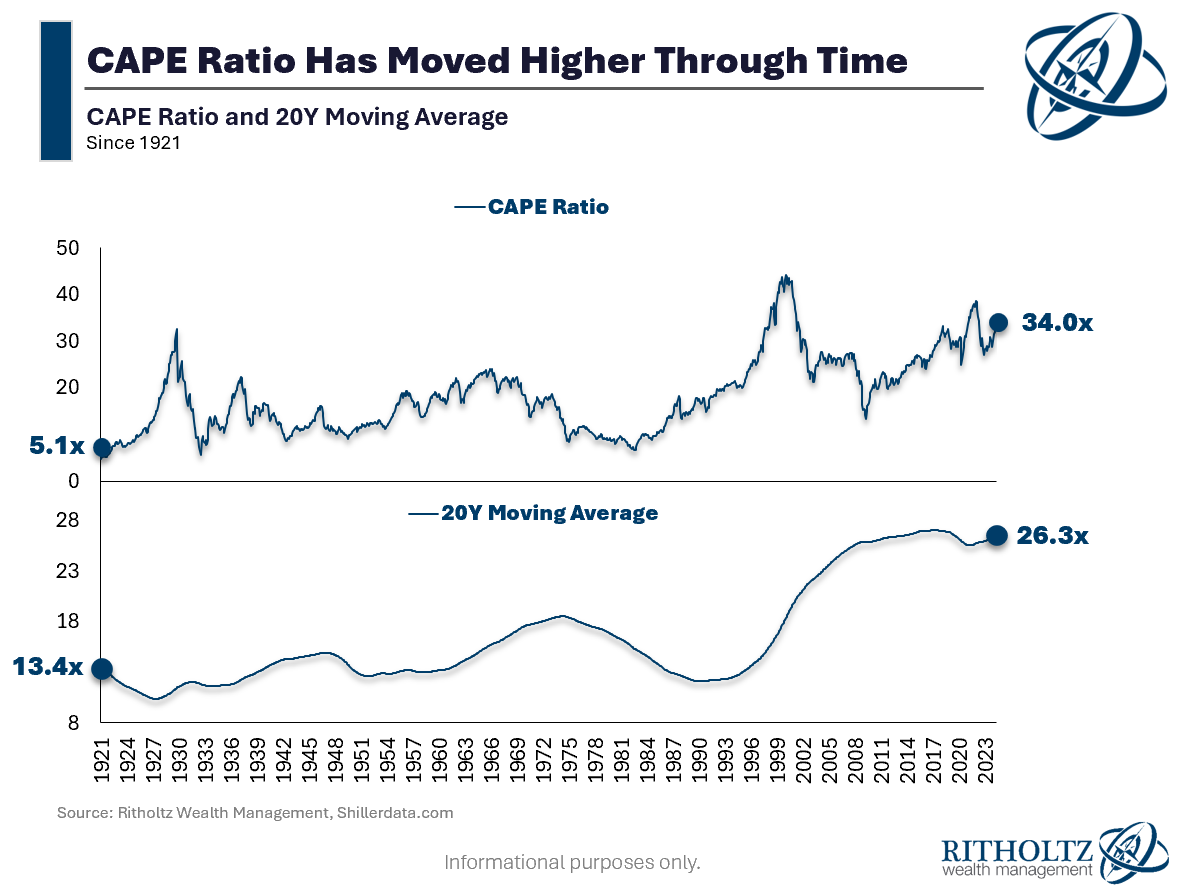

Stocks in the United States are more expensive than they used to be. Like, a lot more.

You used to be able to buy a blue-chip company for fifteen times earnings. There was a time, a normal non-recessionary time, when you could buy the S&P 500 for fifteen times earnings.

Prior to the dotcom bubble, there was only one instance when U.S. stocks traded at 25x times inflation-adjusted earnings over the previous decade. That was the peak of the speculative mania of the Roaring 20s, which was followed by the stock market crash and a Great Depression. The late 90s experience a similar boom-bust cycle. Prior manias, as measured by the CAPE Ratio, appear to be the new steady state, with a CAPE trading at 26x on average for the last twenty years.

