Despite its dwindling locations and reduced service, NZ Post remains a pillar in every community, writes Hera Lindsay Bird.

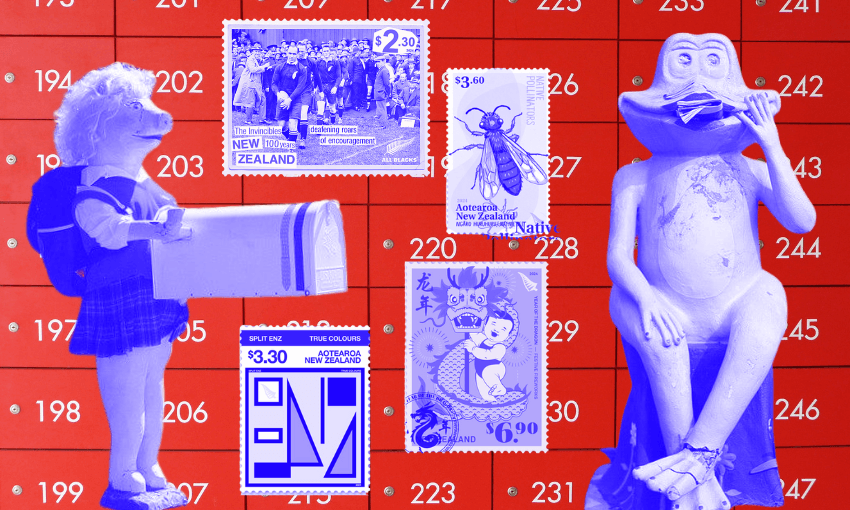

Every Saturday morning I arrive at 7.30am, and enter the post office box lobby. Behind the narrow corridor of identical red letterboxes, there is a locked room, full of ancient Christmas decorations. A malevolent wooden Santa with pale blue eyes stares unblinkingly up at the ceiling, like the figurehead of a great ship, or a drowned Pagan god.

Someone has been here before me, and left a sack of mail. I perch on the edge of a busted office chair and sort the mail into numerical order, redirecting the redirections, and returning the charity fundraising envelopes scribbled over with the legend GONE NO ADDRESS.

In the winter, the post office box lobby is cold, and I can see my breath as I sort the TV guides from the electric bills. But it’s a peaceful time of day, and I find the work interesting, glancing over tropical bird stamps from faraway countries, archeology magazines and religious chain letters. My work is rarely disturbed. Only once have I deposited a letter, to see a disembodied hand reaching in from the other side.

The post office I work at isn’t just a post office, but a bookshop with a side hustle. The vast majority of NZ Post “retail agents” are pre-existing stores that have simply incorporated post into their range of services. There are currently over 800 NZ post retail outlets in NZ but the number is dwindling.

The cause is hardly surprising. In this increasingly digital age, nobody sends mail anymore. Susan Edmunds reported that in 2002, a billion mail items passed through NZ Post. That number is projected to drop to just over 100 million within the next four years. NZ Post is a 100% state-owned enterprise, with an obligation to be self-sustaining and make a profit, although it received a $130 million dollar injection of cash in 2020, in response to the Covid pandemic. NZ Post’s obligations are determined by an agreement with the government, called the postal deed of understanding, which outlines minimum obligations, such as the frequency of mail delivery and the number of postal outlets.

The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) is currently seeking public consultation on a series of proposed changes, which would reduce these obligations. These changes would affect all New Zealanders, but particularly those on the rural delivery network. NZ Post is offering voluntary redundancies in an attempt to reduce its budget by $35 to $40 million dollars this financial year. This doesn’t affect the courier drivers, who are considered “contractors” and must pay for their own ACC costs, vehicles and uniforms.

Working behind the post office counter, I see the change firsthand. I wasn’t prepared for the vast number of young people who have never sent a letter, and need help with what to write on an envelope, and how to affix a stamp. In these heady post-pandemic days, we use a moistened sponge. As a society, the days of stamp-licking are behind us, and not even the new commemorative All Blacks range is enough to induce most customers to extend a wary tongue.

