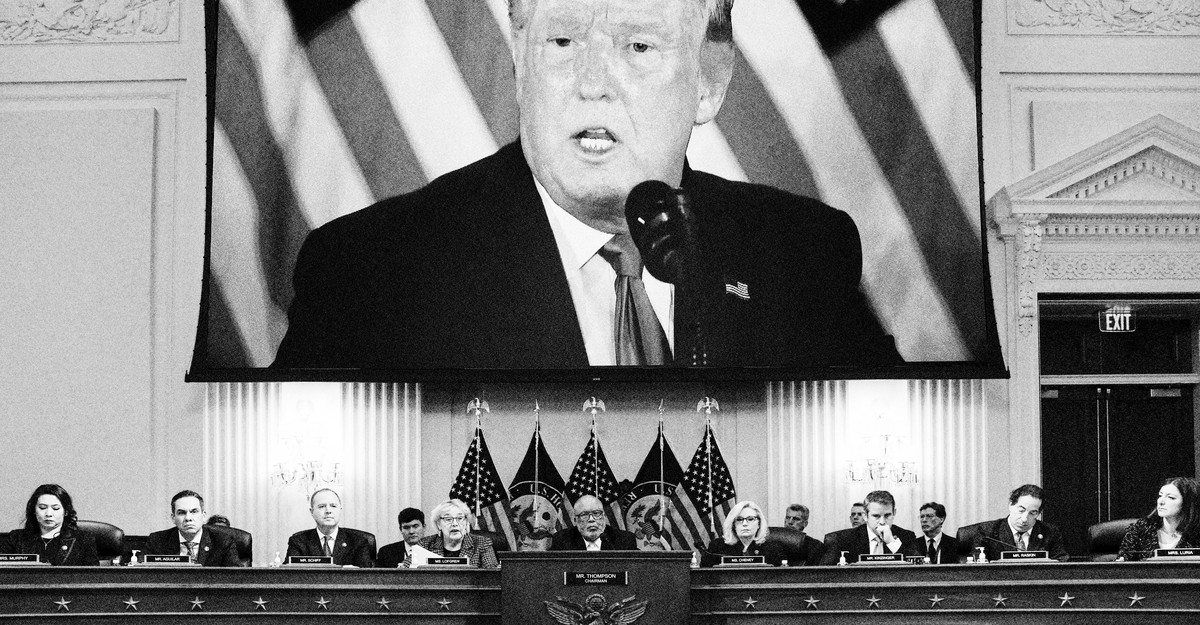

The congressional committee investigating the January 6 insurrection delivered a comprehensive and compelling case for the criminal prosecution of Donald Trump and his closest allies for their attempt to overturn the 2020 election.

But the committee zoomed in so tightly on the culpability of Trump and his inner circle that it largely cropped out the dozens of other state and federal Republican officials who supported or enabled the president’s multifaceted, months-long plot. The committee downplayed the involvement of the legion of local Republican officials who enlisted as fake electors and said almost nothing about the dozens of congressional Republicans who supported Trump’s efforts—even to the point, in one case, of urging him to declare “Marshall Law” to overturn the result.

With these choices, the committee likely increased the odds that Trump and his allies will face personal accountability—but diminished the prospect of a complete reckoning within the GOP.

That reality points to the larger question lingering over the committee’s final report: Would convicting Trump defang the threat to democracy that culminated on January 6, or does that require a much broader confrontation with all of the forces in extremist movements, and even the mainstream Republican coalition, that rallied behind Trump’s efforts?

“If we imagine” that preventing another assault on the democratic process “is only about preventing the misconduct of a single person,” Grant Tudor, a policy advocate at the nonpartisan group Protect Democracy, told me, “we are probably not setting up ourselves for success.”

