A steady stream of early-fall-like days made for a warm November, and despite returning rainfall, it was a dry month too. November wrapped up a fall defined by big rain events and background warmth.

The Warmth Winds On

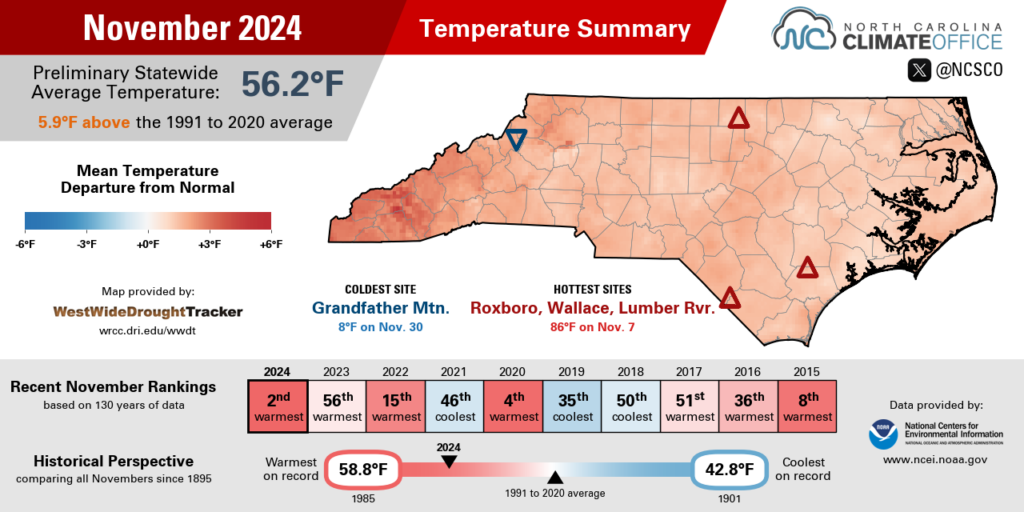

With temperatures more typical of September during stretches last month, November was overwhelmingly warm across North Carolina. Based on preliminary data from the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), our average monthly temperature was 56.2°F, which was our 2nd-warmest November since 1895, behind only November 1985 in the statewide rankings.

Locally, it was one of the top five warmest Novembers on record at a number of long-term weather stations. In Asheville, Elizabeth City, Lumberton, and Raleigh, it was 3rd-warmest November on record. Hickory set its 4th-warmest November. And Charlotte and Greenville recorded their 5th-warmest November locally.

That warmth was apparent with 80-degree temperatures to start the month as the state sat under high pressure. On November 6, Raleigh set a new daily record high of 84°F and Fayetteville tied its record of 85°F.

The following day on November 7, the mercury climbed as high as 86°F in Wallace, which was its latest day that warm since that station began reporting in 2000. Even in the Great Smoky Mountains, Oconaluftee recorded its latest 80-degree day on record on November 9.

Along with those unseasonable afternoons, the other sign of the prevailing warmth last month was the ongoing delay in the first fall freeze for much of the state. In central North Carolina, sites that typically see their first freeze in late October or early November had to wait until the week of Thanksgiving for that first chilly night of the season.

When a Canadian air mass dipped southward on November 22, low temperatures across the Piedmont finally dropped below freezing, but it was still the 3rd-latest first freeze on record for both Greensboro and Hickory.

As we previewed in our October climate summary, several northwest Piedmont sites did record their latest first freeze on record. In Yadkinville, the first freeze on November 17 was 26 days later than average, and Danbury’s first freeze on November 22 was 33 days later than average. It took until November 27 before the observing station at W. Kerr Scott Reservoir fell below freezing, a full 34 days later than its average first freeze date.

Charlotte and Raleigh didn’t feel their first freeze until November 29. In Raleigh, that was its latest first freeze date at the current airport location and the 2nd-latest on record locally, behind only a December 3 freeze in 1931. Coupled with Raleigh’s early final freeze last winter on February 21, that made for a 281 day freeze-free season in the capital, which was the longest on record there.

That late-month cooldown behind another Arctic cold front saw temperatures drop into the 20s as far east as Columbia and Elizabeth City. That chill was a far cry from how we started the month, but it wasn’t enough to offset the overall warmth in the final monthly ranking.

