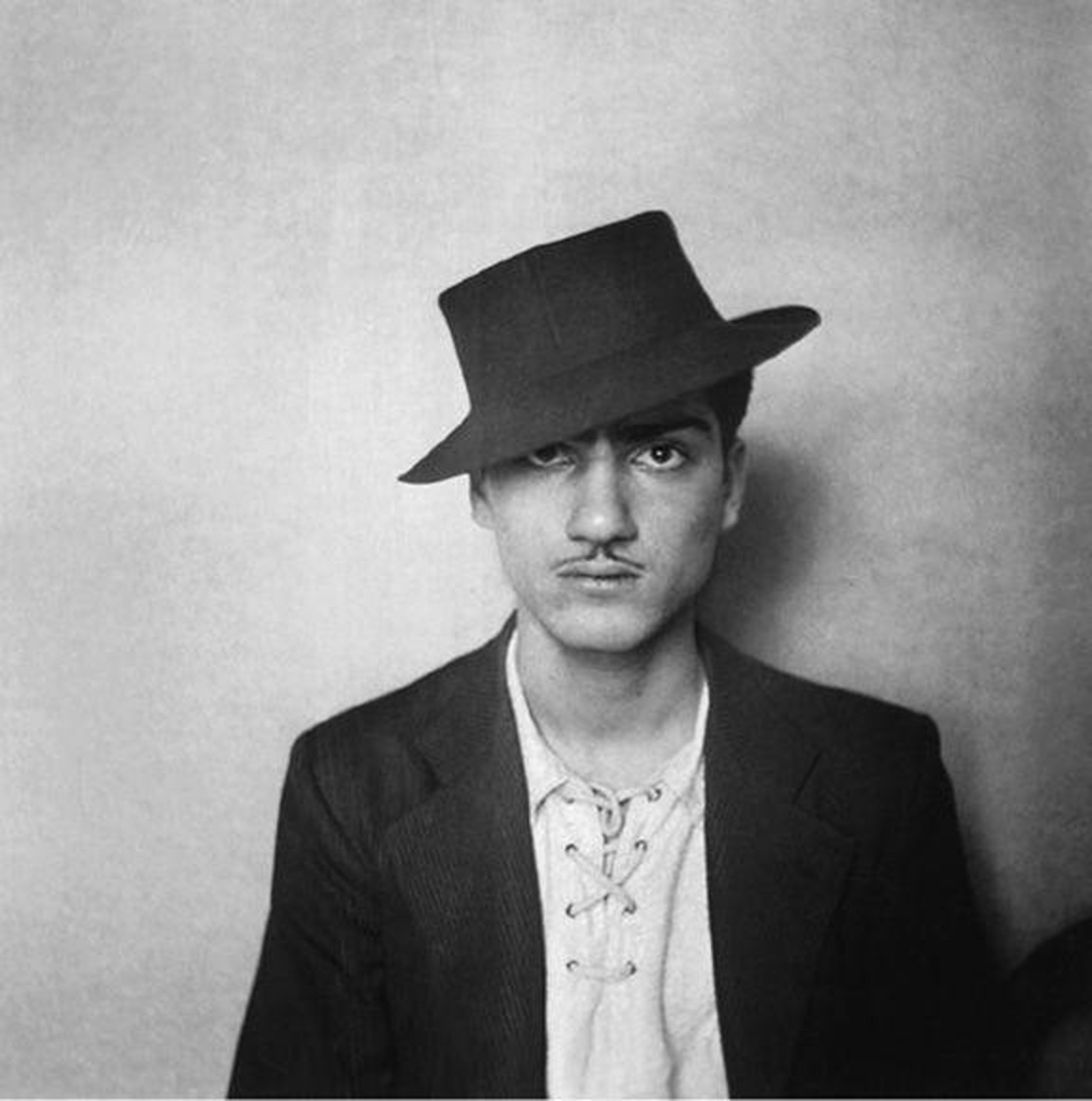

He was known to occasionally close his studio for extended periods to capture himself in various costumes, a practice akin to performance art. From embodying a pilot, to a robber, a Bedouin, a cowboy, the Wolfman, and numerous other characters, his studio was like a theatrical stage for self-exploration.