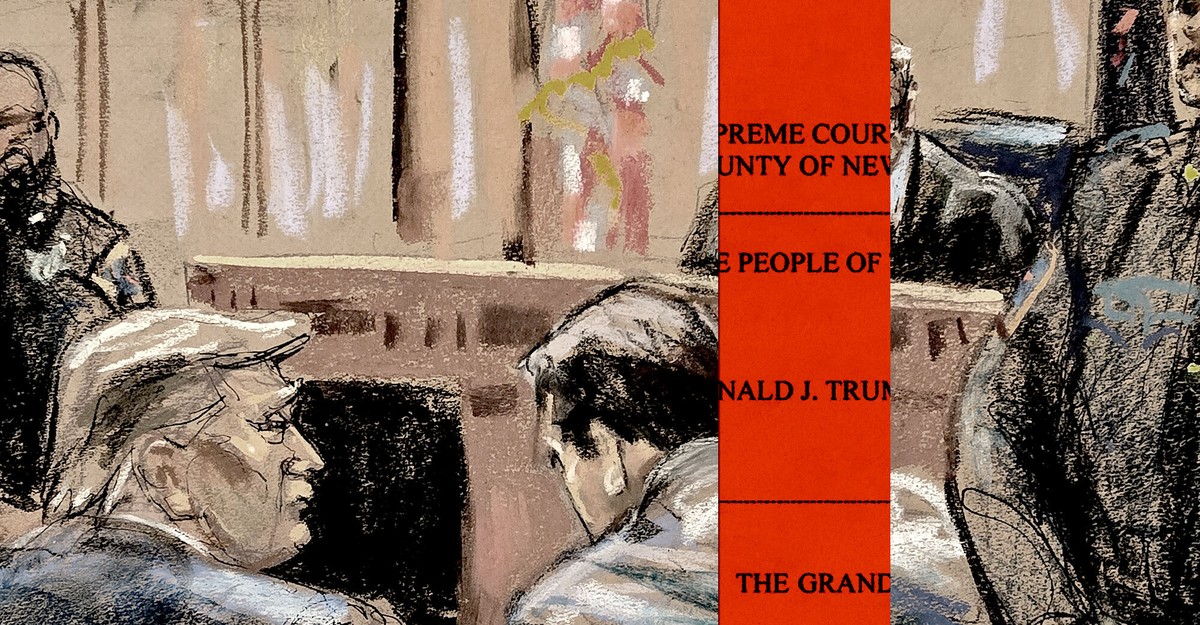

Both the 154-page executive summary unveiled Monday and the 845-page final report released last night made clear that the committee is focused preponderantly on Trump. The summary in particular read more like a draft criminal indictment than a typical congressional report. It contained breathtaking detail on Trump’s efforts to overturn the election and concluded with an extensive legal analysis recommending that the Justice Department indict Trump on four separate offenses, including obstruction of a government proceeding and providing “aid and comfort” to an insurrection.

Norm Eisen, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and the former special counsel to the House Judiciary Committee during the first Trump impeachment, told me the report showed that the committee members and staff “were thinking like prosecutors.” The report’s structure, he said, made clear that for the committee, criminal referrals for Trump and his closest allies were the endpoint that all of the hearings were building toward. “I think they believe that it’s important not to dilute the narrative,” he said. “The utmost imperative is to have some actual consequences and to tell a story to the American people.” Harry Litman, a former U.S. attorney who has closely followed the investigation, agreed that the report underscored the committee’s prioritization of a single goal: making the case that the Justice Department should prosecute Trump and some of the people around him.

“If they wind up with Trump facing charges, I think they will see it as a victory,” Litman told me. “My sense is they are also a little suspicious about the [Justice] Department; they think it’s overly conservative or wussy and if they served up too big an agenda to them, it might have been rejected. The real focus was on Trump.”

In one sense, the committee’s single-minded focus on Trump has already recorded a significant though largely unrecognized achievement. Although there’s no exact parallel to what the Justice Department now faces, in scandals during previous decades, many people thought it would be too divisive and turbulent for one administration to “look back” with criminal proceedings against a former administration’s officials. President Gerald Ford raised that argument when he pardoned his disgraced predecessor Richard Nixon, who had resigned while facing impeachment over the Watergate scandal, in 1974. Barack Obama made a similar case in 2009 when he opted against prosecuting officials from the George W. Bush administration for the torture of alleged terrorists. (“Nothing will be gained by spending our time and energy laying blame for the past,” Obama said at the time.)

As Tudor pointed out, it is a measure of the committee’s impact that virtually no political or opinion leaders outside of hard-core Trump allies are making such arguments against looking back. If anything, the opposite argument—that the real risk to U.S. society would come from not holding Trump accountable—is much more common.

“There are very few folks in elite opinion-making who are not advocating for accountability in some form, and that was not a given two years ago,” Tudor told me.

Yet Tudor is one of several experts I spoke with who expressed ambivalence about the committee’s choice to focus so tightly on Trump while downplaying the role of other Republicans, either in the states or in Congress. “I think it’s an important lost opportunity,” he said, that could “narrow the public’s understanding as to the totality of what happened and, in some respects, to risk trivializing it.”

Bill Kristol, the longtime conservative strategist turned staunch Trump critic, similarly told me that although he believes the committee was mostly correct to focus its limited time and resources primarily on Trump’s role, the report “doesn’t quite convey how much the antidemocratic, authoritarian sentiments have metastasized” across the GOP.

