Brain organoids are 3D, lab-grown models designed to mimic the human brain. Scientists normally grow them from stem cells, coaxing them into forming a brain-like structure. In the past decade, they have become increasingly sophisticated and can now replicate multiple types of brain cells, which can communicate with one another.

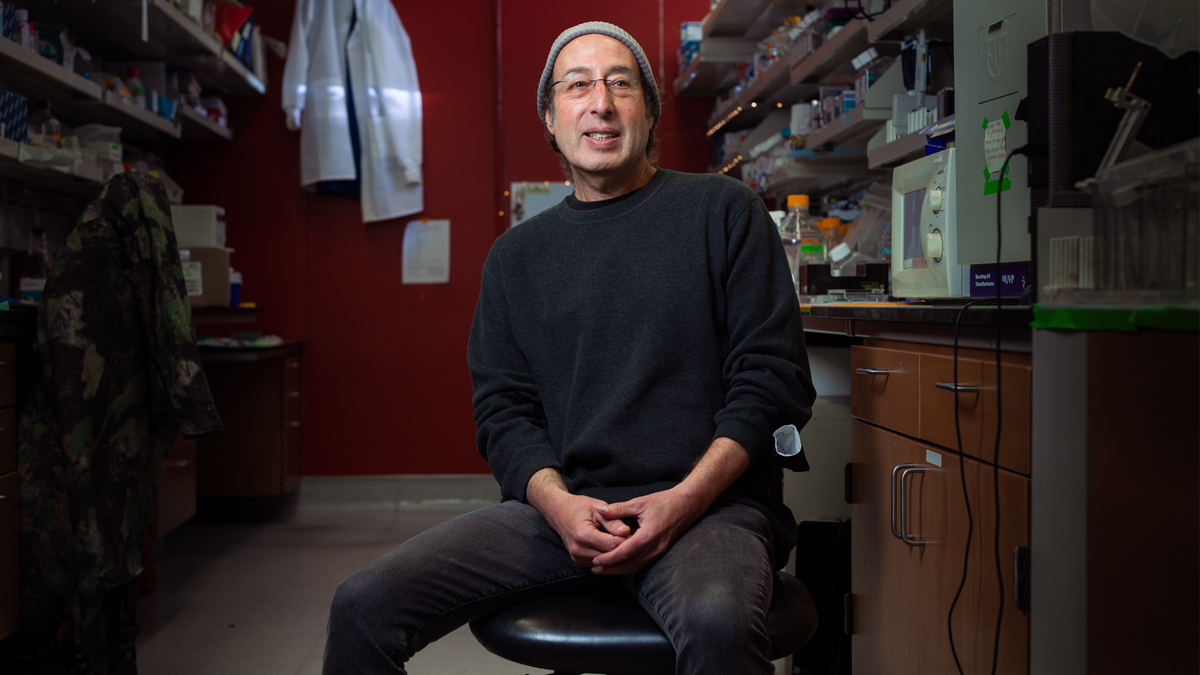

This has led some scientists to question whether brain organoids could ever achieve consciousness. Kenneth Kosik, a neuroscientist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, recently explored that possibility in a perspective article. Live Science spoke with Kosik about how brain organoids are made, how similar they are to human brains and why he believes that brain organoid consciousness is not likely anytime soon.

Related: In a 1st, ‘minibrains’ grown from fetal brain tissue

EC: What are brain organoids, and how do scientists make them?

Kenneth Kosik: A brain organoid is made from stem cells. You can take any person and convert their, say, skin fibroblasts into stem cells, and then differentiate them into neurons. It’s what stem cells are all about — stem cells are called “pluripotent” because they can make any cell in the body.

We spent a fair amount of time before organoid technology came along, taking human-induced pluripotent stem cells and inducing them in a two-dimensional array to look at neuronal differentiation.

So that takes us halfway there. But it only gets us as far as two dimensions. And then the big insight, which came from Yoshiki Sasai in Japan and Madeline Lancaster, was to take these neurons that were beginning to differentiate — cells relatively early in development — and put them in a drop of what’s called Matrigel — a gel that can be either a liquid or a solid depending on the temperature.

So the cells are in this drop, and then the magic happens. Instead of growing in two dimensions, they start to grow in three dimensions. It absolutely fascinates me that when biology begins to explore the third dimension, a very novel biology emerges. Certainly, in two dimensions, these neurons that were growing could achieve a very wide diversity of cell types, but they did not achieve any kind of interesting anatomy.

Once they’re growing in three dimensions, they start to form relationships to each other, kinds of structure and anatomy, that has a very loose resemblance to the brain. And I really emphasize the word “loose,” because there are people that use a misnomer for brain organoids and call them “minibrains.” They’re not brains at all. They are organoids — meaning like the brain.

A question we’re keenly interested in, and many labs are, is that if organoids are like the brain, to what degree do they resemble the brain and to what degree do they differ? And they differ from the brain a lot, so you have to be very careful about interpretations of organoids. Not everybody thinks that organoids are going to be informative for neuroscience because what we find in an organoid may be over-interpretation. But on the other hand, [it] is forming a three-dimensional structure that has some degree of lamination [formation of layers of cells within tissue], it has these rosettes in which, from the center of the rosette, you can progressively see cells becoming more mature as development proceeds, which is very similar to what happens in the brain.