“In my studio, I feel free to do anything with myself,” he once said. “My self-portraits are very unconventional, from the lighting to the facial expressions. I did around 300 to 500 self-portraits in total.”

For him, it was not just a profession; it was the very air he breathed, a lifelong performance where he can freely express and connect with his artistry.

Glamour and surrealism

Born Levon Boyodjian in 1921 in Turkey, he chose Van Leo as his stage name, paying homage to the artist Van Gogh and also symbolizing his transformation into his artistic persona.

Escaping the horrors of the Armenian Genocide under the Ottoman Empire, his family found refuge in Cairo. Growing up, the allure of Hollywood postcards initially drew him to photography, inspiring him to recreate that kind of glamour in Egypt.

Over time, his photographic style drew lifeblood from the theatricality of Hollywood postcards. From the expressive hand gestures to the dramatic gazes, these postcards became the foundation of his artistic approach.

More than just lighting or camera angles, he saw these images as theatrical performances frozen in time, each exuding glamour and artistry.

“Face expressions are the most important for me, other than the lighting or the camera angle. Before I take any photograph, I always study the face and the facial expression,” he said.

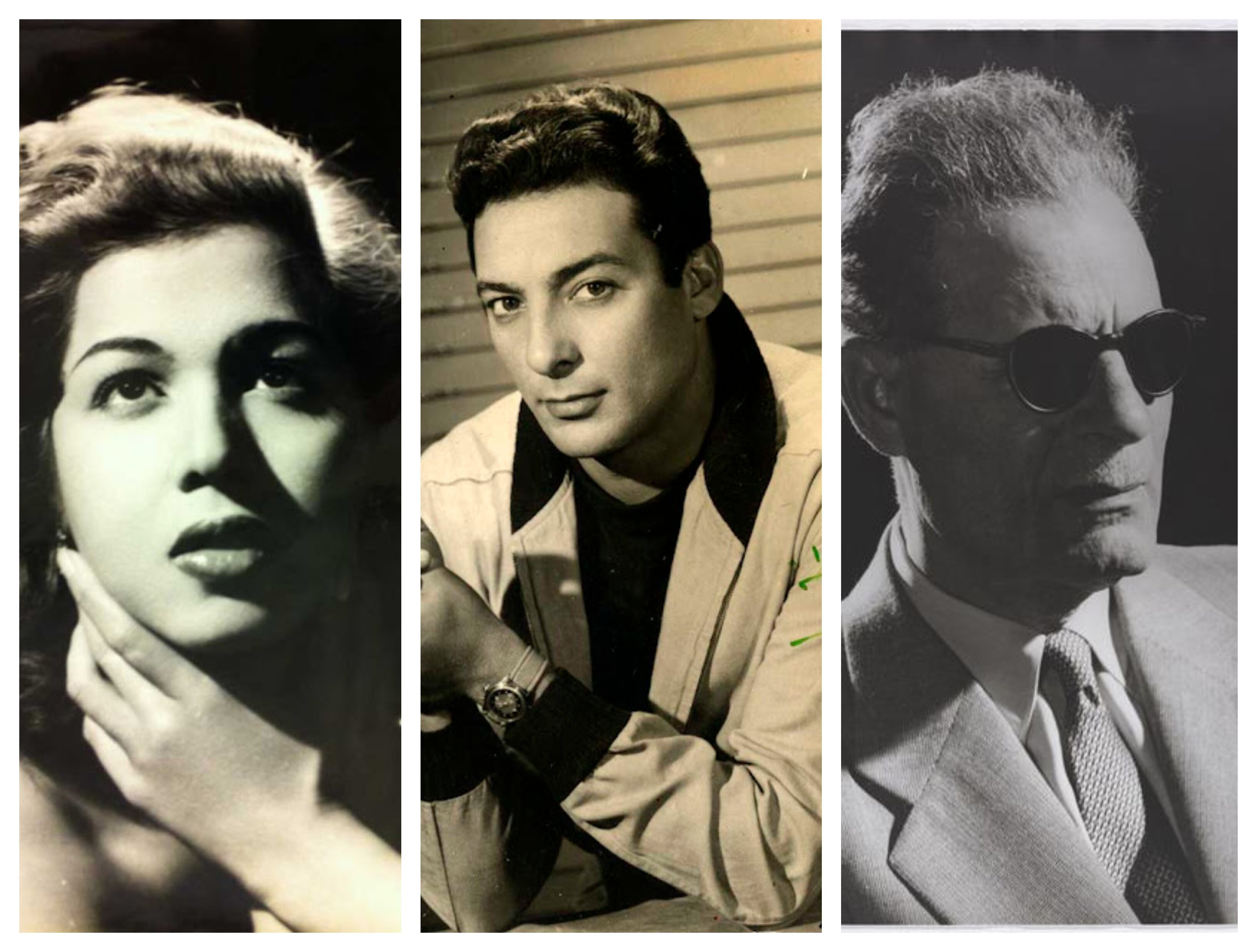

His affinity for capturing emotion and expressions naturally drew him to entertainers and creatives, since they are more adept at expressing a range of feelings. From the 1950s through the 1960s, Leo’s studio became a star-making hub.

Actors, both established and aspiring, always turned to his studio to create a true artistic and glamorous self-portrait. Egyptian cinema legends like Rushdy Abaza, Farid al-Atrash, Faten Hamama, Sherihan, and the international icon Omar Sharif were among his clients.

One of Leo’s early clients was Rushdy Abaza, then an aspiring actor working a day job at Union-Vie French insurance, which was located in the same building as Leo’s studio. Abaza, needing a portfolio to impress directors, sought out Leo’s talent.

The final portrait Leo created became Abaza’s ticket to his first film roles. As Abaza’s fame grew, he recommended Leo’s work, solidifying the photographer’s status as a favorite among Egyptian cinema’s elite.