Perhaps the most surprising element of the executive summary was its treatment of the dozens of state Republicans who signed on as “fake electors,” who Trump hoped could supplant the actual electors pledged to Joe Biden in the decisive states. The committee suggested that the fake electors—some of whom face federal and state investigations for their actions—were largely duped by Trump and his allies. “Multiple Republicans who were persuaded to sign the fake certificates also testified that they felt misled or betrayed, and would not have done so had they known that the fake votes would be used on January 6th without an intervening court ruling,” the committee wrote. Likewise, the report portrays Republican National Committee Chair Ronna Romney McDaniel, who agreed to help organize the fake electors, as more of a victim than an ally in the effort. The full report does note that “some officials eagerly assisted President Trump with his plans,” but it identifies only one by name: Doug Mastriano, the GOP state senator and losing Pennsylvania gubernatorial candidate this year. Even more than the executive summary, the full report emphasizes testimony from the fake electors in which they claimed to harbor doubts and concerns about the scheme.

Eisen, a co-author of a recent Brookings Institution report on the fake electors, told me that the committee seemed “to go out of their way” to give the fake electors the benefit of the doubt. Some of them may have been misled, he said, and in other cases, it’s not clear whether their actions cross the standard for criminal liability. But, Eisen said, “if you ask me do I think these fake electors knew exactly what was going on, I believe a bunch of them did.” When the fake electors met in Georgia, for instance, Eisen said that they already knew Trump “had not won the state, it was clear he had not won in court and had no prospect of winning in court, they were invited to the gathering of the fake electors in secrecy, and they knew that the governor had not and would not sign these fake electoral certificates.” It’s hard to view the participants in such a process as innocent dupes.

The executive summary and final report both said very little about the role of other members of Congress in Trump’s drive to overturn the election. The committee did recommend Ethics Committee investigations of four House Republicans who had defied its subpoenas (including GOP Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy, the presumptive incoming speaker). And it identified GOP Representative Jim Jordan, the incoming chair of the House Judiciary Committee, as “a significant player in President Trump’s efforts” while also citing the sustained involvement of Representatives Scott Perry and Andy Biggs.

But neither the executive summary nor the full report chose quoted exchanges involving House and Senate Republicans in the trove of texts the committee obtained from former White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows. The website Talking Points Memo, quoting from those texts, recently reported that 34 congressional Republicans exchanged ideas with Meadows on how to overturn the election, including the suggestion from Representative Ralph Norman of South Carolina that Trump simply declare “Marshall Law” to remain in power. Even Representative Adam Schiff of California, a member of the committee, acknowledged in an op-ed published today that the report devoted “scant attention …[to] the willingness of so many members of Congress to vote to overturn it.”

Nor did the committee recommend disciplinary action against the House members who strategized with Meadows or Trump about overturning the result—although it did say that such members “should be questioned in a public forum about their advance knowledge of and role in President Trump’s plan to prevent the peaceful transition of power.” (While one of the committee’s concluding recommendations was that lawyers who participated in the efforts to overturn the election face disciplinary action, the report is silent on whether that same standard should apply to members of Congress.) In that, the committee stopped short of the call from a bipartisan group of former House members for discipline (potentially to the point of expulsion) against any participants in Trump’s plot. “Surely, taking part in an effort to overturn an election warrants an institutional response; previous colleagues have been investigated and disciplined for far less,” the group wrote.

By any measure, experts agree, the January 6 committee has provided a model of tenacity in investigation and creativity in presentation. The record it has compiled offers both a powerful testament for history and a spur to immediate action by the Justice Department. It has buried, under a mountain of evidence, the Trump apologists who tried to whitewash the riot as “a normal tourist visit” or minimize the former president’s responsibility for it. In all of these ways, the committee has made it more difficult for Trump to obscure how gravely he abused the power of the presidency as he begins his campaign to re-obtain it. As Tudor said, “It’s pretty hard to imagine January 6 would still be headline news day in and day out absent the committee’s work.”

But Trump could not have mounted such a threat to American democracy alone. Thousands of far-right extremists responded to his call to assemble in Washington. Seventeen Republican state attorneys general signed on to a lawsuit to invalidate the election results in key states; 139 Republican House members and eight GOP senators voted to reject the outcome even after the riot on January 6. Nearly three dozen congressional Republicans exchanged ideas with Meadows on how to overturn the result, or exhorted him to do so. Dozens of prominent Republicans across the key battleground states signed on as fake electors. Nearly 300 Republicans who echoed Trump’s lies about the 2020 election were nominated in November—more than half of all GOP candidates, according to The Washington Post. And although many of the highest-profile election deniers were defeated, about 170 deniers won their campaign and now hold office, where they could be in position to threaten the integrity of future elections.

The January 6 committee’s dogged investigation has stripped Trump’s defenses and revealed the full magnitude of his assault on democracy. But whatever happens next to Trump, it would be naive to assume that the committee has extinguished, or even fully mapped, a threat that has now spread far beyond him.

Discussion about this post