On November 8, as in any election season, voters will be asked to weigh in on issues such as inflation, crime, and gas prices. Battling for their attention are loaded cultural debates over the end of Roe v. Wade and what children should learn in school. But this is no normal midterm cycle: Few American elections in recent memory have been as threatened by the specter of political violence and democratic dissolution as this one. Last week, a man attacked Nancy Pelosi’s husband with a hammer in the couple’s San Francisco home; Donald Trump’s false claim that he was the rightful victor of the 2020 presidential election continues to cast a long shadow over the integrity of the democratic process; hundreds of candidates who deny the legitimacy of Joe Biden’s election will appear on ballots.

Ahead of the midterms, Atlantic staff and contributors are offering reading suggestions for what feel like unprecedented times. Some of their choices are works of history; others lie more in the realm of theory; some deal with other countries’ systems. But each contains wisdom or insight on a central question: How do we understand the state of American politics today?

Spin Dictators, by Sergei Guriev and Daniel Treisman

At first glance, Spin Dictators might not seem relevant to U.S. elections. The book describes new forms of dictatorship based not on fear or terror, but on manipulating media and undermining democratic institutions. To create a mass following, these new dictators set one part of society against another, exacerbating polarization and mutual distrust. Instead of establishing an old-fashioned, top-down cult of personality, they borrow from the entertainment world to build their popularity, relying on their followers to create memes and merchandise celebrating them. Guriev and Treisman’s examples are drawn from places such as Russia, Venezuela, Singapore, and Kazakhstan, but they could be writing about some American politicians too. U.S. voters will find it useful to read this book and then ask themselves whether any of the candidates in their local senatorial or gubernatorial race have explicitly adopted the language and tactics originally created by modern autocrats. — Anne Applebaum

The Age of Reform, by Richard Hofstadter

History can’t fully explain the present or predict the future, but it can help us understand the patterns of contemporary politics and the likely paths ahead. In 1955, Hofstadter, one of the great American historians of the 20th century, published The Age of Reform—a political and social history of the years 1890 to 1940, the period of populism, progressivism, and the New Deal. Rapid technological change, monopoly power, deep inequality, endemic corruption, mass immigration, nativist demagogues, the transformation of both political parties, repeated efforts at reform, recurring spasms of reaction: Perhaps no other age so resembles our own. Hofstadter is brilliant at analyzing types that feel quite familiar to us today—the crusading urban progressive, the small-town conspiracy theorist. He was a liberal who sympathized with the passion for progress while unsentimentally diagnosing its illiberal ideas and motives. The fevered moralism of that age seems a long way from the paralyzing cynicism of ours. But reading Hofstadter will remind you that reform and reaction not only follow each other, but also often coexist in the same moment; neither ever has the last word. Americans are always dreaming of a better country, and some have actually made it so. — George Packer

One Mighty and Irresistible Tide, by Jia Lynn Yang

Our broken immigration system has been a favorite topic of Republicans on the stump during this midterm-election cycle. But many voters are struggling to understand how Congress has failed for decades to fix it, particularly when the fate of Dreamers—people who were brought to the United States illegally as children—has been unresolved for more than 10 years, and there is nothing to prevent a future president from reviving the use of family separation as an enforcement tactic. One Mighty and Irresistible Tide provides some helpful explanations by tracing another fraught period in history. Yang, who heads The New York Times’ national desk, vividly profiles key figures, such as the New York Representative Emanuel Celler, in the 40-year battle to repeal the ethnic quotas signed into law in 1924. Celler’s steady fight finally ended in 1965, during the civil-rights movement. It makes an implicit case that the moment some in Congress today seem to be waiting for—one where a universal consensus can be established, and reforming the system carries no political risk—will never come, and that challenging fearmongering rhetoric about immigrants remains as important as ever. — Caitlin Dickerson