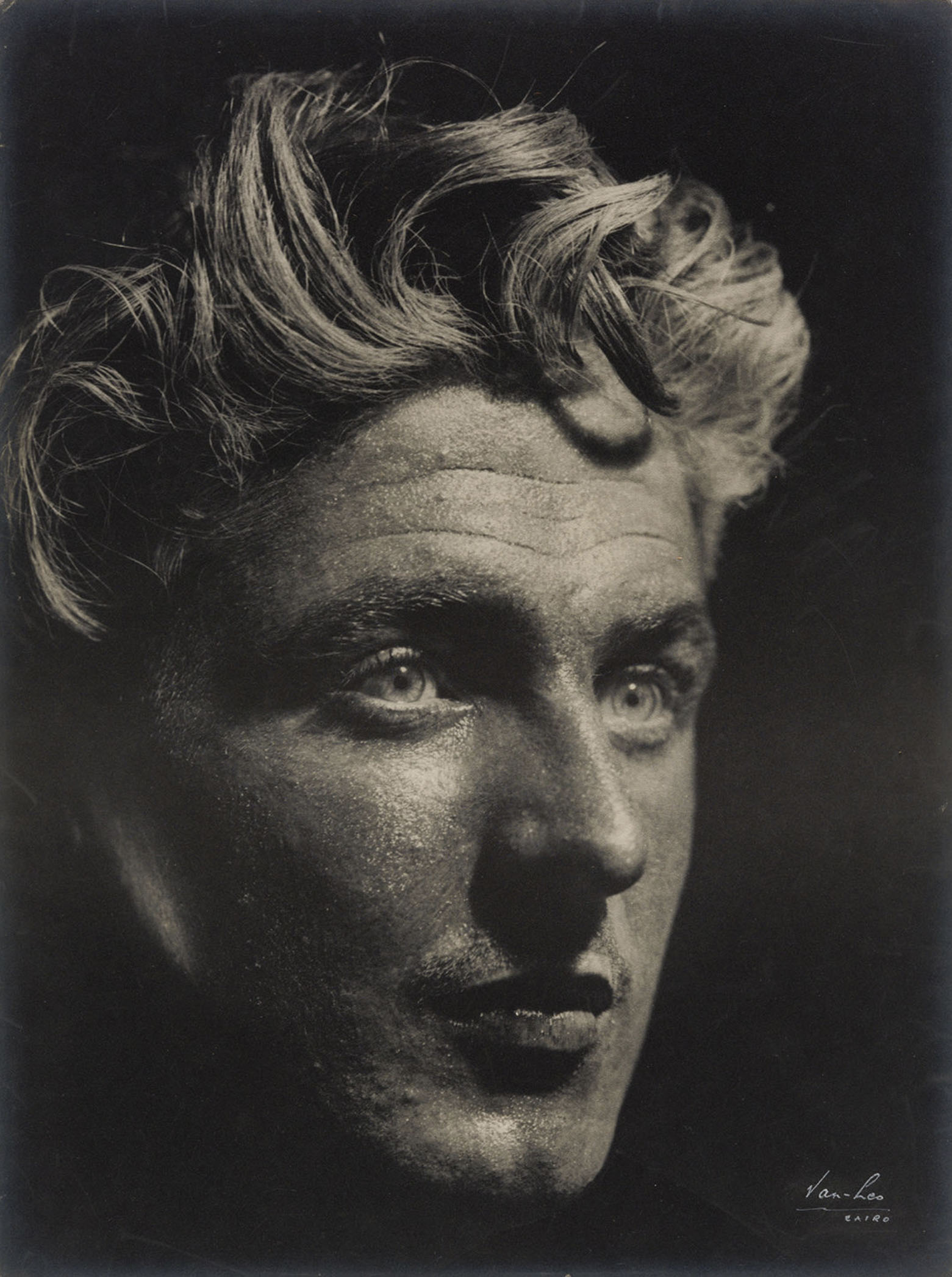

Famously known for imbuing every photograph with his own artistic fingerprint, he always transformed them into evocative and enigmatic works of art that transcended reality. As writer and scholar of the Arab world Raphael Cormack once highlighted, “he sat on the edges of Surrealism, without ever really being a Surrealist.”

One of his most iconic photographs is his 1944 portrait of South African entertainer Teddy Lane. Recognizing Lane’s striking features, Leo applied a sheen of Vaseline on his face, and then placed a black velvet backdrop to draw the eye solely to the entertainer’s face.

This photograph alone embodied Leo’s philosophy, as he once said, “You must make some pictures for yourself, from your inspiration, not just what the client wants.”

Intuition and a keen eye for emotion were also the hallmarks of Leo’s artistic approach, which is best exemplified by his portrait of Taha Hussein, one of Egypt’s most revered blind writers.

“The inspiration was from my heart. I saw the dark eyeglasses, and I already understood that he was a famous personality. I started to play with the lights, and it came out like this one,” he said.

This portrait of Hussein continues to stand the test of time and remain ingrained in the memory of Egyptians. His approach is proof that photography is not just about producing a pleasing aesthetic; it is about creating an experience that breathes life into the image.

Final days

It is no surprise, then, that even to this day, Leo’s photographs defy time. Through his lens, the spirit of the 40s, 60s, and 70s continues to breathe, offering a glimpse into a time we can’t fully recapture.

His artistry flourished in an age before color photography and technology, and when artists had to experiment and use the full capacity of their imagination due to the limited resources that they had. With no stylists, photo editors or art directors, Leo relied solely on his own vision and intuition.

