Modified ground used to fill Wellington’s valleys nearly 100 years ago is growing old and putting the city at greater risk of landslips, a geomorphologist has warned.

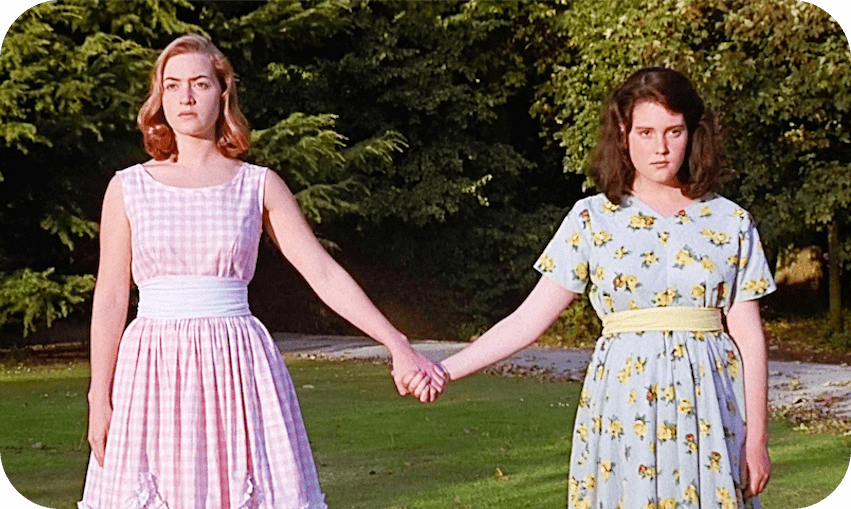

A large slip came down on Woodhouse Avenue, Karori.

Photo: RNZ / Kevin McCarthy

Earthquake Commission assessors in Wellington are about to get busy, after another spate of landslips struck the drenched capital this week.

GNS Science engineering geomorphologist Brenda Rosser told Morning Report landslips were a normal occurrence in the region but slowly deteriorating modified ground had increased the risk.

“In Wellington, we do have a lot of slips but it’s kind of a normal thing, we get them every winter when it rains a lot the slopes are saturated also our beautiful city is built on hilly terrain so we’re sort of in that landscape where there’s the possibility of slopes failing.

“On top of that we’ve also got a lot of modified ground so that’s cuts and fills and a lot of them are pretty old these days, getting up around 100 years old.”

Fills and cuts were created when people wanted to fill in valleys in order to build more houses and many of them were created with techniques and methods that were now outdated, Rosser said.

“We now have better techniques for building those fill slopes, a lot of them were built a long time ago in the 20s and 30s so those slopes we’re finding that there are more landslips occurring on those slopes rather than natural slopes.”

The Wellington fault line which runs through the city had weakened some of the slopes in the region over time due to continual movement, she said.

Cracking in structural concrete and doors not being able to close were early warning signs of the possibility of a landslip and residents who noticed these signs were urged to contact Wellington City Council or the relevant regional authority, Rosser said.

Landslip damage is deemed a natural disaster so residential land is covered by EQC however there are still misconceptions about what can and can’t be claimed for.

EQC chief executive Tina Mitchell told Morning Report it had one of the only policies which not only protected a residential house but also the land underneath the house.

In recent slips in Wellington, land was seen to slip into properties from outside the affected home’s property boundaries.

Regardless of where a slip originated, if it caused damage to a property covered by the insurer they were obliged to help, Mitchell said.

“It all depends on where the damage occurs as to whether or not we cover it… it doesn’t really matter where the land comes from if it slides into the area that we cover which is that footprint under the house and then that eight metre perimeter or your driveway, then we’re interested and we want to have a look at it and see if we can help customers through that,” Mitchell said.

Insurance policies often covered an eight metre perimeter around a house, any structures on the property and part of the driveway, she said.

The unexpected nature of landslips meant affected homeowners were often asked to evacuate at short notice and temporary accommodation tended to be covered by a mix of EQC and private insurance, she said.

EQC played a multi-faceted role in the response to natural disasters, using research and science to understand the risks associated with different types of land while also being at hand to assist in the case of a disaster, she said.

The commission received 270 claims of landslip damage from across the country in the last five weeks, this included 75 claims in Wellington, 50 in Christchurch and 40 in Auckland.

It was too early to tell whether the rate of landslips was on the rise but EQC was working with the Ministry of Environment to track that over time, Mitchell said.

“People might be surprised to know landslips are actually our most common claim anyway over the history of the scheme because of the topography of our country and our weather patterns that is probably more common for us than an earthquake in terms of damage,” she said.

A landslip blocks The Terrace in Wellington

Photo: RNZ / Charlotte Cook

There were 1100 landslip related claims made to EQC in the last financial year, she said.

Homeowners whose properties were damaged by a landslip would be eligible for $150,000 to assist with damage to the house, any more would require the assistance of private insurance.

Damage to the land was treated separately under EQC’s policy, utilising geotechnical evaluation to help determine the scale of the damage and the cost to repair.

“Part of our scheme actually does cover for imminent damage as well which is another unique thing, so not only the damage that has occurred but the experts can say ‘We think that land will move further in the next 12 months’,” she said.

The value of the land damaged by a slip varied from region to region, with land in Auckland often valued higher than land in the regions, she said.

While there was a cap on how much cover EQC would offer in land damage, it was complex and Mitchell urged people with concerns to contact the commission directly.

Discussion about this post