State intelligence and enforcement abilities, as well as the legislation, need to be bolstered to deter the construction mafia.

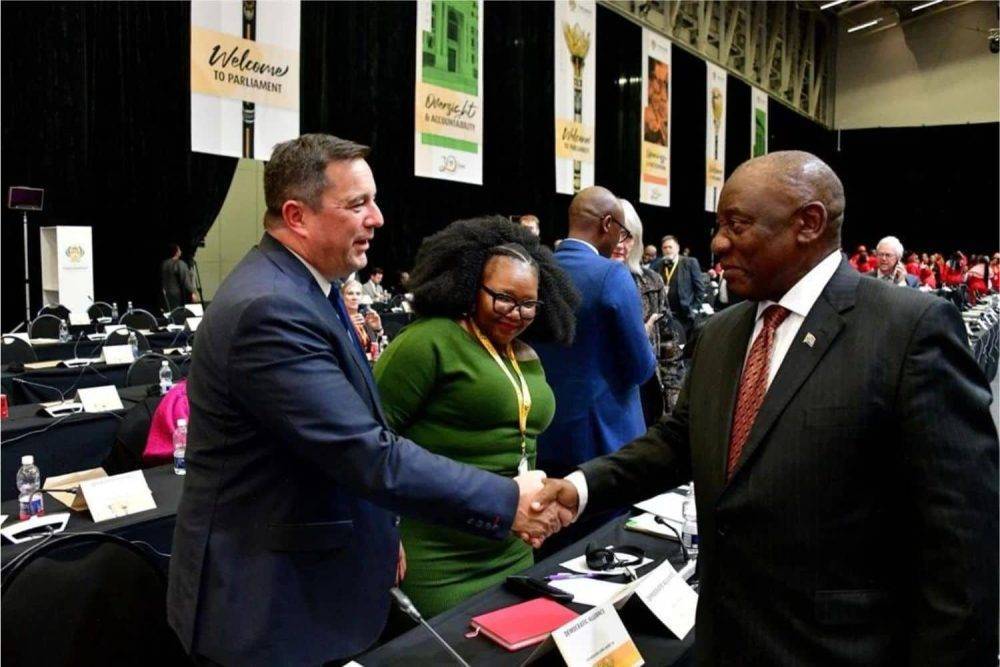

In recent times, the public works and infrastructure department, under the leadership of Minister Dean Macpherson, has been resolute in tackling extortion activities in the construction industry. This effort has been so pronounced that it can be viewed as Macpherson’s flagship initiative.

Macpherson, a member of the Democratic Alliance, has been collaborating closely with his counterpart in KwaZulu-Natal, Martin Meyer, who also belongs to the DA and serves as the MEC for public works in the province. Together, they appear to be championing the eradication of the construction mafia as not only a government policy but also a political priority.

I recently attended the National Construction Summit on Crime-Free Construction Sites hosted by the public works and infrastructure department, the South African Police Service, and the Construction Industry Development Board. This summit brought together a diverse range of stakeholders to share insights and strategies for tackling the pervasive issue of construction related extortion and crime.

The construction mafia’s existence, according to their political programme, appears to be linked to the ANC’s introduction of the 30% local procurement rule for subcontractors. The rule, as outlined in the Preferential Procurement Policy Framework Act, requires bidders seeking contracts worth R30 million or more to subcontract at least 30% of the contract value to Exempted Micro Enterprises, Qualifying Small Business Enterprises or small businesses as defined in the National Small Business Act. This provision aims to promote local economic development and empowerment.

The argument is that the 30% procurement rule has set a perilous precedent, allowing companies to exploit the policy and participate in extortionist activities. These companies demand that contractors allocate 30% of the work to them, even for projects unrelated to government procurement or those that don’t meet the R30 million threshold.

At the summit, Macpherson hinted that the government was looking into the 30% procurement rule, suggesting a potential push back. Such a move would align with the DA’s long-standing approach to dismantle black empowerment policies and adopt a more market-centric approach.

But it’s crucial to exercise caution when attempting to address complex, deeply ingrained issues. I remain unconvinced that merely repealing the 30% rule will mitigate the prevalence of extortionist activities in the industry. Extortion is a pervasive criminal phenomenon, with roots that extend far beyond a single policy provision. Moreover, abolishing the 30% rule would overlook the significant progress it has facilitated in terms of economic empowerment within the construction sector.

A more authentic and effective approach to addressing the issue of extortion in the construction industry would involve 1) improving state intelligence and enforcement capacities and 2) strengthening the legal frameworks to deter such activities and facilitate successful prosecutions. With regard to the former, the government ought to recognise that perpetrators of extortion on construction sites often operate within larger criminal syndicates, involving organised gangs, corrupt business forums, and government officials operating outside the law. To understand how these operations work, the government ought to invest in improving its intelligence capacities, which have been compromised over the years through the erosion of trust, corruption, and politicisation.

With regards to the latter, South Africa’s legal framework for prosecuting extortionists relies on the Prevention of Organised Crime Act (POCA), but its effectiveness is hindered by inadequate provisions. Notably, a 2022 report by Enact, in partnership with Interpol and Global Initiative against Transnational Organised Crime, revealed that despite the POCA’s existence, most organised criminal cases are still prosecuted under common law because of insufficient resources, poor intelligence and lack of specific provisions to target organised criminal leaders, coupled with weak sentencing guidelines. This renders the POCA ineffective in combating extortion.

In developing a more effective anti-extortionist method, South Africa could benefit from studying the United States government’s approach to dismantling the American Mafia. The introduction of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organisations (Rico) Act by the US government in the 1970s was pivotal, enabling prosecutors to target Mafia leaders and dismantle operations. Importantly, with FBI assistance, the Rico Act held accountable both direct perpetrators and facilitators, and lowered prosecution requirements. This approach effectively dismantled organised crime structures, leading to hundreds of successful prosecutions and contributing to the overall demise of the American Mafia.

Ultimately, to effectively combat the construction mafia, the state must prioritise substance over rhetoric, seeking genuine solutions rather than convenient political programmes. This requires a nuanced approach that addresses the root causes of the problem, rather than just its symptoms.

Siseko Maposa is the director of Surgetower Associates, a specialised management consultancy focused on corporate affairs and contributes articles to industry publications on infrastructure and construction matters.

Discussion about this post