The best way to describe it is that the camera was like an extension of his heart, and of the environment that nurtured his artistic spirit.

The Egypt of Leo’s youth, a cosmopolitan hub, began to fade with each passing year. A rising tide of conservatism in the 1970s replaced the world he once knew, which left him feeling less inspired to continue taking photographs.

Photography increasingly became more commercial rather than an artistic pursuit, with family and wedding portraits dominating his client list. He increasingly felt disconnected from his creative vision amidst the commercial demands, longing for a return to a time when artistic expression was at its peak.

In one moment of despair, fearing his photographs could be used against him, he destroyed a vast collection that might have revealed more of his artistic legacy. Marking the end of his career in 1998, he donated 13,000 photographs, 16,000 negatives, and numerous documents to the Special Collections Library at the American University in Cairo.

Even years after his death in 2002, his work continues to breathe. In 2023, the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles debuted ‘Becoming Van Leo,’ the first international retrospective of the photographer’s career.

The only record of his voice in the digital age is a conversation with Fouad Elkoury and Akram Zaatari, co-founders of the Arab Image Foundation. Conducted in 1998 as part of their research for a comprehensive three-volume collection titled ‘Becoming Van Leo‘ (2022), this interview showcases Leo’s life story and artistic process.

“The art of photography is over,” he said at one point in the interview. “People now use photography for their ID pictures.”

Discussion about this post