Now is the best time in the history of the U.S. to cast a vote. Yes, American elections have flaws. They’re marred by voter disenfranchisement, gerrymandering, the inherent weirdness of the electoral college and recent cases of ballot box arson. But the act of voting itself has been unfairly tarnished, most notably by former president Donald Trump’s “Big Lie” that the 2020 election was fraudulent. That claim is especially preposterous because modern voting procedures are only becoming more robust—and those casting ballots by mail or machine in this year’s presidential election can, in fact, be more confident than ever that their votes will be tallied accurately.

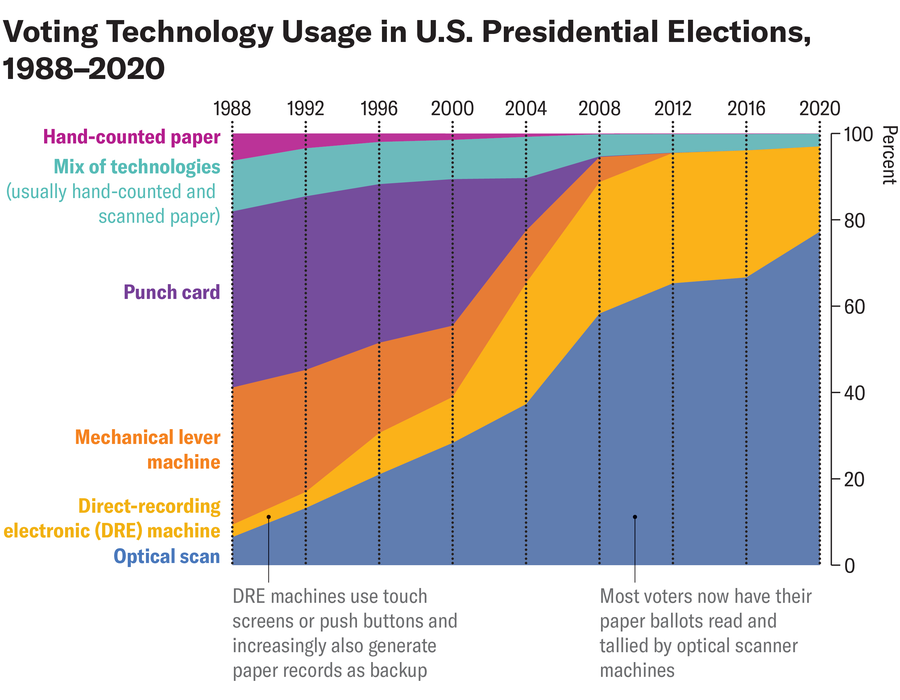

One reason for that confidence is the adoption of voting technology that combines machine efficiency with the verifiability of a paper trail. This is the result of a shift that began two decades ago, after system jams and punch-card fragments—Florida’s infamous “hanging chads”—led to a fiasco that left the 2000 election results unclear for five weeks. Congress’s response, the 2002 Help America Vote Act, phased out the use of punch-card ballots and lever machines in federal elections. Most Americans now vote with optical scanners, which process marked selections on paper sheets. In the 2020 presidential election, Georgia’s polling sites used hand-fed optical scanners; an audit of the nearly five million votes cast in the state, the largest hand count of ballots in recent U.S. history, confirmed that President Joe Biden won. County error rates were 0.73 percent or less, and most had no change in their tallies at all.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Although U.S. voting machines are not totally tamperproof—no machine is invulnerable—as precaution against remote hacking, the vast majority do not connect to the Internet (potentially problematic exceptions aside). In a recent election security update, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, or ODNI, said the intelligence community does not have evidence of adversaries attempting to compromise the U.S.’s physical election infrastructure. Interfering in a meaningful way with the country’s diverse, decentralized systems would be essentially impossible, the ODNI update noted. Instead foreign actors prefer the easier route of psychological influence, trying to sway voters or undermine election confidence through propaganda and disinformation.

“For a host of reasons, the potential vulnerability of individual voting machines doesn’t translate into systemic vulnerability,” says political scientist Mark Lindeman, policy and strategy director at Verified Voting, a nonprofit group that tracks election systems across the country. “Hackers don’t get to go one-on-one with voting machines. There’s a whole set of procedural safeguards to protect them.” Physical ballots add trustworthiness to the system, too, because they are verifiable, auditable and recountable. Scientific American spoke with Lindeman about why Americans, despite experiencing so much voting agita, in fact live in a golden age for casting ballots.

