One person has died in New Hampshire after contracting the mosquito-borne virus Eastern equine encephalitis, and two others in the Northeast have been infected this summer with the rare disease.

Health officials in the Northeast said that there was an elevated risk for the virus and urged residents to take precautions between dusk and dawn, when mosquitoes are most active.

What is E.E.E.?

The disease, like West Nile virus, is transmitted by mosquitoes, but E.E.E. has a higher death rate and is more rare. It is not contagious from person to person.

There is no treatment for the disease, and about 30 percent of people who get it die, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Many people who survive the illness have continuing neurological problems.

How common is it?

There are only a few cases of the disease each year in the United States, according to the C.D.C., and most of the cases are in eastern or Gulf Coast states.

The states that have reported cases this year said it was the first time that they had found the virus in residents in years.

The New Hampshire Department of Public Health said on Tuesday that an adult in Hampstead who had tested positive for the virus had died. It was the first reported infection in the state since 2014, when the Health Department identified three human cases, including two deaths.

Earlier this month, the Vermont Department of Health said that a man in his 40s from Chittenden County was the first person identified with the disease in the state since 2012, when two people contracted E.E.E. and died. The Chittenden County resident was hospitalized in July and left the hospital a week later.

The Massachusetts Department of Public Health said this month that a man in his 80s who was exposed in Worcester County was the first person identified with the disease in the state since 2020.

There have been around 115 cases of the virus in Massachusetts since 1938, when the virus was first identified, according to the state’s public health department. There was an outbreak in 2019 and 2020 that included 17 cases with seven fatalities.

How to avoid it

In areas at high risk of the virus, people can reduce their risk of getting bitten by an infected mosquito by staying indoors between dusk and dawn. People who are outdoors should wear long pants and long-sleeve shirts and socks and use repellent.

At home, people should make sure their window screens do not have any holes and are attached tightly to doors and windows. They should also remove standing water from their property.

The virus is most often found in and around freshwater, hardwood swamps. “If you live in an area that has that kind of habitat, you should be more aware that there’s potential for it,” said Dawn Wesson, an associate professor in the Department of Tropical Medicine at Tulane University in New Orleans.

The risk of the disease remains until the first hard frost, which kills mosquitoes.

What are the symptoms?

Most people who are bit by an infected mosquito and contract the virus do not become ill.

People who do become ill usually show symptoms starting from four to 10 days after a bite, the C.D.C. said. They can experience fever, chills, body aches and joint pain.

The infection can also lead to neurological disease, which can include meningitis, and encephalitis, the inflammation of the brain. Symptoms of this type of an infection include fever, headache, vomiting, diarrhea, seizures, behavioral changes, drowsiness and coma.