So, will we ever go back to the way things were? Are high valuations here to stay? It’s impossible to say for sure. We can’t even pinpoint with certainty why this is happening. And that’s because it’s not just one thing driving the market to higher multiples than they have been in the past. One culprit that gets a lot of airtime are flows into index funds. There’s an overlooked aspect of this that I’d like to discuss, which is where the flows are coming from. Josh wrote about the relentless bid a decade ago, saying :

Almost no matter what happens, each week advisors of every stripe have money to put to work and they’re increasingly agnostic about the news of the day. They’ve all got the same actuarial tables in front of them and they’re well aware that their clients are living longer than ever – hence, a gently increased proportion of their managed accounts are being allocated toward equities. And so they invariably buy and then buy more.

Ten years later and this theory still holds up. I saw another flavor of this recently in a post about Michael Saylor, of all things. “Zack Morris” described the U.S. stock market as having earned a monetary premium, saying:

When you contribute money to your 401k every month, what are you really doing? Are you saving? Or are you investing?

I would contend most people are saving. They have no interest in risking what they’ve already earned, but if they don’t, they are certain to lose it to inflation and debasement.

If people are saving their wealth in the S&P 500 instead of money, that means the equity market has attained a monetary premium.

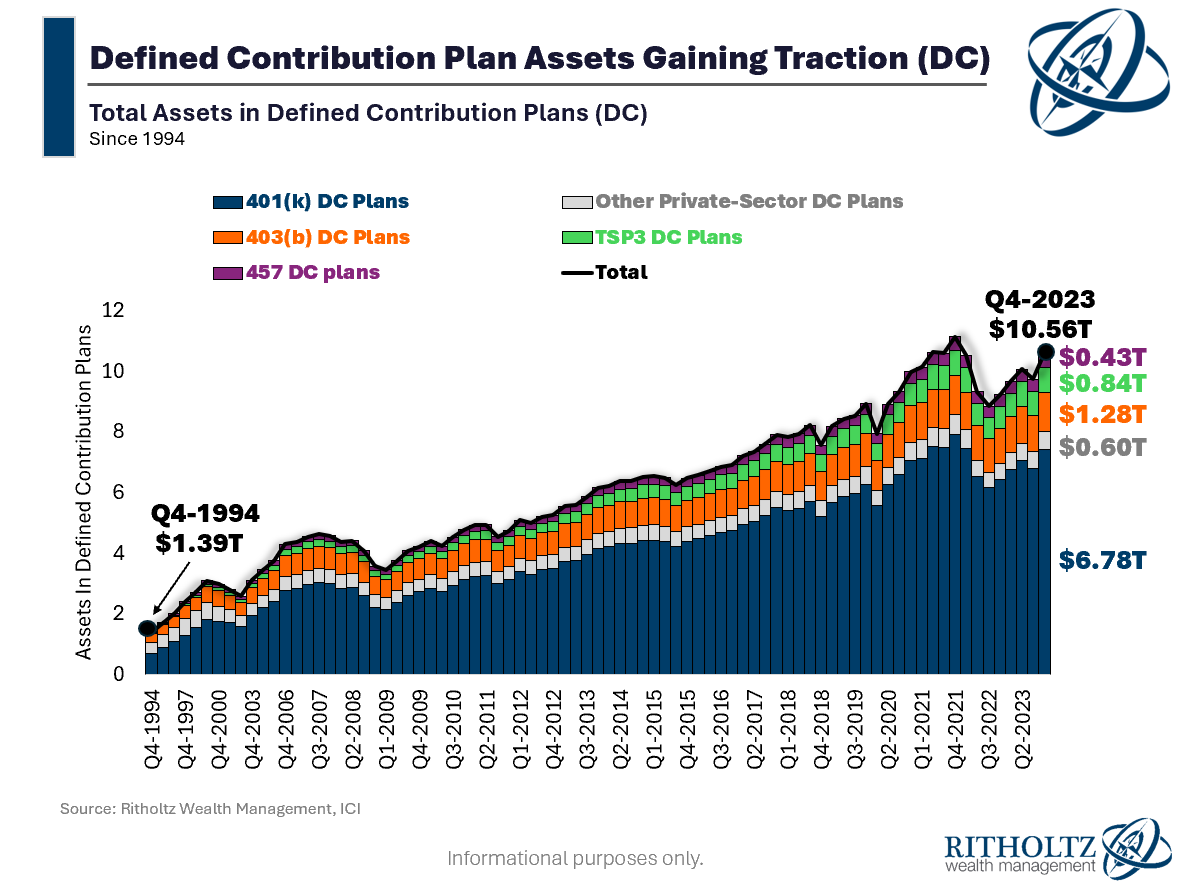

A tidal wave of money is pouring into the market with every paycheck millions of Americans receive. At the end of the 4th quarter, there was $10.56 trillion in Defined Contribution Plans. I don’t think it matters much* whether this money goes into actively managed mutual funds or index funds. The fact that it’s coming in, in this size, every two weeks come hell or high water, is absolutely having an impact on the price of stocks. Specifically, the price relative to whichever underlying fundamental metric you prefer to measure.

The stock market is an infinitely complicated machine, making it difficult to say anything with 100% confidence. So maybe let’s invert, and describe what this picture doesn’t say.

It doesn’t mean we can’t have corrections or bear markets. Since Josh wrote The Relentless Bid, there have been three separate 15% drawdowns.

It doesn’t mean that stocks will trade at these multiples forever.

It doesn’t mean that money coming into the market is guaranteed to lead to positive returns over the next three to five years or beyond.