Devil’s Bargain, by Joshua Green

How did extremism move from the outer edge of our discourse to the very center of our politics? In the final days before yet another existential election, I’m revisiting Devil’s Bargain. Green, a former senior editor at The Atlantic, was among the first journalists to recognize the unique threat that Steve Bannon posed to the future of the American experiment. Devil’s Bargain chronicles Bannon’s journey from Goldman Sachs to the inner workings of then-candidate Donald Trump’s head. It also illustrates the many ways in which influential money moves around right-wing circles and shapes our democracy. Some critics have accused Green of overstating Bannon’s influence, but five years after the book’s publication, Bannon is neither gone nor forgotten. Although he ultimately served less than a year in Trump’s White House, he was the eventual recipient of a presidential pardon. Last month, he was sentenced to four months in prison for a different offense—defying a subpoena from the January 6 committee. His old boss, meanwhile, appears to be preparing to retake the White House. — John Hendrickson

Public Opinion, by Walter Lippmann

One of the best things you can say about Lippmann’s 1922 classic is also one of the worst things you can say about this moment: Public Opinion, at 100, has never been more relevant. Lippmann’s study of the human mind and the body politic, produced in the aftermath of World War I, analyzes the impact of a new mass-media system—on government, on news, on “the pictures in our heads.” It applies the lessons of psychology, then a nascent field, to electoral politics. It warns of how easily propaganda, that evasive weapon of war, can become banal. The book created a lasting lexicon: Lippmann coined stereotype as a category of thought; he discussed mediums and “pseudo-environments” long before other thinkers would expand the concepts; he observed the totalizing power of narrative decades before postmodernists would simulate that idea. Public Opinion saturates political discourse so completely that its insights, today, might seem obvious. In truth, they are ominous. Democracy is the work of minds made manifest; how will it proceed when “the pictures in our heads” are blurred by lies? — Megan Garber

Crabgrass Frontier, by Kenneth T. Jackson

Jackson’s 1985 work, Crabgrass Frontier, is beloved by urban historians, and it underscores how novel America’s urban geography really is. Prior to 1815, Jackson writes, the suburbs were exactly that—the outlying area of the city, “in every way inferior to the core.” Over the next two centuries, a reversal of fortunes would make single-family homes in peripheral communities crucial to the American Dream. This change reflected and reinforced a new way of life—one where work, home, and play were cleaved from one another; where privacy and the nuclear family became fundamental; and where races and classes were physically separated. The political ramifications remain, visible in the stark differences in the quality of public services in cities and suburbs. Entrenched low-density homeownership has been a primary driver in the segregation that continues to define American life. Ahead of momentous elections, Crabgrass Frontier is a potent reminder that what’s built in one era shapes the next. We are living in a present constructed by people who could never have imagined our lives. As the nation faces an inflection point—a startling shortage of housing, and a dearth of renewable-energy and mass-transit infrastructure, all in the face of climate emergency—what policy makers build today will determine the fate of our descendants. — Jerusalem Demsas

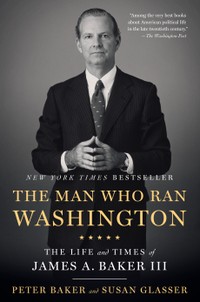

The Man Who Ran Washington, by Peter Baker and Susan Glasser

James Baker is no longer a power player in Washington. The former secretary of state’s influence peaked during the presidencies of Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush, two leaders whom the Trump wing of the Republican Party has all but renounced. Yet the journalists Baker (unrelated) and Glasser show that Baker, despite thinking himself above the fray, is not so out of place in Donald Trump’s GOP after all. Baker, now 92, wants to be remembered as a statesman, not as a campaign operative. But his most durable legacy might be his contributions to a party whose zeal for winning and holding power at nearly any cost has overtaken its commitment to ideology and principle. The authors smartly frame Baker’s story around his late-in-life struggle over whether to vote for Trump, a man he plainly can’t stand personally or politically. But Baker, clinging to the hope that even in his late 80s he might stay relevant in Washington, ultimately chose party loyalty. He appears now as more of a precursor to our fraught political moment than a throwback to a more genteel one. — Russell Berman

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

%20(2)%20(1).jpg)

Discussion about this post