Related: Lab-grown ‘minibrains’ may have just confirmed a leading theory about autism

EC: Are there any brain organoids that accurately capture the whole brain yet?

KK: There is no organoid that captures the whole brain. There are approaches that attempt to capture more of the brain than, say, just the one part that maybe we and other labs are working on. These are called “assembloids.” [Scientists] take stem cells and differentiate them down a pathway that may make a little more ventral [front part of the] brain, or a little more dorsal [back part of the] brain, and they put them together, they fuse them, so that you get more comprehensive fusion — a wider representation, I should say, of brain anatomy.

There are other ways of making organoids that are a little more indiscriminate. They’re not directing the stem cells towards dorsal and ventral, they are putting them all together. That’s a lot of what we do. Those were the techniques that were originated by Lancaster. And in that case, it’s my opinion that when you do it that way, you get a broader representation of cell types. That’s what you gain, but you sacrifice anatomical accuracy because when you make an assembloid, the anatomy is not great. But when you do it without differentiating toward dorsal and ventral and you put it all together, the anatomy becomes even more problematic.

EC: As you alluded to, these organoids are similar to human brains, but there’s some key physiological differences. Can you explain those?

KK: So, one similarity right away is that you see a lot of spiking going on.

(Editor’s note: Kosik is referring to the fact that, when an organoid is hooked up to electrodes, this triggers electrical spikes, or signals, transmitted between neurons.)

It’s quite remarkable, and underlying this is the notion, which is probably what intrigues me the most, that all of this activity is spontaneous: it just arises based on the assembly of the neurons.

And now we can look at the relationships of those spikes. When you do that, you can ask the question, well, if I see neuron A firing, what’s the likelihood that I’ll see neuron B firing? I’m going to look at the binary relationships among all of them and I’m doing it with the filter that when neuron A fires I’m only going to look at when another neuron fires within 5 milliseconds. Why 5 milliseconds? Because that’s about the time in which it takes for transmission to occur across the synapse. (Editor’s note: A synapse is the gap between two neurons.)

And when we do that, you can see that they form a network. You connect A and B, and then you connect C and D, and then A and C. You can see that the neurons are talking to each other and this arises spontaneously.

That is one example of the way in which an organoid does something that will spontaneously resemble what happens in the brain.

The way I look at an organoid, it is a vehicle that has the capacity to encode experience and information if that experience were available to it — but it’s not. It has no eyes, ears, nose or mouth — nothing’s coming in. But the insight here is that the organoid can set up spontaneous organization of its neurons so that it has the capacity to encode information, when and if it becomes available. That’s just a hypothesis.

Related: Lab-grown ‘minibrains’ help reveal why traumatic brain injury raises dementia risk

EC: Do you think that brain organoids will ever achieve consciousness?

KK: So that’s where things get a little mysterious. I think that those kinds of questions are predicated on this term that people have a lot of trouble defining: consciousness.

[Based on currently fashionable theories of consciousness] I would say, “No, it doesn’t even come close.”

Related: Mini model of human embryonic brain and spinal cord grown in lab

EC: You spoke about the fact that organoids have shown some capacity to encode information, but they don’t have the experience to do this in the first place. What would happen if, hypothetically, a human brain organoid was transplanted into an animal? Could it then achieve consciousness?

KK: Let’s break that down. Before it is transplanted into an animal, some people would say the animal already has consciousness and some people would say [it does] not. So, right away, we get into this difficulty about where in the animal kingdom does consciousness begin? So, let’s reframe the question. If you then took an animal, which may or may not have some degree of consciousness, and you transplant in a human organoid, would you confer consciousness on that animal or would you enhance consciousness, or would you even get something that resembled human consciousness in the animal? I don’t know the answer to any of those questions.

We can do these hybrids now — so it’s a good question. But the evaluation of consciousness now, because of all the problems as to what consciousness is, is still going to be an open question.

Related: Could mini space-grown organs be our ‘cancer moonshot’?

EC: Do we have an idea of rough timescales —, is consciousness something that could happen in the near future, after, say, a certain number of years, or is it still really uncertain at this point?

KK: Technology is moving very fast. One place where we may begin to push the boundary is in the so-called cyborgs, or organoid interfaces. That would be one direction that could be interesting. Maybe a little bit toward consciousness, but even more so toward developing the implementation of human abilities in one of these synthetic systems.

EC: Can you think of any obvious benefits and drawbacks of these organoids being able to achieve consciousness?

KK: We know so little about neuropsychiatric conditions. Neuropsychiatric drugs are developed without understanding any deep physiology. All of that could be done, I think, with organoids. I think as disease models, it could be very, very useful [for them to achieve consciousness].

The dream state that I have is to develop them as computational systems because, right now, to do the kinds of very expensive computations that are required for ChatGPT and many of these large language models, these take hundreds of millions of dollars to develop. They require a server farm of energy to keep them going. We’re really just running out of computer power. Yet, the brain does a lot of this stuff on 20 watts. So, a big interest for me is, “Can organoids, if not solve, contribute to the huge demands that we’re making on the energy system by tapping into the highly efficient way in which the brain, and presumably the organoid, can handle information?”

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited and condensed.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/34/31/3431771d-41e2-4f97-aed2-c5f1df5295da/gettyimages-1441066266_web.jpg)

Discussion about this post