But I do think Zack Morris is right to describe the U.S. stock market as a savings vehicle as much as an investing one, thereby earning a monetary premium. One of the biggest takeaways from this theory, assuming you agree with some or all of it, is that multiples don’t have to revert to where they had traded historically.

Like I said earlier, nothing ever happens in the market for one reason alone. There are at least a dozen slices of the “why are stocks expensive” pie chart, and I think the savings component is just one piece, albeit a large one.

*I know it matters at the micro level. I’m not sure it matters as much at a macro level.

This content, which contains security-related opinions and/or information, is provided for informational purposes only and should not be relied upon in any manner as professional advice, or an endorsement of any practices, products or services. There can be no guarantees or assurances that the views expressed here will be applicable for any particular facts or circumstances, and should not be relied upon in any manner. You should consult your own advisers as to legal, business, tax, and other related matters concerning any investment.

The commentary in this “post” (including any related blog, podcasts, videos, and social media) reflects the personal opinions, viewpoints, and analyses of the Ritholtz Wealth Management employees providing such comments, and should not be regarded the views of Ritholtz Wealth Management LLC. or its respective affiliates or as a description of advisory services provided by Ritholtz Wealth Management or performance returns of any Ritholtz Wealth Management Investments client.

References to any securities or digital assets, or performance data, are for illustrative purposes only and do not constitute an investment recommendation or offer to provide investment advisory services. Charts and graphs provided within are for informational purposes solely and should not be relied upon when making any investment decision. Past performance is not indicative of future results. The content speaks only as of the date indicated. Any projections, estimates, forecasts, targets, prospects, and/or opinions expressed in these materials are subject to change without notice and may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed by others.

The Compound Media, Inc., an affiliate of Ritholtz Wealth Management, receives payment from various entities for advertisements in affiliated podcasts, blogs and emails. Inclusion of such advertisements does not constitute or imply endorsement, sponsorship or recommendation thereof, or any affiliation therewith, by the Content Creator or by Ritholtz Wealth Management or any of its employees. Investments in securities involve the risk of loss. For additional advertisement disclaimers see here: https://www.ritholtzwealth.com/advertising-disclaimers

Please see disclosures here.

Discussion about this post