Precipitation Picks Up

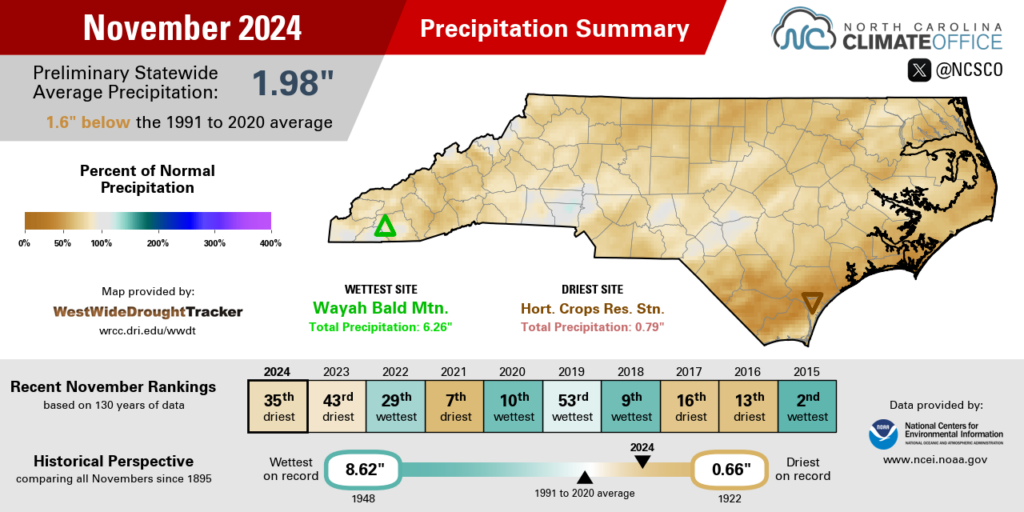

Rainfall returned in November following a dry October, but it was still an overall dry month across the state. According to NCEI, the preliminary statewide average precipitation of 1.98 inches ranks as the 35th-driest November out of the past 130 years.

After less than half an inch of rain fell across most of the state in October, November offered more substantive totals of 1 to 3 inches, although the bulk of that rain occurred in just one or two events.

The northern Mountains and Foothills were the first areas to receive some rainfall relief, with two-day totals of up to 1.30 inches in Sparta and 0.91 inches in Taylorsville on November 5 and 6. That was the first event at both sites with more than a quarter-inch of rain since Hurricane Helene in late September.

A more widespread soaking rain – and the most significant event of the month in most areas – happened on November 14 as a low pressure system crossed the state. For the only time all month, daily totals topped an inch at sites including Greensboro (1.52”), Raleigh (1.36”), and Greenville (1.14”).

Later, parts of the southern Mountains had up to 2 inches of rain on November 20, while Thanksgiving morning saw rain showers that also totaled more than half an inch in the west.

Despite improving on our October rainfall totals, a still-dry November meant expanding drought on either end of the state. Moderate Drought (D1) is now present throughout the Coastal Plain, which had monthly totals as low as 1.17 inches in Elizabeth City in its 11th-driest November on record.

Areas in the far southwest also saw drought emerge as local streamflow levels began to decline nearly two months after their surge from Helene. The late-month rain chipped away at some of that drought, but it was still a slightly drier-than-normal month for sites including Cullowhee and Franklin.

In the northern Mountains, the big precipitation story late in the month was the first snow of the season. On November 22, Beech Mountain was blanketed by 9 inches of snow, with 4.5 inches on nearby Grandfather Mountain and 3 inches in Boone.

That made for a rare scene in North Carolina: a snow-dusted football field on a game day as Appalachian State prepared to take on James Madison in its final home game of the year.