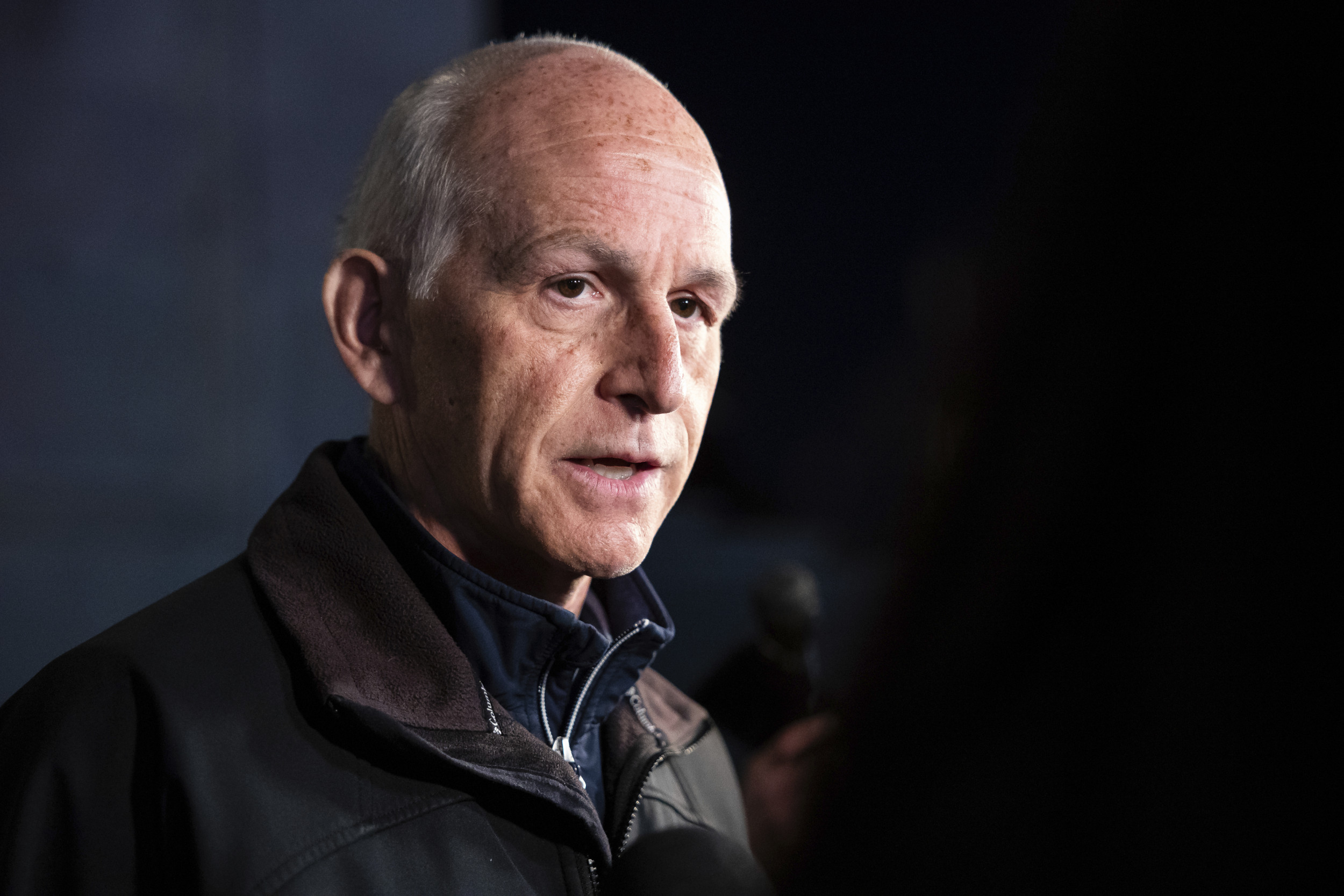

“Among the 4 to 5 percent that get infected and get the disease, only about a third of those people will get the most severe and awful version of the disease, which is the encephalitis,” said Stephen Rich, a microbiology professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

How have the affected areas responded?

There are 10 municipalities in Massachusetts considered at high or critical risk for E.E.E. A high-risk level means the conditions are likely to lead to a person in the area getting the virus, and a critical-risk level means a person in the area has been identified with it.

Dr. Rich, who is also the director of the New England Center of Excellence in Vector-Borne Diseases, said Massachusetts has an especially robust and rigorous surveillance system for finding mosquito-borne viruses. “The absence in any particular state doesn’t necessarily mean it’s not there,’’ he said. “It could be more of a reflection of less robust surveillance.”

The town of Plymouth, which is about 40 miles south of Boston, said on Friday that it was closing all parks and fields between the hours of dusk to dawn because of the threat of the disease.

Oxford, which is 11 miles south of Worcester, told residents to avoid being outdoors between dusk to dawn. A resident of Oxford was the person the state had identified as being infected with the disease, according to the town manager, Jennifer Callahan.

In a memo last week, Ms. Callahan said the person was still hospitalized and that their family had told her that the person had “recounted through the years they never get bit by mosquitoes,” but had said just before they became symptomatic that they had recently been bitten.

Trucks have been spraying pesticides in parts of the state to target the mosquitoes, and spraying is scheduled to expand on Tuesday night to include aerial spraying in Plymouth County and truck spraying in new places.

Health officials in Vermont said they were increasing mosquito collection and testing and urged people in three counties — Chittenden, Grand Isle and Franklin — to take extra steps to protect themselves. In New Hampshire, health officials advised residents to take precautions outside.

Discussion about this post