This morning’s Gospel reading is Matthew 1:18–24:

This is how the birth of Jesus Christ came about. When his mother Mary was betrothed to Joseph, but before they lived together, she was found with child through the Holy Spirit. Joseph her husband, since he was a righteous man, yet unwilling to expose her to shame, decided to divorce her quietly. Such was his intention when, behold, the angel of the Lord appeared to him in a dream and said, “Joseph, son of David, do not be afraid to take Mary your wife into your home. For it is through the Holy Spirit that this child has been conceived in her. She will bear a son and you are to name him Jesus, because he will save his people from their sins.” All this took place to fulfill what the Lord had said through the prophet: Behold, the virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and they shall name him Emmanuel, which means “God is with us.” When Joseph awoke, he did as the angel of the Lord had commanded him and took his wife into his home.

What does it mean when we tell each other, “I’m with you”? Sometimes, it’s just a handy way to push people off. Yeah, I’m with you on that, buuuut … Usually, though, it’s a message of solidarity, although the depth of that varies, of course. I may be with you on, say, the clear and obvious truth that the Steelers are the greatest football team of all time, but not so much with you on the notion that Die Hard is a Christmas movie.

You with me on those? Hello? Is this mic on?

In other words, my “with you”-ness can be rather conditional. But what does it mean when the Lord promises that he is “with us”?

In both our reading from Isaiah and in Matthew’s Gospel, we hear that the Messiah is to be called “Emmanuel,” which means “God is with us.” Isaiah speaks of this in connection to the Lord’s invitation to King Ahaz of Judah to come back into cooperation with Him and to ask for a sign as a way to facilitate this. Ahaz refuses, however, and decides to ask the Assyrians for assistance against his enemies rather than the Lord, against earlier prophecies of Isaiah. The prophet then sends Ahaz a stern warning:

Then Isaiah said: Listen, O house of David! Is it not enough for you to weary people, must you also weary my God? Therefore the Lord himself will give you this sign: the virgin shall conceive, and bear a son, and shall name him Emmanuel.

The Assyrian alliance initially works in Ahaz’ favor, but in short order the Assyrians began treating Judah as a vassal state. Ahaz fell into idolatry as a result, even apparently sacrificing one or more of his sons to Moloch (2 Kings 16:3, 2 Chronicles 28:3). Rather than cooperate with the Lord and secure the blessings of His protection, Ahaz chose worldliness and personal power — and set in motion the decline that would result eventually in the Babylonian expulsion.

Ahaz clearly wasn’t with the Lord. The Lord desired to be with Ahaz, but Ahaz wouldn’t cooperate with the Lord’s will.

Many centuries later, Isaiah’s prophecies come to pass, only this time in a very literal sense. God is not only with us in Christ, He is one of us in Christ. This profound revelation forms one of the core mysteries of the Church, but also speaks to the depths to which God is truly with us. To show just how much He loves us and wants to save us from our own sin and concupiscence, He sends His only Son — His Word — into incarnate form as one of us to show us the way home to Him. And then, just to demonstrate how much He desires to allow us to cooperate with Him, Christ Emmanuel goes through a horrific death in order to prevail over it for our eternal benefit.

That is what is meant by “God is with us.”

And that prompts the question: are we with God? In a different part of Paul’s letter to the Romans that what we hear today in our second reading, the apostle famously asks, “If God is for us, who can be against us?”

The answer to that question is we ourselves.

How often do we make the same choices as Ahaz did? God reaches out to us, offers us His love and support, and yet we choose to rebuff Him and go our own way. How often do we treat the Lord not as a loving Father but as our rival? How much do we think of the Lord as a kind of spiritual police officer, looking to lock us up for every misstep, rather than our Savior who wishes us only the best for our eternal lives?

Every time we choose to reject the Lord and go in the way of sin, we are making the same error as Ahaz. Rather than cooperate with the Lord and prioritize Him over the fallen world, we immerse ourselves in materiality and lose our way. We may not sacrifice our children to Moloch, but we fall easily into idolatry and decline.

And yet, even through all of our sin and rebellion, God is still with us. He sent Jesus to us as His Emmanuel to demonstrate the complete depth and breadth of His love for us, in part as a sign to show how much He is “with us.” We can choose to cooperate with His will at any time, just as Ahaz could have done in that ancient spiritual crossroad. The Lord is our constant ally, our constant savior, our constant Father longing for our return to His side.

That is the meaning of Advent. It is not too late to repent and return to Him, and He sends His Son to guide us back. No matter how far we have wandered from Him, the Lord is still with us, waiting for the moment when we finally decide that we are with Him is as well.

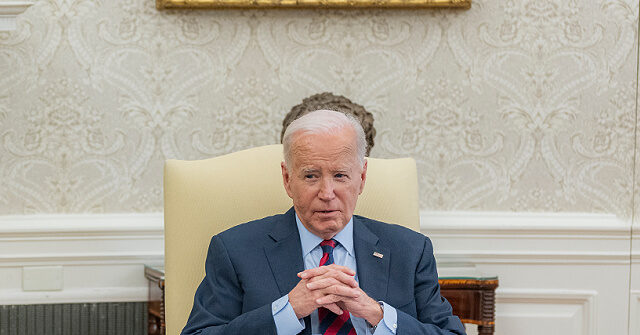

The front-page image is a detail from the fresco “Christ Emmanuel” at Teiul Domani by Alberto Giacometti, 1833. Via Wikimedia Commons.

“Sunday Reflection” is a regular feature, looking at the specific readings used in today’s Mass in Catholic parishes around the world. The reflection represents only my own point of view, intended to help prepare myself for the Lord’s day and perhaps spark a meaningful discussion. Previous Sunday Reflections from the main page can be found here.

Discussion about this post