If the PO boxes are full, the letterboxes are empty. Nobody gets much mail these days. The only things which ever shore up in my personal letterbox are hand-delivered racist pamphlets around election time and various community newspapers, which boast charming articles about teenagers fundraising for international badminton tournaments and notices on model train expos. Even junk mail and bills are mostly electronic.

So who still uses the post, and for what?

In my experience? Shoes.

Before I got this job, I never knew how many pairs of shoes were travelling through the New Zealand postal service at any one time. Ordinary post-bags, filled to the brim with used sandals and espadrilles, making their way from one end of the country to the other. I don’t know what this means or how to explain it, only that it’s one of the deep and profound mysteries of the postal service.

The second main thing people use the postal service for is complaining about the postal service. Usually about the price of sending things, which goes up almost every year. I will admit it is scandalously expensive to send a box full of potato chips to a research station in Antarctica, but the fact you can send a box of potato chips to a research station in Antarctica is pretty impressive.

Unlike the mysterious case of the used shoes, I know exactly what everyone is sending overseas, because we have to check and double check every customs form. There are an enormous amount of rules about what you can and can’t send, and how you can and can’t send them. It took me a long time to get to grips with the necessary bureaucracy. Hair-dye, batteries, christmas crackers, magnets, nail polish are all forbidden or restricted items, but you can send live bees through the mail, if packaged appropriately and containing the correct documentation. Thankfully nobody has ever asked.

The postage fees are almost always more expensive than the items being sent. But that’s hardly surprising, as most things being shipped internationally are sentimental. I see a lot of hand-knitted baby booties, and care packages full of pineapple lumps for expatriate adult children.

You see a lot of life over a postal service counter. This week the Americans are all sending their Christmas cards. Last month they were sending their election ballots. The university exams are drawing to a close, which means I’m usually busy helping students package up their suitcases and ship them home to their parents’ addresses. Next year they’ll be back, limping in on Monday morning to return their expensive rental couture.

As the volume of mail decreases, the remaining post shops only get busier, as other NZ Post retail outlets fold or change focus. Everyone needs the postal service, but nobody wants to pay for it. It seems to fit into the larger pattern of New Zealand’s current economic model. Run down hospitals, overburdened libraries, citizens advice bureaus folding left and right. The things which everyone relies on, but which don’t turn a profit.

Obviously, the post has to scale back. Supply and demand, and all that. But it’s particularly rough on our rural communities and older population, who rely on their letterboxes to stay connected with the outside world. It’s already near impossible to participate in society without a smartphone, and we keep making it harder. The other day I served a customer who had driven over an hour and a half, just to send an international package.

This weekend, I watched a colleague intervene in a scam. He was assisting an elderly customer with her customs forms (which have diabolically small print) and after talking to her about what she was sending and why, he became concerned. She had been charged for and sent a number of medical items she didn’t order, and had been informed that unless she shipped them back with an urgent international courier at her personal expense, the company would refuse to refund her card. My colleague recognised the scam immediately, and after a long conversation with the woman and her family, advised her to contact her bank and report the fraud.

The post is more than just a way for you to send anthrax to your local MP (prohibited) or jandals through the mail. Sure, it’s not making tobacco lobby money. But it depresses me to think of a world in which all our essential public services are rundown and automated. No bank tellers. No supermarket cashiers. Just the cheapest international call centre contract a company can buy, the underwater sounds of Dave Dobbyn melting through the speakerphone.

MBIE is currently calling for submissions on the future of the postal service. Maybe I’m hopelessly old fashioned, but I think we should do our best to protect these institutions. There’s no world in which we don’t need a post office. Whether you’re registering to vote, getting your passport renewed, sending out wedding invitations, or simply distributing your shoes around the country, we all rely on the postal service. There’s still no better feeling in the world than opening your letterbox to see a postcard from a friend in Italy or a handwritten letter from your grandmother.

Like our community mental health centres or rare native frogs, it’s the kind of thing it’s easy to take for granted, until it’s already gone.

Discussion about this post