[An edited transcript of the interview follows.]

Verified Voting estimates that nearly 98.6 percent of registered voters live in jurisdictions where votes have a paper trail of some form. Why is that important?

It’s twofold. A paper trail provides a fail-safe. If something does go wrong with the systems—and what we’ve seen in certain elections is machines miscounting votes, never because of hacking, always because of an error in how they were configured—the paper ballots have been available to correct those mistakes.

Perhaps an even greater value of paper ballots that voters have verified, and that election officials use in audits and recounts, is to provide assurance. Instead of arguing about whether the machines counted votes accurately, we can look at the paper ballot evidence and find out. We can move away from abstract speculation about technology into observable reality.

Voting machines in the U.S. generally aren’t connected to the Internet. In fact, Verified Voting has opposed proposals for Internet voting. Why is that?

We’re all about paper ballots that voters can verify and that election officials then can use to verify the counts. We see electronic ballot transmission, Internet voting of any form, as a step away from what has made elections in recent years more secure than they were 20 years ago, when Verified Voting was founded. The country is just now getting to the point where practically everyone votes on paper ballots that they can verify. Internet voting is the antithesis of that.

If anyone claims that an Internet election (or an election where a lot of votes have been electronically transmitted) has been hacked, I don’t know how anyone can convince people otherwise.

If you’re voting in this election, how confident are you that your ballot will be counted?

I voted early here in the state of New York using a hand-marked paper ballot and a scanner. New York State has a 3 percent audit, and I’m very confident that my vote will be counted accurately.

What’s a 3 percent audit?

New York randomly selects 3 percent of the scanners that are used in the election and hand counts those ballots to make sure they were counted accurately. Most states conduct some kind of postelection audit. The details vary, but to have a percentage-based audit of some form, as New York does, is the most common model.

Was there ever a voting heyday prior to this? (A recent Pew Research Center survey of registered U.S. voters found that about one in four believe the presidential election will be run at least somewhat poorly.)

I don’t think there’s ever been a better time to vote in the U.S. There was also a time when everyone voted on paper ballots—but election administration, frankly, was riddled with corruption. No one is really calling to go back to the days of Tammany Hall [laughs].

It’s not necessarily that paper ballots by themselves are inherently secure. Paper is fragile. But the checks and balances that have been put into place around paper ballots have never functioned more effectively in the U.S. than they do now. Election administration is far more professionalized than it was even 20 years ago. Election officials are better trained. They’re more aware. It feels kind of strange to talk about this as a golden age of elections amid all the anxiety, but I don’t see any other way to interpret the facts.

What can we do to restore confidence in American voting?

[Lets out a weary sigh.]

I felt that in my bones.

I’m a child of the Enlightenment. I think that reflecting on reality is the place to start. Some of that reality is the basic technology in place: the fact that our votes are recorded on paper ballots; procedurally, the fact that those paper ballots are protected—that in most states, they’re used in audits to verify the counts.

Beyond that, a large majority of Americans actually do trust their local election officials. In my experience, that trust is well placed. The election officials I’ve worked with around the country are very focused on the mission of making elections work for their voters. So I don’t really know what it takes to convince people to appreciate the good around them instead of fear spiraling or morbid speculation about terrible things that might be happening. That might be above my pay grade.

If you could improve one thing about the mechanics of American voting, what would that be?

We can do better on truly accessible voting than we’re doing now. I think that accessibility has been grafted onto most of the voting systems on the market. If we focus more on accessibility from the ground up, we can do better for a wider range of voters.

Can you give me an example of accessible voting?

Many states provide some kind of touch screen interface that also can be equipped with [“rocker pedals,” large buttons that can be operated with feet, hands or other body parts], and with what are called sip-and-puff interfaces [devices that are operated by breathing]. These all provide ways for voters with various abilities and disabilities to interact with a voting machine. They can adjust the contrast; they can adjust the font size. And with audio interfaces, if you can’t see the ballot, you can have the ballot read to you.

These are all interfaces that provide a greater range of voters with the ability to mark and cast their ballots independently. And they’re a great improvement over nothing. But also, I think that voters with disabilities, in many cases, can testify that those interfaces don’t work as well in practice as they are built to do in theory.

We’re in the early days of accessibility, and I would like us to level up.

Discussion about this post