A Final Look at Fall

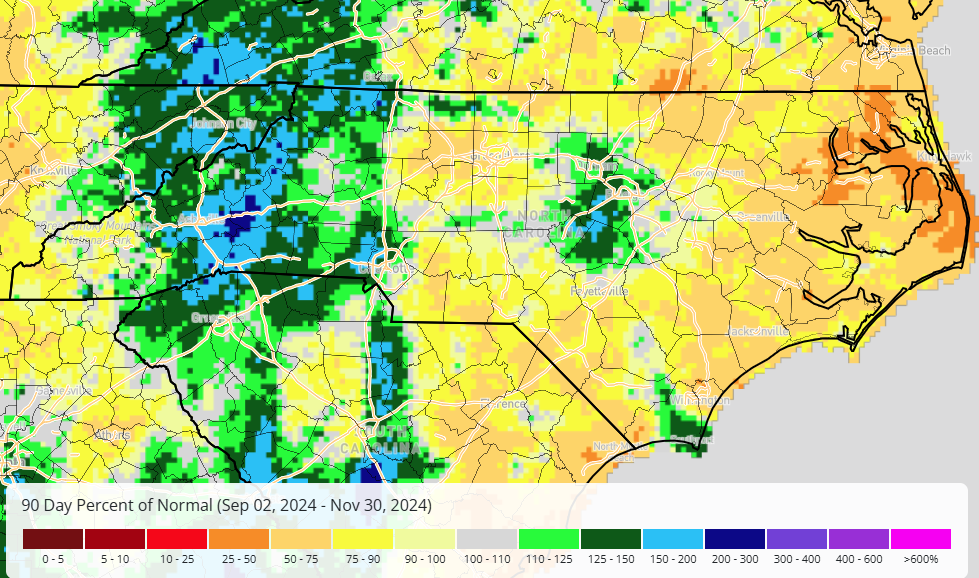

Last month, we noted the unusual start to the fall, with extreme wet conditions in September and extreme dryness in October. Instead of precipitation extremes, November brought overall warm temperatures, and the statistics from the entire season — both statewide and locally — reflect some of those standout conditions.

For the state as a whole, NCEI’s preliminary statistics show it was the 8th-warmest and 52nd-wettest fall on record. That wetter-than-normal precipitation ranking was driven heavily by our September storms, including Potential Tropical Cyclone Eight at the coast and Helene in the Mountains.

Asheville had its wettest fall on record with 20.02 inches, surpassing the 19.84 inches from 2004 that also featured a soaking September. Of course, the distribution of that rain was wildly uneven: 13.98 inches came over just three days during Helene, and after the storm, Asheville had only 0.03 inches in October and 2.09 inches in November.

Even away from Helene’s heaviest rain, it still finished as the 13th-wettest fall on record in Raleigh with 15.47 inches, or 3.63 inches above normal. That rain was also heavily front-loaded, with 13.02 inches during the 3rd-wettest September on record, then only 0.11 inches in the 7th-driest October on record and 2.34 inches in a closer-to-normal November.

For coastal areas that missed out on the September rain, it ended up as a dry season overall. Elizabeth City had its 9th-driest fall since 1934, with less than half of its normal rainfall: 5.28 inches compared to an average of 11.12 inches. In New Bern, it was the 15th-driest fall on record, as the seasonal total of 7.35 inches was 5.87 inches below normal.

A much more consistent story this fall was the warmth. It may have been most noticeable in November with the 80-degree days and delayed first freeze, but our temperatures were above-normal for all three fall months, including our 50th-warmest September and 42nd-warmest October on record statewide.

Locally, it was the 3rd-warmest fall on record in Hickory and tied for the 3rd-warmest in Raleigh. Asheville had its 4th-warmest fall, and it was the 5th-warmest for Charlotte. It ranked among the top ten warmest falls on record at other sites including Lumberton (tied for the 6th-warmest), Lenoir (9th-warmest), and Greensboro (tied for the 10th-warmest).

At most of those sites, this fall’s average temperatures were similar to those in 2016, which was also notable for its extremes. That October, eastern North Carolina was flooded by Hurricane Matthew while the southern Mountains slid deeper into drought, setting the stage for wildfires to ignite across the landscape in November.

This fall, the Mountains faced another natural disaster in Helene, but thankfully no major fire activity during the dry spell that followed. Instead, those final two months of the fall offered a chance to assess the estimated $53.6 billion in damage from the storm – more than triple the $17 billion caused by Hurricane Florence in 2018 – and begin the cleanup and recovery efforts.

That one event may ultimately define this fall, and indeed this year, in North Carolina’s history. But our weather records will reflect Helene’s place in an overall odd, extreme fall that started wet, flipped to dry, and remained abnormally warm almost up until the Thanksgiving turkeys were thawed.

Discussion about this post